THE AUCHINLECK MANUSCRIPT

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Auchinleck manuscript, now the property of the National Library of Scotland (National Library of Scotland Advocates� MS 19.2.1) has been a valuable source for scholars of medieval literature since it was donated to the University in 1744 by Alexander Boswell (who was known as Lord Auchinleck, and was the father of James Boswell). This wonderfully varied collection of texts is prized for its wide range of material in various genres, giving scholars a unique look at the literary scope and interests of that time period. It is an anthology of the reading tastes, the language (including dialect differences), and preferred vernacular of the 14th century reading public, and it provides a wealth of insight into pre-Chaucerian Middle English poetry, of which there are few surviving texts.

The manuscript dates from the early 14th century (most likely between 1330-1340), and its early history is hazy: we know that Boswell had it in his possession in Scotland by 1740 (his signature can be found on a flyleaf with that date), and it is likely he acquired it in Scotland, since there is evidence it may have been in the possession of a professor at St Andrews University. Scholars do not know with certainty who may have owned the manuscript in the preceding centuries, though there are clues. Names are written in the margins of the manuscript, some from the 14th or 15th centuries, and also a group of eight names belonging to a Browne family (also dating from medieval times) that appear to have been written by the same hand; names dating from the 17th and 18th centuries can also be found (Auchinleck site).

The Auchinleck manuscript was produced in a time when fewer monasteries were active, and monastic book production had declined; a more commercial, lay milieu of production was growing, as were the number of literate people. Scholars who have studied the manuscript in depth surmise that it was produced for an affluent family, (probably not a noble one), and that it may have been read by Chaucer himself (though there is no hard evidence for it). The manuscript is unique in that it is the earliest example of a book produced in England that was lay (not liturgical), and made with commercial value in mind.

The range of genres contained in the Auchinleck includes verse romances, comic tales, instructional texts (of a moral tone), the lives of saints, poems, and religious verse texts. The romantic tales predominate (there are eighteen), and the manuscript is famous for its wide collection of what must have been the popular stories of the day, side by side with devotional texts. The romances are of differing types, as well: romances of English and French heroes; Arthurian romances, epic stories of bravery, and in particular, a type we will focus on in this site, the Breton lay, �Sir Orfeo,� which has a supernatural, mythic undertone (as does the romance, Reinbroun).

What is especially significant about the collection is that it is, essentially, all in English; it may be seen as the first (extant) example of a literary collection designed for an audience eager to read about its own history and origins, in its own language (not in Latin or French). The Auchinleck provides linguistic scholars with important insight into the dialects of 14th century Britain, as the scribes who produced the manuscript brought their individual dialects into their copying work (linguistic analysts have been able to differentiate between all of the scribes but Scribe 4, whose contribution was slight). According to the National Library�s Auchinleck website, the scribes� written work locates them linguistically as being from Middlesex, London, Essex, and the Gloucestershire/Worcestershire border area; the London scribes (1 and 3) provide a rich vein of study for linguists looking at the early stages of the development of the London dialect (Auchinleck site, 1).

In the following portion of our website, we will discuss the manuscript as a physical entity: how (and of what materials) it was made; how its physical elements have survived the centuries; its contents (and how they might have been planned), as well as various artistic elements that may be found within its folios. We will also look at some of the major theories and suppositions regarding the Auchinleck�s production process; there is some debate among scholars who have examined the work, and they have formed differing interpretations of the clues left by the medieval scribes and artists who brought the manuscript to fruition. Contents:

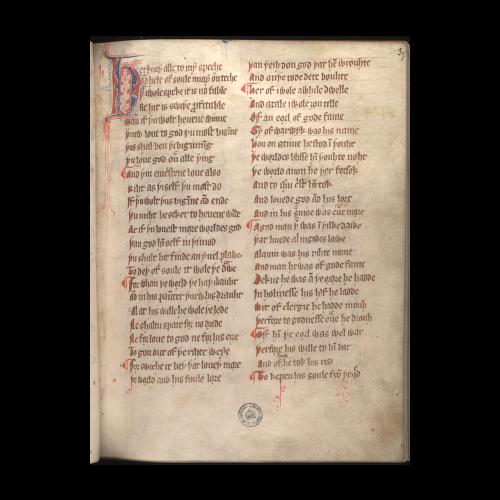

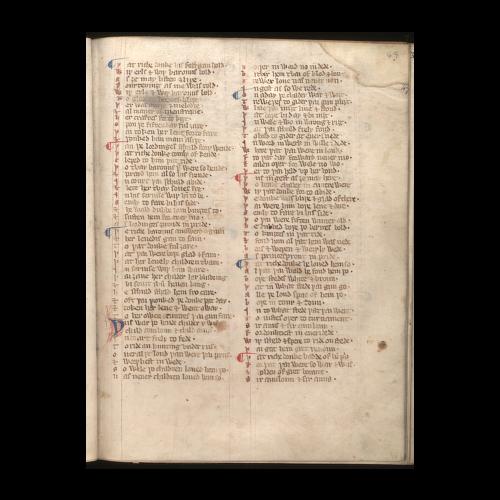

The manuscript contains 331 whole folios, and stubs of 14 others; there are 10 more folios (which at some time were detached from the manuscript) preserved in various libraries in Europe, and scholars believe at least 23 folios have been completely lost. The surviving folios are in good condition, and made of good quality vellum; in terms of size, the folios are now 250 x 190mm, but they have obviously been trimmed. Experts look to a fragment of another comparable text from that time, King Richard (owned by the University of London library) to see what the Auchinleck�s original size might have been. The folios are grouped into gatherings (also called �fascicles�) made up of �quires� of mostly 8 folios each (46 quires survive); there were probably more gatherings, it is not certain how many, but they are lost. Scholars know the position of these lost items by the item numbers that survive, and the missing texts appear to come from throughout the manuscript. Nothing is absolutely certain, however, as mistakes in numbering sometimes occurred.

Condition:

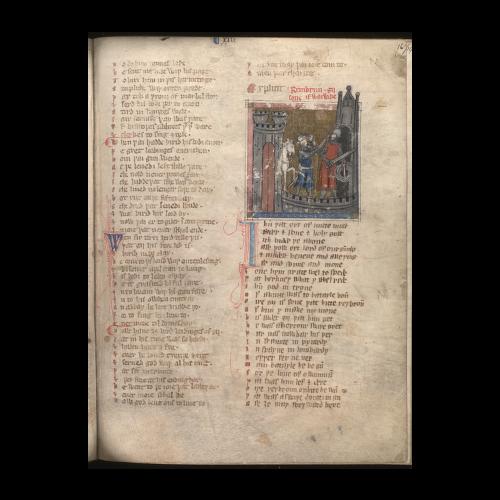

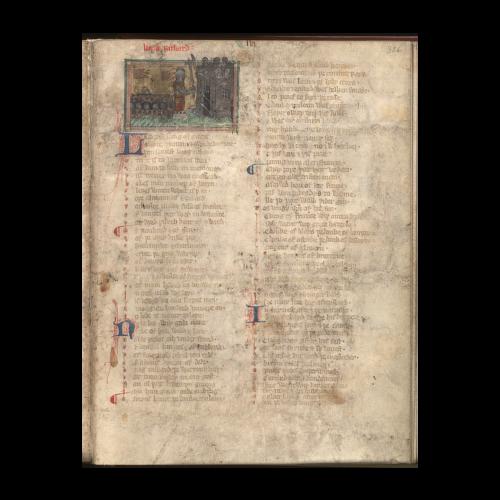

The most glaring aspect in terms of damage to the manuscript (beside the lost folios) is the loss of almost all of the illustrated miniatures that once decorated it. Only five of the original miniatures remain: the others were cut out by miniature hunters, who usually excised the small illustration from the page, but at times cut out the first leaf of a text (which had the miniature on it), leaving the stub of the page. As a result of the excision of the miniatures, the manuscript has lacunae throughout its pages (these are holes, or blank spaces in a text) that have been subsequently patched. Scholars imagine that the codex was probably quite attractive overall, though not sumptuous in design, as some other grander manuscripts from the period were.

The manuscript in the Library�s possession is in its third binding; the original binding can be detected from the sewing holes (it is not certain that this �original� one, however, is the very first binding, for pencil notes suggest that sometime in the 18th century, the folios were mixed out of order). The second binding was done in the 18th century by the Advocates� Library, and the present binding dates from 1971, when the volume was repaired. There are many aspects of the overall design of this manuscript which give it not only a commonality with other manuscripts of its type, but also its own particular look. The Auchinleck, because it is nearly complete and in such good condition, is a multi-faceted panoply of techniques and details that displays the talents and proclivities of the manuscript�s creators; through the individuality of the scribe/artists responsible for the manuscript, we get a sense of the world in which they lived. The richness of the detail and artwork open a door into the artistic perspectives being transmitted through texts of the time. More significantly, the variety (as well as the uniformity) of visual elements throughout the text allows us to more fully understand how the medieval reader (perhaps a neophyte to the very act of reading) may have experienced the manuscript. Every aspect of the materiality of the text would have resonated with (or surprised) a reader encountering it; we might keep in mind that the makers of such a visually rich tapestry of verse and image knew their audience, and were certainly striving to reach it with success.

(Note: Much of the information given here about the scribal elements in the manuscript comes from the excellent Auchinleck website, part of the National Library of Scotland). The Auchinleck Scribes and their Handwriting:

There is a sense of a �moment captured� about the manuscript, perhaps because the work of the six scribes who copied the collection has never been found elsewhere; we also do not know any of their names. They do not seem to have been stratified (in terms of ability or a hierarchy of rank), other than Scribe 1 doing the lion�s share of copying.

We see in the Auchinleck an interesting range of handwriting styles (�hands�) that lends the manuscript a sense of personality: for example, Scribe 4 (who copied only a list of names) has a formal, neatly rounded hand, while Scribe 5�s hand is �scratchy� and not easy to read clearly. Scribe 2 appears to have had trouble fitting his larger-sized writing into ruling that was drawn by Scribe 1; scholars have characterized Scribe 2�s hand as so �liturgical� in style as to locate him as coming from a monastic milieu (Auchinleck, 5). Ruling:

For the most part (the exception being Scribe 2, whose large hand mentioned above took up more space), the scribes wrote 44 lines per column; the majority of the texts are double-columned, written in varying shades of brown ink. But there was variation in the ruling, evidence of what Timothy Shonk terms, �the medieval tolerance for diversity� (Shonk, 78): for example, scribe 2 wrote the text, Speculum Gy de Warewyke, using only 27 lines to the column, not 44. Signatures:

The manuscript was produced by 6 scribes (all anonymous) whose work is only known from this collection. We get an idea of how the gatherings were ordered by the signatures of the scribes on their work, but no regular pattern of signatures is evident in the manuscript we have. Sometimes the scribe wrote letters on the right-hand side of the recto folios (in the lower margin), but not always: it doesn�t appear systematic. One finds the clearest signatures in quires 19 and 22, but even there some folios in the quires are missing part of the signature letter because of trimming. Catchwords:

One of the most important tasks for a manuscript editor was placing the gatherings in a coherent and sensible order; one of his tools for this was the use of catchwords. The catchwords link the end of one page to the next so that the compiler (or next scribe) knows how the gatherings link together. Given that so many scribes worked on the Auchinleck manuscript, Scribe 1, scholars agree, took great care to link his own work with other scribes� and their work with one another, making sure there were no loose ends or lost ends or beginnings. Not all of the catchwords have survived: some were lost to excised pages, and a few seem not to have been added. Scholars have identified thirty-six of the thirty-seven surviving catchwords as the work of Scribe 1. Item numbers:

The folios do not appear to have been numbered at the time the scribes were producing them, but we see item numbers throughout the manuscript: it is believed that Scribe 1 wrote them in after he had brought everyone�s work together, and after the manuscript had been decorated. The item numbers are in lower-case roman numerals, and appear on every recto (right side page), almost always in the center. If an item is numbered �iv,� for example, and has eight folios, each folio will show the �iv� at the top of all eight folios. More reason to surmise that item numbering occurred last is evidence that Scribe 1 moved a number off-center to accommodate a miniature; also that one of the item numbers covers a capital�s swirling adornment in the right column of script. Titles:

The titles appear to have been added once the manuscript was completed, using red ink; some scholars think that they were not part of the initial plan for the work, but were more of an afterthought. The titles are not always at the beginning of the item, but look as if they were squeezed into whatever space they�d fit (some being rather awkwardly placed). Scholars debate who was responsible for the titles; most believe Scribe 1 wrote them. Initial Capitals:

There is a consistency of style among the initials, perhaps suggesting that only one person was responsible for them. The scribes all preceded their two columns with a narrow column meant to set off the initial letter of each line; they thus left a place for the addition of the capitals by indenting their lines (generally two to four lines) and marking the space where the letter would go in brown ink. The initials are all large lombards done in blue ink with red ornamentation, most often with characteristic flourishes (and thin lines curling above and looping together), which scholars point to as possibly being the mark of one artisan (Shonk, 80). Paraphs:

It appears that at least three different rubricators (illustrators) worked on the manuscript�s paraphs (paragraph signs), which marked the beginning of a new section of verse: one can see the different styles of indicating marks they used. The artists involved may have all belonged to the same atelier, as they seem to have had access to gatherings communally, but made their own decision about what kind of paraph to add. They drew in these paraphs gathering by gathering: that is, if a poem spanned two different gatherings, the paraphs might be done by two different rubricators. Scribes knew to leave room for this decorative element, another sign that the Auchinleck�s planning was thorough. Scribes used red and blue primarily, and mistakes did sometimes occur; the rubricators did not always get the color right on a new page (Shonk, 79). Decoration of Miniatures:

It is a shame that so few (just five) of the original miniatures remain to be examined, for illustrations are one of a medieval text�s most interesting features, and certainly must have appealed to readers of the time. Nearly all of the items would have had a colorful miniature preceding the text (perhaps not the very short items), but these illuminations apparently were irresistible (and valuable) to scavengers, who cut around them in the text, leaving holes or merely the thin stub of the plundered folio. One may see the �ghosts� of many of these missing miniatures in the patched areas that precede thirteen of the poems, in addition to the stubs that remain where someone cut the whole page away (Shonk, 81). The five miniatures that remain (a link to view two of them follows their title) are at the start of The King of Tars; The Paternoster; Reinbroun (f.167rb); The Wench that Loved the King; and King Richard (f.326ra).

These five miniatures share a distinctive style, and are likely the work of one artist; but these images are also debated about by art historians. Some scholars say that these miniatures come out of one atelier (a group of artists/scribes working together and sharing technical ideas), perhaps the same one that made the beautiful Queen Mary Psalter. Others do not see the same level of quality in the Auchinleck as in the Queen Mary, and deem these miniatures mediocre or pedestrian (Auchinleck site). There has been much speculation and debate over the decades concerning just how this extraordinary work was produced, and because its origins are so undocumented, scholars have sifted through the extant manuscript to find clues about its creation. The scribes who produced the Auchinleck copied their work into quires, which were gathered into bundles (called �gatherings,� �booklets,� or �fascicles�). The 47 quires which survive for us to examine are comprised of 12 fascicles containing between 1 and 9 quires each. The quires have 8 folios each, except for quire 38 (which has 10). Bookmakers who produced manuscripts such as this one tended to place a major poem at the beginning of a new fascicle: examples of this in the Auchinleck include Guy of Warwick; Sir Tristrem; King Richard; and Beues of Hamtoun. Medieval scholar Timothy Shonk goes into great depth in his article, �A Study of the Auchinleck Manuscript: Bookmen and Bookmaking in the Early Fourteenth Century� discussing, primarily, the three major theories that have arisen concerning who was responsible for the Auchinleck�s production. Shonk cites the work of Laura Loomis, Pamela Robinson, and Doyle & Parkes, among others, and then weighs in with his own thoughts. It may be useful to lay out these theories Shonk discusses, to help us explore the possible scenarios surrounding the 14th century literary scene that gave birth to the Auchinleck: Loomis Theory of �a London Bookshop:�

It is scholar Laura Loomis�s belief that the Auchinleck was created in a �fascicular� fashion, springing out of an atelier-like bookmaking cell in London. Loomis (writing in the early 1940s) envisioned a group of �English authors� working in association with one another, and working at the behest of some wealthy patron. She based her theory on the close parallels that exist between the romances in the codex, and felt that this argued for a group of authors collaborating in a commercial enterprise, offering popular romance for sale to an eager public. Loomis also strongly suggested the possibility that Chaucer may not only have encountered the Auchinleck, but was greatly influenced in his own work by his reading of it (Shonk, 72). Robinson Theory of �Bookshop Production:� and the Doyle & Parkes Theory of Patron/Bookseller:

Pamela Robinson agrees in the main with Loomis�s theory of the �bookshop� center of production, but argues that evidence points to a more commercial, speculative motive behind it all. Robinson does not believe that a specific individual �ordered� the Auchinleck to be made for him, but that the collection came together �piecemeal;� other critics have agreed with Robinson�s scenario (Shonk, 72-73). Doyle and Parkes disagree with Loomis and Robinson, suggesting that the likely scenario was of a wealthy Patron going to a Bookdealer (an established commercial book business) and placing an order; the work was then contracted out to independent scribes (Shonk, 73). Shonk�s Theory:

Timothy Shonk takes the venerable Loomis theory, along with other influences, and comes up with his own take (in a related vein, scholar Fred Porcheddu, in an article on medieval bookmaking, casts doubt on Laura Loomis�s theories because, apparently, she never actually saw the manuscript itself) (Porcheddu, 473). Shonk believes that the work was indeed done in pieces by independent scribes, and in different locations (not in a workshop setting), and was done on a �bespoke� basis. Moreover, Scribe 1 did most of the work (roughly 70%) and most significantly, was the lynchpin of the enterprise. Scribe 1 acted as editor, liaison, and main scribe for the Auchinleck, and was the last person to work on the codex before it went to the binders. The six scribes followed a commonly agreed upon format, and they most likely worked on their own with no supervision. They did not, Shonk believes, share any of their work, and so did not collaborate in the classic understanding of the term. Each scribe copied at least one full work, and Scribe II copied three items. The scribes did, at times, share a gathering, but they never shared work on a single item. (Shonk, 74). Shonk argues that many elements of production suggest that the Auchinleck was carefully planned at its inception; for example, five of the seven major romances begin on a new gathering; economy was important, no doubt, as the book producers did not want to waste folios. So they ordered the items as best they could, using �filler� material to complete blank pages, so that the scribes might begin the major works on a new gathering. Although the scribes worked on their gatherings individually, they followed a mutually understood format (e.g., only three out of the forty-four items in the codex do not adhere to the double-column scheme). This demonstrates not �unity of production� (in a �workshop,� per se), but an overall roadmap for the codex; the scribes worked independently to solve problems occasioned by the �piecemeal� nature of the job, so that the finished product might cohere. Once all the pieces had been organized and the final marks added, Scribe 1 (Shonk believes) was the person who delivered the completed manuscript into its waiting buyer�s hands. (Shonk, 77). Summary

The production of the Auchinleck Manuscript has remained a matter for debate, but many clues point toward assumptions that one may confidently make: it was probably produced on a bespoke basis, and was not a bookshop product. The contents of the manuscript were most likely agreed upon before production started, and the Buyer may have made a special request for some of the major romances of the day, as well as religious pieces, lives of the saints, and general poems. The Buyer may not have really known exactly what he would get in toto, allowing the primary organizer (Scribe 1) some leeway in choosing content. The manuscript was certainly a product of six scribes, with Scribe 1 bearing the most significant responsibility for the successful production of this literary venture. There is a general consensus that the uniformity of decoration in the codex means that the decoration scheme was planned at the outset of production. Scribes would have known that there would be paraphs, initials, and miniatures added, so they were careful to leave marks and space for these elements. Even as plain and restrained in decoration as it was, producing the Auchinleck manuscript was likely an expensive endeavor; this suggests that an individual of means requested its manufacture (as a speculative work, it would have been a major economic gamble for any book producer). Though the scribes worked independently, they shared a stylistic and conceptual orientation that allowed them to weave their work together into a coherent whole. The beautiful St Albans Psalter (Hildesheim, Dombibliotheck MS St. Godehard 1), outstanding among medieval manuscripts for its excellent illuminations (especially the Alexis Master miniatures), is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of English Romanesque painting. It also contains the earliest surviving example of Old French literature, and thus is a highly significant text for studying the development of the French language. Scholars interpret the textual evidence as indicating that the manuscript was written at the Abbey of St Albans sometime around the year 1115; they especially point to the hand of one of its scribes (known as the Alexis Master): he was responsible for the Chanson of Alexis, and is generally regarded as being the same scribe who also produced the St Albans calendar, a work that was generated for the St Albans monastic community around the same time. The psalter�s illustrations and text have led scholars to believe that it was produced for a specific person: Christina of Markyate (born c.1096- died after 1155), a young woman who repudiated her family�s plans for her marriage and became an anchoress (and later, Prioress) at the Abbey of St Albans. Christina was given protection in the town of Markyate by the hermit Roger, an elderly recluse with whom she became very close; she subsequently formed an intimate (but apparently chaste) relationship with Abbot Geoffrey de Gorham, who had been a schoolmaster before becoming a monk. Geoffrey may have begun organizing the creation of the psalter for the use of his fellow St Albans monks (scholars believe the project began with the psalms), but it appears he came to fashion it as a gift for Christina (perhaps on the occasion of her taking her vows in 1131). Scholars have been drawn to the psalter for many reasons, one of which is its significance as an expression of a movement, growing at the time, toward a new kind of spirituality. The psalter (and the woman who inspired it) exemplifies what Magdalena Carrasco terms �the transformation of the Magdalen from a generalized allegorical type into an intimately personal model of the spiritual life� (Carrasco, 67). Carrasco suggests that the psalter might have been fashioned by Abbot Geoffrey as a way to guide Christina �in the behavior considered appropriate to her role and status� (Carrasco, 68). It is known that Christina took an active role in pursuing a kind of model spiritual life, as seen in many of the psalter�s illustrations, which act as a pictorial sequence, each miniature being a �visual preface to the psalms, which formed the basis of a life of prayer and meditation� (Carrasco, 71). Christina, as a �model� of a pious, reflective Christian, may have personified an evolutionary moment in the development of religious thought; what comes through to us as readers of the psalter is that she is a very real woman. After the death of her protector Geoffrey, Christina herself was all but forgotten, her memory deliberately swept under the rug by Geoffrey�s rivals at the Abbey, who abhorred what they saw as an illicit and sinful relationship between Christina and Geoffrey. It is assumed that the psalter remained at the priory of Markyate (near St Albans), and was at some time late in the Middle Ages taken to a Benedictine order at Lamspringe, England. The manuscript of the St Albans Psalter is owned by the parish of St. Godehard in Hildesheim, Germany. It is thought to have been brought there from England in 1803, but whether its owner was a private person or the church is unclear. Scholars agree that the book was still in England during the Reformation, as evidence shows that Henry VIII had the word �pape� erased from the calendar. Much of the following information about the physical properties and makeup of the psalter comes from the St Albans Psalter website. The St Albans Psalter is made up of five separate sections:

Click here for St Albans Psalter: Psalm 68 - A Discussion The psalter is comprised of a vellum book containing 418 pages, in 209 folios (it may be noted that the words �vellum� and �parchment� have been used interchangeably to describe the surface upon which texts were written as far back as the 15th century; though �vellum� does, technically, refer to the skin of a lamb, one really cannot identify the animal origin of a piece of parchment without a magnifying glass) (de Hamel, 8). A full leaf in the psalter measures 27.6 x 18.4 cm, but throughout the sections there is evidence that a great deal of trimming has taken place over time. The pages are numbered in Arabic numerals (1-417, i.e.) in the top right-hand corner of just the rectos (right side of the text); the miniatures are numbered individually, in a different (thus, later) hand. There is evidence on several pages that have illuminations on them of stitching (perforation marks); these were made by someone who chose carefully which images to sew fabric covers for (the covers acted as a �curtain� that both announced the image and protected it from wear). These images were probably considered of extraordinary importance to the work, and so worthy of special attention by the producers; at times, the stitching pricks through the text itself. One might infer that the images were privileged over the text, and the sewer desired to protect the illuminated initials foremost, even if it meant encroaching into the text itself. This is an example of how the materiality of a text (especially one whose origins are out of our empirical sphere of knowledge) can reveal meaning; what we may see and feel as we touch a manuscript is a kind of message sent from the hands that first formed it.

The manuscript was bound, according to medieval practice, using pigskin over wooden boards; it shows considerable wear, and was rebound sometime in the 1930s. The modern binders re-stitched the binding with needle and thread, so the original stitching holes are nearly invisible. The Christina Initial

Each of the historiated initials convey in images a key phrase from the psalm it belongs to. The �Christina initial� (on p.285), as it came to be known, is the initial for psalm 105, and it is apparent that it has been pasted into an empty space. The artistic techniques used in the initial (e.g., the softer, more delicate facial shading, and the unusually fluid fabric folds) mark it as being by an artist who did not do any other initial in the collection. The illustration shows Christina pleading before Christ for mercy (she has the monks of St Albans surrounding her), with Christ reaching out to her. There has been a lot of controversy and argument concerning the significance of the initial. Some argue that this page marks the time when Geoffrey, who had planned the manuscript, decided to tailor it for Christina specifically, giving the Psalter a whole new aura and purpose.

Scholars have noted the absence of the type of cloth cover mentioned above over the pasted Christina initial; if placing such a �curtain� over images marks them as especially cherished, it is significant that Christina�s initial had no such covering to protect it (i.e., no one sewed a cloth cover over that page). Perhaps, out of humble modesty, Christina did not want to call attention to her own page, or she wished it to blend into the work and not be exalted in any way.

The significant subject surrounding the Christina initial is how the manuscript may have been �feminized� by Abbot Geoffrey in honor of Christina, whom he greatly admired. The Calendar was not originally set to begin the Psalter (the illustration of St Alban was), but it was ultimately placed in that prominent position as her calendar; specially chosen miniatures were placed adjacent, that she might contemplate their scenes. Scholars note that these illustrations show a female figure in eighteen examples, lending them a personal, subjective significance for Christina. There is some debate surrounding the production process of the St Albans Psalter, as with many medieval texts, and scholar Kristine Haney has surveyed the major theories concerning its creation. Haney looks at a study by Pacht, Dodwell, and Wormald, which concluded that the Calendar, the Alexis quire, and the Psalms and Prayers were done by different scribes, with the Alexis quire being added on to an existing collection of texts. Most of the manuscript, however, was planned as a whole and completed relatively soon thereafter.

The common practice at that time (first half of 12th century) was to have a manuscript assigned to and done by one scribe. If a manuscript appeared to be done by more than one scribe, it is likely they collaborated with one another and consulted with whoever planned the codex. Scribes did share texts, copying portions of them and even correcting each other�s work.

But the St Albans Psalter appears to have been executed in a different pattern; a distinct plan seems to have been initiated, but portions were completed separately. Three main sections of the text stand independently of one another; there is no sign of interaction between scribes, nor any collaboration. Scribal differences are clearly detected, and the vellum and ruling techniques have noticeable divergences. What�s more, the work in these three sections differs from that in the �miniature� cycle. The scribe/artist who executed the Alexis quire (quire 2) is, as was noted above, commonly referred to as the �Alexis master,� for the artwork in this section of the psalter is of the highest quality. His scribal and illumination work, scholar Katherine Bateman notes, was known at the time as an �innovative model� for his artistic contemporaries (Bateman, 19). The Chanson of Alexis may have had particular resonance for Christina, and it was probably placed in such a prominent position in the psalter by Abbot Geoffrey, who knew her history. The tale concerns the nobleman Alexis, who, driven to serve God above all else, leaves his wife on their wedding night. Christina herself had eluded the clutches of her eager new husband on her own wedding night (she ultimately escaped to the safety of the monastery), and one might imagine that she took great solace from the text and illustrations in the work. The master scribe responsible for it has been the subject of much study and debate: although there is evidence the Alexis master worked with the artists who did the initials, scholars surmise that the other artists drew more from a common body of techniques than from each other.

According to Haney, who compares the work of the Alexis master to other manuscripts from the St Albans milieu, the design motifs the Alexis artist used in the Chanson relate not to those found in the initials, but to a common source between them. Aspects such as body proportions, poses by figures, and somewhat awkward-looking actions (added to the prominent stripes on the drapery) suggest style conventions found in other contemporaneous manuscripts (Haney cites the Prudentius manuscript, another text from the St Albans community, in particular). The design motifs appear to come out of a stock repertoire of techniques used at St Albans at the time.

The color palette used in the miniature cycle, moreover, is quite like that used in the initials, but it is not exactly like it. The paint that was used in the initials looks rubbed off in places, but the paint surface in the miniatures is in perfect condition. Also, the elaborate cobwebs and drapery folds seen in the miniatures are not evident in the initials. This, Haney argues, points to only a minor link between the miniature cycle and the initial cycle. The psalter artists seem less indebted to the Alexis Master than to a common pool of artistic techniques available to all of them (Haney, 5). There are, and have been, many other psalters in the world, but none of them has the uniqueness and resonance of the St Albans Psalter. Perhaps it is because it was completed with such care and dedication to the person of Christina of Markyate, but this psalter is suffused with an intimacy and personal aura that is still tangible to modern day readers. Created out of a tradition of illustration and writing that existed in England at the time Christina was alive, the psalter displays the wide range of artistic styles and motifs that were being exchanged within the monastic bookmaking community of the time. Unlike many other manuscripts of similar orientation, the St Albans Psalter was produced by bringing together the work of multiple copyists, who left their individual stamp on the quires making up the collection. The psalter was meant to be used everyday, and it contained the essential guidelines marking not only the days, but the prayers and reflections that were obviously so important to the community from which it sprang.

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION of the MANUSCRIPT

ELEMENTS of the MANUSCRIPT

THEORIES OF PRODUCTION

THE ST ALBANS PSALTER

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

ORGANIZATION of the MANUSCRIPT

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION of the MANUSCRIPT

Parts of the Manuscript:

The Calendar (quire 1) is written on a supple, cream-colored vellum of medium thickness whose hair side is suede-like in texture, and whose fleshy side is shiny; one may easily identify which side is which. The ruling is done in lead and orange crayon.

The forty Miniatures (quires 2-4) are painted on vellum in varying tones of deep cream to brown, a warmer hue than in the calendar. One may distinguish the flesh and hair sides easily; the flesh sides show marks from a knife and are smooth and shiny. Lead was used for the ruling, and the space is 18.1 x 14.1 cm.

The Alexis quire (quire 5) is written on vellum of deep cream; both hair and flesh sides are suede-like, and so thin as to be transparent in places. Ruling varies, and is sometimes ignored. Many pages show evidence of free-hand writing.

The psalter and prayers (quires 6-23) are written on white vellum; one may distinguish hair and flesh sides clearly. The illumination page of the Beatus Vir (p.72) is defined by light silver lines and orange-tinted lines marking out the figures. The �B� was made first, and then the capitals �EATUS VIR� (p.73) were added. The adjacent 56 lines of text are not ruled.

The Psalms, Canticles, Creeds, Litany and Prayers Pages (pp. 74-331) are quite lightly drawn, almost invisible at times (after p. 332, the hand is much heavier). The ruled space is 18 x 13.5 cm, 35 lines per page. From p. 411-414 the light ruling returns, with scoring nearly invisible.

Production marks:

PRODUCTION of the MANUSCRIPT

The Alexis Master and his Colleagues

Summary