MILITARY ORDER OF THE LOYAL LEGION

OF

THE UNITED STATES, MOLLUS

By: Gregg A. Mierka,

State Commander, RI MOLLUS (2003-2007)

and National MOLLUS Internet Committee Chair (2004)

READ BEFORE

THE RHODE ISLAND SOLDIERS

AND

SAILORS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

JUNE 16, 1880

Volume No. 2

N. BANGS WILLIAMS & CO., 1881

and the Battle of Salem Church, Chancellorsville Campaign, April 27 – May 4, 1863.

|

|

|

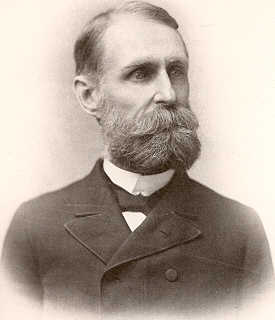

Col. Horatio Rogers

2nd Regiment, Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry

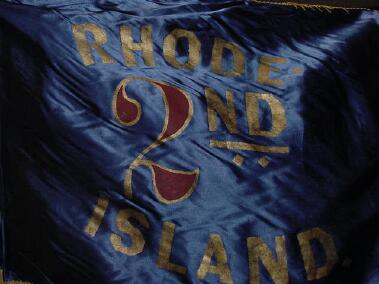

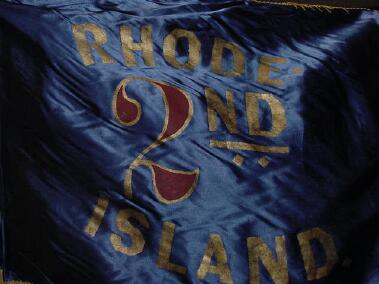

2nd R.I. Guide-on reproduce and hand painted by Gregory H. Payne

Hurled back from the heights of Fredericksburg on the memorable thirteenth of December, 1862, the Army of the Potomac, baffled and discomfited, had retired to the north side of the Rappahannock, and there sat down to watch its victorious foe. In those days of McClellan hero-worship, the Army of the Potomac was a dreary place for a general who proposed to advance boldly on the enemy, instead of cautiously proceeding with a spade in one hand and a pick-axe in the other, by a tardy system of parallels and circumvallations. General Burnside had realized it, as he was thwarted not less by his own generals than by the common enemy and, with his Ninth Corps, had withdrawn from Virginia to the south-west. General "Joe" Hooker had succeeded to that slaughter-house of the fame of hitherto successful generals — the Army of the Potomac, and all of us who belonged to that army were looking forward with different degrees of anticipation, to the approach of May, when the peculiar soil of Virginia would permit the transportation of artillery and of heavy trains.

The camp of the Second Rhode Island, surrounded by the other regiments of the Sixth Corps, was back of and a little below Falmouth, about two miles from the Rappahannock. It presented a rather picturesque appearance, located as it was on a gentle declivity, with its tents all banked or walled up for a couple of feet at least, while the left companies extended into a belt of woods through which the parade was reached. Back of all, the regimental headquarters, environed by an artificial evergreen hedge, opened into a little courtyard protected from the gaze of the enlisted men. Adjoining each tent, and rising two feet, more or less, above it, was a pile of split fagots laid cross-wise, out of which smoke curled, and which presented a most incendiary appearance, as it seemed as if very ample arrangements had been made to fire the whole camp. Notwithstanding the seeming incongruity, however, these apparently inflammable structures were the chimneys of the camp, and, plastered well inside with Virginia mud as they were, served their purpose admirably.

After the regiment was fairly settled in winter quarters, the weeks passed peaceably enough so far as the enemy were concerned, though not without interest to that particular organization. The monotony of camp life, with its drills and its gossip, was broken at intervals by a three days tour of picket. The regiment and its colonel did not always serve together, as a general officer had charge of the Sixth Corps line, while under him a colonel commanded the detail of each division. One of these occasions had an eventful, not to say serious, termination for the writer. It was in March and I was in charge of the picket line of the Third Division of the Sixth Corps, which was stretched along the bank of the Rappahannock below Falmouth, looking towards Fredericksburg. The tour passed off very pleasantly till the last night, when I was seized with malaria, previous attacks of which in South Carolina had threatened to prove fatal to me, and the next day I arrived in camp a sick man. After struggling with the disease for some days I was sent to Rhode Island by the medical director of the division, Dr. Carr, our regimental surgeon being absent on leave, and few believed that I would long survive. Home and home care had a most salutary effect, so, as April was rapidly passing and the papers were filled with rumors that the Army of the Potomac was to move at once as Hooker was impatient to strike the enemy, I started for the army before I had entirely recovered, despite the earnest protests and remonstrances of friends and family physician, fully determined that the Second Rhode Island should not go into action without its colonel at its head. Having telegraphed my coming to the regiment, I was met at the depot by quite a cavalcade of officers and escorted to headquarters, and never did the camp of the Second Rhode Island, which I had risked so much to reach, look more picturesque to me than on that April morning with the air full of rumors of an approaching campaign. As there was now no time to indulge in the "luxury of sickness", the excitement of preparation and the anticipation of coming events completed my cure. |

|

|

|

|

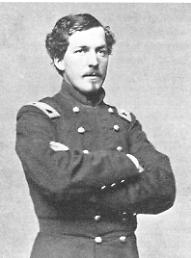

Dr. George W. Carr, Regimental Surgeon

2nd Regiment, Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry

Right Center photo: Col. Nelson Miles

Far Right & Left photos:

Confederate Dead and Destroyed Ordnance on Mary’s Heights

After Nelson Miles' Successful Attack at the 2nd Battle of Fredericksburg

The Army of the Potomac, however, did not move for several days after my return, and during that interval our brigade changed commanders, as General Devens, now the Attorney General of the United States, was promoted to a division in the Eleventh Corps. When he took his departure most of the mounted officers of the brigade, myself among the number, escorted him far on the way to his new command. He left us much to the regret of all who were serving under him, as he had deeply impressed us all with the nobleness of his character, and it is not too much to say that he will carry with him through life the affection and respect of every member of that brigade. Colonel Brown, of the Thirty-sixth New York, being the ranking officer, at once assumed command of the brigade, and after days of expectancy, days filled with all sorts of rumors and reports, the orders to move, so long and so anxiously waited for, came at last.

On Tuesday, April twenty-eighth, we broke camp, and all my soldier hearers will fully realize what that implies. Numerous odds and ends that collect in winter quarters, various appliances sent from home, superfluous clothing that overflows the narrow limits of an army valise, and a myriad of little nameless things that one does not wish to abandon, had been expressed to Washington or to Rhode Island at the earliest rumors of moving; but when the orders actually came, there was hurry and bustle, nevertheless, as tents had to be struck and packed, the separation had to be made of what was to go on the wagons, which no one knew when we were to see again, and what was to go on our own or on our servants' backs, or, if mounted officers, on our spare horses; and finally the men had to be got into line, a job by no means easy, as each had some last thing to do, which it seems to be an invariable rule with every old soldier not to do till the very last fraction of a second. At last when the regiment moved off', what a caravan it was. It almost makes one laugh to think of it. Every soldier had his gun and equipments, of course, but then, too, swinging on one side of him, he had a big haversack stuffed full of rations, as he was presumed to start with enough for eight days, which the Lord only knew how he was to carry. A canteen swung on his other side, while in a big roll, usually encircling him from the shoulder on one side to below the waist on the other, reminding one of Laocoon in the toils of the serpent, was his shelter tent, rubber and woolen blankets. Last but by no means least in this nomadic outfit, was the invariable tin cup holding a quart or possibly three pints, which was suspended from somewhere, just as it happened, and which served as a drinking cup and as a kettle to make coffee in. Following the regiment proper, came a gipsy looking band of servants loaded in most fantastic style with whatever could minister to the support or necessities of man, while the mounted officers' spare horses afforded as miscellaneous an appearance as could possibly greet the eye. Don Quixote's Rosinante and Sancho Panza and his ass, were aristocrats in appearance, compared with this motley crew. The Second Rhode Island, be it understood, was but a representative of every other regiment in the army. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

William Franklin; John Sedgwick; and Frank Wheaton

After the Second was formed it joined the rest of the brigade and then waited a long time for the orders to march. While it thus waited very diverse thoughts were running through the minds of the different members of that regiment. Not only had the Army of the Potomac changed leaders since it moved last, but the Second Rhode Island had changed commanders twice in the same period. The colonel was a new man to the regiment, and he and his field officers were all new to their present positions. When Colonel Wheaton became a brigadier in December, 1862, the lieutenant colonel and major were both, properly enough, advanced a grade; but the elevation of Chaplain Jameson to the majority proved a veritable apple of discord in the regiment, it being the general opinion that the chaplain who had started out ostensibly to serve his God, had ended by very effectually serving himself. The result of the embittered contention that ensued was an entire change of field officers, so, when the new colonel came from another organization, his coming was a disappointment to some and a pleasure to none, for while the officers with rare exceptions desired him to remain in command, it was only as a choice of evils. As we halted there patiently awaiting events, the regiment eyed its colonel to see what manner of man he was, and wondered whether, in the test by which he was about to be tried, he would be found wanting. The colonel, on the other hand, sat astride his horse coolly watching his officers and men, and on his part wondering whether they were ready to follow wherever he might dare to lead.

About three o'clock in the afternoon, after much halting and waiting, we proceeded down nearly to the bank of the Rappahannock, bivouacking for the night in a ravine concealed from the view of the enemy. Soon after daylight the next morning (Wednesday, April twenty-ninth), the regiment, accompanying the brigade, wound down the 'road nearest the river, to nearly opposite the ruins of the Bernard house, and there we lay all day Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and a part of Saturday. Our post was at the head of the pontoon bridge below Fredericksburg, where we acted as a sort of guard, with nothing to do but to watch and wait. The air was filled with rumors, and at last came printed orders from General Hooker, announcing, in rather grand eloquent terms, some early successes on first crossing the river.

The First, Third and Sixth Corps, under General Sedgwick, formed the left wing, but now the Third Corps was detached and sent to General Hooker, and then the First Corps, while the rest of us lay on the river bank and wondered. At night the sky was lurid with burning houses or material, and the heavens were literally lighted with the torch of war. The effect of all these rumors by day and of the lurid glare at night was to exhilarate some, and to rouse all manner of apprehensions in others. It certainly did not have an assuring effect upon weak nerves.

At length we crossed the river about half-past nine Saturday evening (May second), and as we did not reach Fredericksburg, but three miles distant, till the dawn of day, my hearers can readily imagine how much dreary halting and waiting we did. *We lay in the streets of Fredericksburg till eleven o'clock in the morning, when we were ordered up above the town to support our Rhode Island Battery B., Captain T. Fred Brown, of the Second Corps, which was playing on the enemy. The beauty of that scene I shall never forget. Battery B occupied the crest of a ridge, just below which in the rear was the Second Rhode Island in line of battle. Behind and below us on our left, was the town of Fredericksburg, seeming strangely out of place with its peaceful appearing mansions, from the door of one of which a refined looking elderly lady furtively peered at us as we passed. Before us and stretching far on either hand was an intervale through which we had an unobstructed view, while beyond that again, directly in our front and extending a long distance, was a ridge occupied by the rebels, and known as Marye's Heights. A creek ran between us and them, across which, so far as I could see, was a single road and bridge, and this was quite a little distance to our left though in plain sight. This road, where it crossed the bridge and extended through a cut up the hill on the other side, was known as "the slaughter-pen" in Burnside's attack the previous December, and well it deserved the name.*

The opposing batteries on the opposite ridges boomed away at one another vigorously, and while Captain Brown seemed to get his shell in among the rebels most successfully, they were not able to depress their guns sufficiently to harm him. Presently our Rhode Island Battery G, Captain George W. Adams, came thundering up alongside of Captain Brown, and went into action on his right. Soon after, a column of infantry poured out from Fredericksburg up through the slaughter-pen into the smoke of the rebel batteries and battalions that encircled them. Oh, how the cannon roared and the musketry rattled, and what a terrible suspense, though only for a moment. Then a loud cheer broke forth, and we could see the rebels breaking away in all directions from that road and getting to the rear. What was now to be done with the Second Rhode Island, was the question that presented itself to me. Evidently the batteries needed no further support, and as a constant stream of troops was pouring through the slaughter-pen and generals were scarce in my locality, I deemed it a safe rule of conduct, in the absence of orders, to always go for a rebel when I saw one, especially when he was trying to get away, so I started the old Second along. Our passage through the slaughter-pen, with its dead and dying scattered around, at once showed but too plainly how well it deserved its name; and after chasing rebels awhile on the extreme right, one of General Gibbon's aides ordered me to report back to my brigade, which I found on the plank road, a mile or so west of Marye's Heights.

We pushed westward along the plank road in the direction of Chancellorsville, and as our brigade formed the very rear of the Sixth Corps, the Second Rhode Island was the extreme rear regiment of the whole column. We went along peaceably enough for three or four miles, until we approached a little range of hills, when we halted and rebel shell roared uncomfortably over our heads. A shell bursting in the air directly over my head, was one of the things I could never take kindly to. Of all the fiendish, infernal, diabolical, devilish noises I ever heard, that is the worst. It seemed as if the devil must be in it, and was making a terrible racket in getting out. Though I am not an expert in that sort of thing, I always fancied it sounded as might a summons from hell, and, I am free to say, I never liked it. It was apparent that we had found obstacles, and that the rebels were in force in our front. We halted quite a little while for the regiments on our right to form in line of battle, and then we advanced again by the flank. At last we halted with the rest of our brigade, and one after another of our regiments was marched off. A battle was going on directly in our front, and it seemed as if the Sixth Corps was getting the worst of it. Finally, the Tenth Massachusetts, which was just ahead of us, started off, and the Second was left all alone on the plank road with directions, as it was in reserve, to wait for orders. It seemed to me like being on a sinking, burning ship, and told to stand quietly by until some one should come and tell me to do something for the common weal. It was clear that some of our troops were panic-stricken and that the line had given way somewhere. From the front and right of us a constant stream of men were thronging to the rear, with every indication of utter demoralization. As they went, they threw away their guns, and tore off their equipments and threw them away also. I had seen retreats, but I had never before seen the like of this. It seemed as if Bedlam had broken loose and chaos reigned supreme. Then a battery directly before us, and but a short distance off, limbered up in a trice and went to the rear as if it, too, had been smitten by a demon. I sat quietly on my horse and wondered where in the world were the orders I was told to wait for, and when, in the name of common sense, could reserves be more wanted than then. The steadiness with which the regiment had patiently halted on the very threshold of that battle-field, and witnessed the demoralizing scenes around it, was certainly very remarkable, and required more real nerve than actually participating in the battle itself; but we had not long to wait-Just after the battery thundered to the rear, a few dust-covered, bedraggled-looking horsemen came directly down the road, and not till the leader got close to me did I discover him to be General Newton, and as I was a comparatively new comer in the Army of the Potomac, it is doubtful if he recognized me. Drawing rein as he reached me, he inquired, "What regiment is this, Colonel?" "The Second Rhode Island, sir, "I replied, "directed to wait here for orders." "Colonel," said General Newton, in a deeply earnest voice, "form here and go to the right of that house, close to the woods"—indicating the direction with his hand—"we are being badly driven, hurry up and help them. "We had been marching up the road by the right flank and had simply halted a little before reaching the ridge on which the battle was raging. Forming a line on the right of the road, for the point indicated by General Newton was apparently on the extreme right of our line of battle, I advanced the regiment, wheeling gradually all the time to the left in the arc of a circle, so that we might come into action on a prolongation of our main formation of battle, as the, Union line was formed in an oblique direction to the road. |

|

|

|

Col. Horatio Rogers, Commander, 2nd R.I. Volunteer Infantry

Center: Capt. T. Fred Brown, Commander, Battery B, 1st Regiment R.I. Light Artillery

Right: Lt. Col. Samuel B. M. Read, 2nd in Command, 2nd R.I. Volunteers

As the Second came up, there was still a strong drift of affrighted men to the rear, and a broken battalion of Pennsylvania Dutchmen came pell-mell, as if they were going to run over us. I shall never fail to remember the advance of the Second Rhode Island. It surpassed its ordinary self, for it swept up, battalion front, despite its distracting surroundings, as steadily and well aligned as if on parade, and the broken Dutchmen, seeing but little chance of breaking through there, gave it a wide detour, assisted by some of our field officers, who, from the backs of their horses, with their heavy cavalry sabers, knocked some of the flying cowards head-over-heels. As we reached the ridge a wild scene unfolded itself, for it was apparent that the right of our first line of battle had been broken to pieces and hurled back in confusion, which explained the panic we had seen, and that the Second Brigade of the Third Division had been hastily pushed in to stop the advance of the victorious rebels. Fortunately, that brigade had been equal to the emergency. The formation of the ground was such that it would not admit a regiment in prolongation of the existing line of battle, and when the Second Rhode Island attempted to join on the Tenth Massachusetts, on the extreme right, all but the three left companies were thrown down hill in such a manner as not to be able to see the rebels at all. Accordingly, I ordered the regiment entirely clear of that hill, a little forward and to the right, across a brook and up another hill, where we unexpectedly found ourselves, owing to the peculiar angle of our main line of battle, much more detached from the rest of our troops and in their advance, than had been intended. But, whatever the colonel may have thought or intended, the boys as they now had plenty of rebs in their immediate front, improved the opportunity to relieve their long pent up nerves and to blaze away as fast as they knew how. The three left companies had been too busy firing to heed the orders to advance with the rest of the regiment, and hence I had but the seven right companies, with the lieutenant-colonel, with me, the major with the three left companies having remained on the right of the Tenth Massachusetts, actively engaged in emptying the barrels of their muskets at the rebels. A portion of the Fifteenth New Jersey, which had formed a part of the first line of battle, came up and were formed on our right.

The scene then was a noticeable one. On our left, a little distance off, was our main line of battle opposed to the rebel lice; then, with quite a gap between, came the Second Rhode Island, off beyond both lines of battle but advanced far beyond a prolongation of the Union line, and opposite the Second was a broken mass of rebels that had stretched out over the space between the left of their present line and the right of our original or shattered line. The rebs in our front retreated before us, and it was evident that our movement was neither relished nor understood. Way across an open field, well to our right and in front of us, an American flag fluttered in the edge of some woods, and raised the suspicion that the rebels were playing another Fair Oaks trick by attempting to deceive us with false colors. It was, however, in the precise direction of our first line of battle, and about where its right undoubtedly rested. Presently a first lieutenant came running across the field, making a wide circuit to avoid the rebs, and, greatly excited, rushed breathless up to me, announcing himself as the adjutant of a New Jersey regiment in the woods there where the American colors were, stating that it formed the right of the first line of battle, that the rest of the line having been broken had left it in the woods heavily engaged, nearly surrounded and almost out of ammunition, and begging me in the most earnest terms to go over and help them out. Here was a quandary, indeed. Already I was far in advance of our main line, and an enigma to the rebels and probably a source of anxiety to our own people. However, general officers were not around, and General Newton had given me a sort of roving commission; at least, I proposed to treat it so, and here was a case that demanded action. The prompt reply to the distressed lieutenant was "I will go", but the next question was how to go, for it is no easy job to stop a line of battle when firing and advance it in the nature of a charge. Though I was satisfied the broken bodies of rebs in front of us would retreat before a resolute advance, yet in the din of battle the human voice cannot be heard ten feet, and mere verbal orders would be of little account to affect the desired purpose.

When a captain in the Third Rhode Island, I had seen the difficulty of charging with a line of battle, at Secessionville in South Carolina, though gallantly accomplished at last by Colonel Edwin Metcalf, then a major in command of a battalion. An infantry colonel's position, according to tactics, is thirty-five paces back of the file-closers in rear of the center of his line; but, if I had proposed to myself to occupy that position, I might, about as well have been in Rhode Island for all the good I could have done. So, when an advance was determined on, I directed Lieutenant Colonel Read to go along the front of the regiment from the right, while I did the same thing on the left, and knock up the men's pieces with his sword, at the same time ordering the officers to aid in stopping the firing and in advancing the line, by taking positions in front of their men, just as they would on dress parade, when ranks were opened, and follow the colonel. The excited nerves of the men would induce them to stop and fire, unless by so doing they would shoot their officers, but they would follow without a shot if their officers only led, rapidity of motion being essential to success. It was a novel formation for an infantry advance, but it answered the purpose, as we reached the woods quickly, and the rebels prudently got out of the way. It was a sore enigma to the left of the rebel line of battle, who did not understand it at all, as it might be some sort of a flank movement, or something else, but what it was they certainly did not know. Our own people were equally at a loss to understand it, and Colonel Eustis, of the Tenth Massachusetts, who, when Colonel Brown of the Thirty-sixth New York was shot, succeeded to the command of our brigade, exclaimed—"Oh, my God! There goes Colonel Rogers and the Second Rhode Island without any support". Never was a man more glad to see another than was that New Jersey colonel to see that Rhode Island one. He said his ammunition was about exhausted, and he wished to know how he should get out of there. So the Second formed directly behind him, and his regiment fell through our ranks.

The next thing was to get out myself, for the fire was withering, the rebels being at close musket shot and having a wicker fence for a partial protection. Our boys lay as flat to mother earth as they could get and fire, and fearful that the rebels would make a rush when we retreated, I sent Lieutenant-Colonel Read back for my three left companies, and also begged him to get another regiment if he could; and I added this inane injunction: "Now, Read, be careful, and don't be such a fool as to get shot". It is true my major was not with me, and I was just sending off my lieutenant-colonel, when, if anything happened to me, his services would be needed in the woods, but I had not the slightest fear of being shot, and I felt that my captains were all capable. I really only expected to get my three left companies, and wished some one to go who would pilot them where we were and who could speak, as it were, with authority. Meanwhile, the rebs and the Second were firing away at each other in the liveliest possible manner, and I verily believe that some of the boys fancied they understood what the Prophet Isaiah meant when he said: "Hell hath enlarged herself and opened her mouth without measure", and that they thought they were then in the enlargement referred to. It was hardly to be expected that men would stand under such a withering fire without recoiling a little, so from time to time the flags would be carried forward, and right gallantly would the men rally upon them and go at it again. At last, after half an hour, or perhaps more, and it certainly seemed longer, I ordered the regiment to fall back steadily, believing that the lieutenant-colonel had had time to bring us relief if he was able to do it. As we got to the edge of the woods we gave the rebs three parting cheers, and there we found our three left companies and the Tenth Massachusetts, under Colonel Eustis. The battle was over and the rebs had fallen back, so that the field was much clearer than when we came across. Colonel Eustis ordered the Second to the rear without delay, and himself set the example by marching off the Tenth Massachusetts; but I could not bear to leave our brave wounded comrades in the woods without an effort to recover them, and as the rebs had shown no disposition to pursue us, I ordered each captain to send ten men under a sergeant into the woods and bring off all the wounded they could find, and waited for them to do it. Then we followed the Tenth Massachusetts, at some distance, back across the field to the house whence we started. Ammunition was served to us on the field, and we lay there in the front line of battle with one eye open the entire night, but all was quiet.

The next morning we had some mournful duties to perform, and we commenced the day with burying two first sergeants who had fallen the day before, and whom we laid tenderly away under a large tree with their blankets as their winding-sheets. Then came calling the roll to make up the casualty list, and no one present will ever forget it. We lay there in line of battle, ready for the enemy, and each company was called in presence of the regiment. About a hundred were either killed or wounded, but as some had only slight hurts the list was reduced to eighty-three out of less than five hundred taken into action. As each name was called, the bearer, if present, answered, "Here", and if he was hurt he so reported and his case was looked into. If, however, there was no response, inquiry was made as to the reason why, and the report of an eyewitness would furnish the sad evidence of death or conveyance to the hospital. But some names were called which were not answered to, and about the bearers of which no testimony could be elicited. Of some of the poor boys no intelligence has been gained from that day to this. The simple recital would be by one or another of his comrades—"I saw him go into the woods, sir, with his company". We all drew the grim deduction that he never came out. |

|

|

|

|

|

Painting of Howard’s Union XI Corps Being Routed by Jackson's assault on the extreme Union right flank

Alfred Waud's Drawing of Jackson’s Charge Against Howard’s Corps

Bottom Images Left to Right:

Major General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the 11th Corps

and the focus of Jackson's attack

Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee & Stonewall Jackson,

their last fateful gathering the night before the battle to discus the planning of Jackson's assault on Howard

Third Corps Commander Major General Daniel Sickles

who made Howard's position worse by attacking Jackson's rear supply,

putting Jackson and more than half of Lee's army completely behind the Union Lines,

isolating Howard to face the full brunt of Jackson's surprise attack.

All that day we lay in line of battle by the house, and the air was heavy with rumor. Stonewall Jackson had swept around our left flank and captured Fredericksburg; General Hooker was in full retreat, and some thought the Sixth Corps' prospect of going to Richmond was remarkably good, but not with arms in their hands. Army croakers are a doleful set, and the corps was full of them. Early in the afternoon heavy firing was heard off to our right, as we were, so to speak, in a bag, and the rebels were trying to close the mouth of it, while General Sedgwick sought to keep it open and preserve a passage to Banks Ford, several miles up the river, where a pontoon bridge was laid across the Rappahannock, the bridges at and below Fredericksburg having been severed at the time of Stonewall Jackson's raid. Every one looked sober and felt as he looked. Our sole hope of salvation lay in preserving communication with Banks Ford, which was disputed the whole afternoon. After nightfall troops were passing us continually, going from the left to the extreme right, up the river in retreat to Banks Ford. As the Second Rhode Island was on the right of the line, it was the last to start, and it seemed to some as if it never would start. Finally, when the time came to go, no one stopped to question the reason why, but went at once. The march to Banks Ford was a race of diligence between us and the rebs, and the rebel column marched along parallel with us. At times, it seemed to me, it was not more than a hundred yards distant, but we were nearest the river, and when the rebs found that they could not head us off, they began to shell us. We got safely over the Rappahannock, and every one breathed easier. Not far from three o'clock in the morning, we stumbled into bivouac as well as we could, a mile or two from the river bank, and slept till daylight.

Tuesday was hot and sultry, as the Second had ample opportunity to find out, as about noon the regiment was ordered down to Banks Ford to guard the pontoons, some of which had been hauled up on the river bank—a service the general informed me was of the utmost importance and required unceasing vigilance. The hot Virginia sun wilted several of the officers and men on the march, and the rebels, seeing us approach, burst shell over us till we reached the cover of the woods skirting the river. The pontoons had been placed in the narrowest part of the stream, and it seemed as if the rebel pickets on the other bank were only a few hundred feet away. Indeed, we were so near that we could distinguish the features of several rebel officers who came down to the river brink to look across, but though we were so near, neither offered to molest the other. There we lay for several days, and at times it rained in torrents, so we had to serve as clothes-horses a part of the time to dry our wet garments on, as we had nothing with us but what we stood in. Barely have I ever had a heavier burden of responsibility resting upon me than those pontoons, as my orders were, if the enemy attempted to cross, to fight to the last man, and the rebels were so near and flushed with victory, and it seemed so easy for them to cross, that the orders appeared terribly significant.

At last the Second Rhode Island was relieved, and marched back nearly to its old location below Falmouth, after an absence from it of eleven days, in which we had not taken off our clothes, and for more than a week. I did not even take off my boots. The generals were unanimous in the expression that the Second Rhode Island had done its whole duty; its old commander, General Wheaton, said it had added another bright leaf to its already brilliant record; and the General Assembly of Rhode Island tendered it a vote of thanks for its gallant conduct. Thereafter neither regiment nor colonel wasted any more time in wondering about the other, and thenceforward the latter ceased to be regarded as a stranger, and was looked upon as a fully initiated Second Rhode Islander. |

*This battery belonged to General Gibbon's division of the Second Corps. General Sedgwick in his examination before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, says: "General Gibbon's division belonged to the Second Corps, but was ordered to cross and report to me at Fredericksburg." |

THE RHODE ISLAND SOLDIERS AND SAILORS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

JUNE SIXTEENTH EIGHTEEN EITHTY

Postscript: President Abraham Lincoln was for a time somewhat distracted from the underlying problems of the Union Army of the Potomac due to his emphasis on issuing his Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863. General William B. Franklin (of Pennsylvania), descendant of Benjamin Franklin, highly influential and powerful in Congress, was backing his friend General “Fighting Joe” Hooker (of Massachusetts) to replace General McClellan as army commander in the final months of 1862, after the Battle of Antietam. When Lincoln selected Ambrose E. Burnside (of Rhode Island), the next and most capable senior officer in the Army of the Potomac, to replace McClellan instead of Hooker, both men fostered and encouraged a political conspiracy to undermine Burnside in the army and in Congress. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton warned Lincoln about what he said was, “out and out gross insubordination against, the President, the War Department and General Burnside” (their army commander), and wanted both Franklin and Hooker completely relieved from military service. After the 1st Battle of Fredericksburg December 11 - 14, 1862, the Union Army of the Potomac was in disarray due to increased political in-fighting between the Generals of the Army of the Potomac. In the end, due only to political pressure from Congress, against his better judgement, Lincoln had to act by replacing Burnside with Hooker, but he quickly gave Burnside another command to capture East Tennessee. After the 1st Battle of Fredericksburg and prior to his departure, Burnside developed 2 strategies for getting across the Rappahannock River to meet Lee on common ground. As winter of 1863 seemed to break Burnside first tried a flanking move down stream to the east, which due to unusually heavy rains was called the “Mud March”. His second strategy was to move the Army of the Potomac West across to Rappahannock and the Rapidan Rivers to swing around Lee’s rear at Fredericksburg. In the spring of 1864, a year later, Grant would try the same tactic. Hooker ended up using this strategy as well in April 1863 after his promotion to command the Army of the Potomac. Hooker proclaimed, “I have the finest army on the planet”. “If the enemy does not run, God help them”. Lincoln said, “That is the most depressing thing about Hooker”. “The hen is the wisest of all the animal creation, because she never cackles until after the egg is laid”. After the disaster at the Battle of Chancellorsville Hooker himself said, “I just lost confidence in Fighting Joe”. The battles of the entire Chancellorsville Campaign became Lee’s greatest military campaign victory, not Hooker's, but Lee's most costly. Lee’s most serious loss was his closest and most trusted General Stonewall Jackson, who was killed. The 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment was part of Justice M. Brown's Brigade, Frank Wheaton's Division, John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps. It participated in the second phase of Hooker's plan of attack. General Sedgwick and his 6th Corps was ordered to create a diversion in front of Lee at Frederickburg so Hooker could get around Lee’s left flank to the west. At first the plan envisioned by Burnside and put in motion by Hooker worked perfect and completely caught Lee off guard. But, for some unknown reason Hooker pulled back to the Chancellorsville area near the Wilderness to try to defend an untenable position and allowed Lee the time he needed to react. When Lee moved west to meet the threat of Hooker, Sedgwick moved against the Confederates who were left behind by Lee to defend Fredericksburg. Once Lee put Hooker in to a retreat at Chancellorsville west of Fredericksburg, he turned back and headed east to defeat Sedgwick, moving on his rear at Salem Church, west of Fredericksburg. Along the Rappahannock in the spring of 1863, Lee defeated Hooker’s entire Union Army, a force about 4 times his size, and his other trusted General, James Longstreet, previously sent south, defeated the Union attempt to take Richmond by way of the James River—a clean sweep, that emboldened the Confederacy to invade Pennsylvania later that summer. After the Battle of Gettysburg in July, Rogers, due to his illness with malaria, was forced to resign his officer’s commission and return to his home in Providence, Rhode Island to convalesce. Col. Samuel B. M. Read was promoted Rogers' successor to command the 2nd R.I. Volunteers until his enlistment ended at the siege of Petersburg, VA., under General Grant in 1864. Elisha Hunt Rhodes succeeded Read as commander of the regiment to the end of the war. Rogers was selected to replace Chaplain (Col.) Thorndike C. Jameson, who briefly followed Frank Wheaton and Nelson Viall. They, unlike Jameson, held great respect by the men of the Second. Rogers became the unit’s 5th commander. Rogers rose to prominence after displaying great tenacity commanding a company of the 3rd R.I. Heavy Artillery during the Battle of Sessionville, (James Island, Charleston, South Carolina) early in the war. Rhode Island Governor Smith appointed Rogers to replace Jameson to try to improve unit moral. Rogers quickly proved himself to be a steady and courageous leader to the men of the 2nd during the Chancellorsville Campaign. The 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry fought under the 6th Corps, Army of the Potomac throughout most of the war and to its end. It was engaged in more battles than any other Rhode Island unit in the Civil War. Rogers was commended for his actions during the Chancellorsville Campaign by Generals Hooker, Sedgwick and Wheaton. After the Civil War, Col. Horatio Rogers, Second Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry Regiment, became Post Commander of R.I. Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Slocum Post No. 10. In 1869, he became the 3rd elected State or RI GAR Department Commander. Rogers was also a member of the Massachusetts MOLLUS Commandery. His MOLLUS ID # was 05369. He eventually died from the effects of the malaria he struggled with for years after the war.—GAM |

For More Information About The 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, Click HERE

To View The 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, Macro Media Slide Memorial Click HERE

To Read More About The History Of The 2nd Rhode Island Volunteer Infantry, Click HERE

BACK to Table of Contents War Papers Volume #2HERE

BACK to War Papers Index ALL VolumesHERE

Visit the Main Homepage of the

Rhode Island Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

Visit the Main Homepage of the

Rhode Island Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War, Elisha Dyer Camp No. 7

{ Return To The Top of This Page }

MOLLUS Internet Published War Papers

| ________________________________

Source: Copyright© 2004, Gregg A. Mierka, Rhode Island Commandery, Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

|

Get your own Free Home Page

Get your own Free Home Page