ltered but Still Visible: Elements of Classical Origins in Sir Orfeo:

A typical medieval English audience would have been familiar with the classical Orpheus myth, says Kenneth R.R. Gros Louis in his essay examining the Orpheus traditions of the Middle Ages. They would have been exposed to it "primarily from Ovid's Metamorphoses , Virgil's Georgics , and Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy", although admittedly the Ovid was probably not as widely read as Ovide moralise, an anonymous compendium to Ovid which "twisted and distorted elements of the story to fit Christian doctrine and instruction" (Louis). This is not surprising, as even commentaries of the Bible were often read more than the Bible itself during this time period. In Ovid's version of the Orpheus myth, Eurydice is frolicking "o'er the flow'ry plain" when she is bitten by a snake and dies. She is taken to the underworld, and Orpheus mourns for her. He plays his harp so sweetly and sadly that even the king and queen of the underworld are moved with pity. They allow him to take Eurydice back to the world of the living, provided one thing: that he walks in front, leading her, and does not look back at her in any circumstances. Of course, as is typical in classical tragedy, he is overcome with worry and does look back, thereby losing is wife forever (Ovid).

The basic story in Sir Orfeo is strikingly similar. Heurodis, Orfeo's wife, is frolicking in a garden, falls asleep under grafted tree, and is stolen away by the King of Fairy. Sir Orfeo eventually plays his harp for the King of Fairy, gaining a boon which his uses to effect his wife's escape from the Fairy Kingdom. However, unlike the ultimately tragic Orpheus, Sir Orfeo does not lose his beloved forever, but is able to effect a successful rescue. After he returns home and regains his kingdom from his faithful steward, all is declared well and good. Is this "happy ending" more English that the tragic original? At the least, perhaps, it can be said to be more in keeping with the genre through which the story is being told, that is, the romantic lay. The lays of Marie de France, for example, are known for their happy endings, usually involving a marriage. This type of ending is generally considered characteristic of all medieval lays, both English and French, therefore the transformation from tragedy to comedy is almost necessary for the transmission from one genre (classical myth) to another (medieval lay), which in turn is an aspect of Anglicization.

What's in a Name?

Another immediately identifiable element that connects the classical Orpheus with the medieval Orfeo are the character names. The etymological connections between Orpheus/Orfeo and Heurodis/Eurydice are fairly obvious. It is interesting to note that especially in the case of Heurodis/Eurydice, the connection is far more audible than it is visual. This is most likely because of the highly oral nature of much of the transmission. The scribe who wrote Sir Orfeo likely felt the freedom to choose whatever spelling of names he liked, so long as the sound of the name stayed similar. Also, the spellings "Orfeo" and "Herodis" are also more anglicized than are "Orpheus" and "Eurydice", further familiarizing the heroes of the tale to their Middle English speaking/reading audience.

For more on audience and how they expirianced a text, see Jane Minogue's essay on audiences and readers.

Sir Orfeo's Parentage:

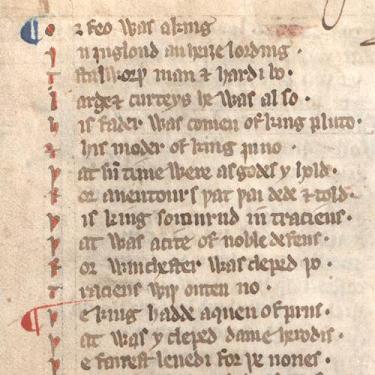

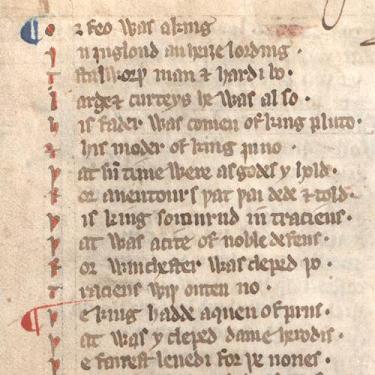

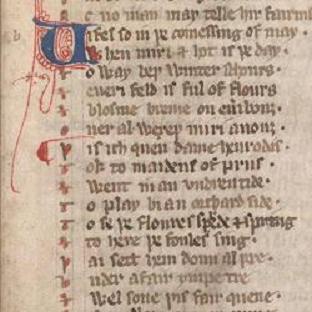

The beginning of Sir Orfeo contains an elaborate introduction to the hero that includes a discussion of his parentage. In fact, the passage that begins "Orfeo was a king" is the first line to appear in the Auchinleck Manuscript, as shown picture to the left. That the story would contain a 'genealogy' of this kind is wholly unsurprising in a narrative where establishing the main character's royal lineage is important. In order for the audience to accept that...

Orfeo was a king,

In Inglond an heighe lording, (l. 39-40)

(Sir Orfeo)

...some sort of proof must be offered that he is indeed royal. Thus the classical hero Orpheus, son of the Muse Calliope, (who may or may not have been readily known to the medieval audience) becomes associated with two more recognizable names: Juno and Pluto.

His fader was comen of King Pluto,

And his moder of King Juno,

That sum time were as godes yhold

For adventours that thai dede and told. (l. 43-46)

(Sir Orfeo)

Although Pluto and Juno were both easily recognizable as major gods in the classical pantheon, here in Sir Orfeo they are made mortal kings, in order to better suit them as ancestors for a Christian hero. The writer, however, seems aware that these names may be recognized as classical gods, and so he includes a 'disclaimer' of sorts: at least in the world of this story, Pluto and Juno are not gods, but they were once thought to be, due to their "adventours" and mighty deeds.

Location, Location, Location

In classical myth, Orpheus is often depicted as the king of Thrace. This element is included in Sir Orfeo, but like the hero's parentage it is tweaked slightly

This king sojournd in Traciens,

That was a cite of noble defens �

For Winchester was cleped tho

Traciens, withouten no. (l. 47-50)

(Sir Orfeo)

Orfeo still rules in Traciens (Thrace), but its location has been moved. "Traciens" is now Winchester, England. This relocation may be amusing at first glance, especially how the author emphasizes it, but it also shows an interesting reorientation of the classical location to a more familiar English location. The literary purpose of this relocation can only be guessed at, but it may have been to engender a sense of the familiar and further connect it to the Celtic mythic themes that continue throughout the work.

Further discussion on both the location passage and Orfeo's parentage can be found at my mini-web project Sir Orfeo: A Hero's Introduction.

Marie de France, as has been mentioned previously, is perhaps the most famous author of romantic lays. As is common with most romantic lays, "the lays of Marie de France usually describe some supernatural or fairy event or character" (Sanderson). Sir Orfeo may be by an unknown author, but it still shares this trait with the lays of Marie and as well as many other Breton lays.

The scene begins with Sir Orfeo's queen, Heurodis, going to play in the orchard with her maidens at "underentide", or late morning. Then Heurodis falls asleep beneath a "ympe-tre", which is "variously translated as "grafted tree," "orchard tree," and "apple tree"" (Anne Laskaya and Eve Salisbury, Sir Orfeo Notes). She is beneath this tree when she is visited by the Fairy King who steals her away.

Being stolen away to the fairy realm from underneath a tree, especially a grafted tree, has long been a part of Celtic Mythology. For example, Tam Lin, the Scots-Celtic hero, was kidnapped from under an apple tree. Because of the heavily Celtic history of the region of Brittany, it is not surprising that influences from Celtic myth should find their way into an Anglicization of a classical myth. After all, Celtic myth would be quite familiar to the Middle English speakers, as England was still deeply permeated with the mythological influence of the Celtic people.

Additionally, there is other imagery in this scene that may evoke familiarity with Celtic mythology through a connection with yet another mythology: Arthurian. One of the most stereotypically "English" of myths, the Arthurian myth has its roots deep in Welsh-Celtic mythology. According to Sanderson, Sir Orfeo contains elements of the Arthurian that a Middle English audience would identify and feel familiar with. He claims it is "significant that the action takes place in May. The May opening topos is a very familiar one in Middle English and French romances, both long and short. Adventures seem to befall characters in Spring after they have been cooped up inside their lodgings over Winter. [...] The queen going into her garden to play with her maidens in May would seem very familiar to the audience, they know they are going to hear a good Arthurian tale" (Sanderson).

Taylor points out that "In Sir Orfeo, the king is the finest of minstrels, just as Richard's popular sobriquet was, [...] Rex Menestrallus, "The Minstrel King." When he was duke of Aquitaine, he associated, as did Orfeo, with troubadours, and he indulged in poetic composition" (Taylor). Sir Orfeo is further anglicized by this connection to Richard the Lionheart, a familiar, beloved, and already legendary king for a Middle English audience. By connecting Orfeo's interests to a historical English king, the hero is given an immediacy and relevance he may not have otherwise had.

Additionally, one must note that Sir Orfeo's use of the harp is also deeply connected to that of the minstrels who would sing the Breton lays with which Sir Orfeo claims affiliation. This connection is further explored in Jane Minogue's essay Sir Orfeo and the Power of the Harp.

Return to Top

The Symbolic "Ympe" Tree

The Symbolic "Ympe" Tree