The Historical Significance of

Micro-parasitic Infection as Detailed in William McNeal’s Plagues and People

by: Giovanni JRC

William

McNeal, author of the book called Plagues

and People, devised a persuasive argument as he contended that the

microscopic world of single and multi-celled organisms played, and still

continue to play, a significant part in human history. Because the study of microbes and their

effects on humanity are often limited to biological and anthropological

inquiries, this notion is a relatively new aspect in the investigation of

historical events. Nonetheless, historians

did record numerous accounts of illnesses and diseases that swept entire

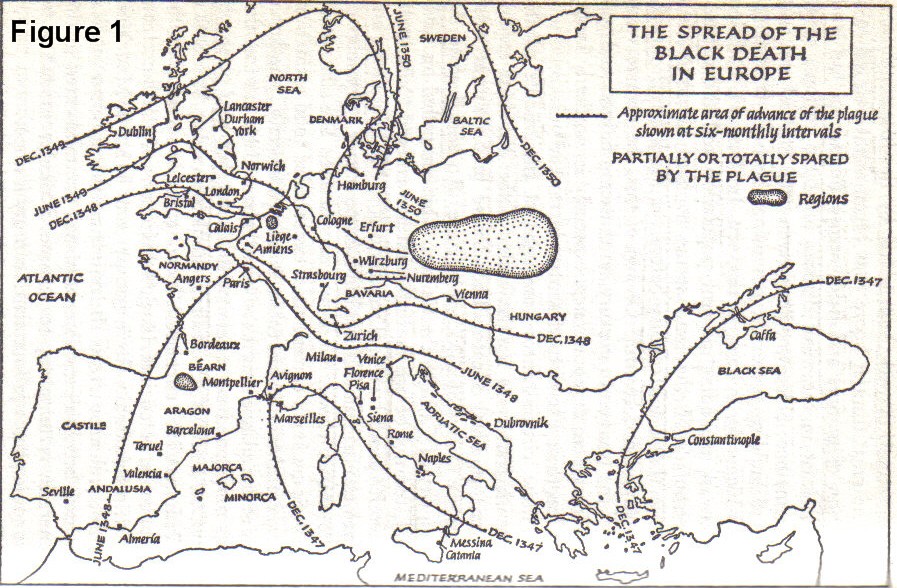

nations such as the Black Death in

He achieved this by first outlining a pattern of interface between early humans and the microscopic world around them. He stated that early in history, humans were subject to the limitations and boundaries the micro-parasites created. Micro-parasites, which McNeal defined as, “tiny organisms—viruses, bacteria, or multi-celled creatures as the case may be—that find a source of food in human tissues suitable for their own vital processes,[1]” essentially “preyed” on their human hosts and since early humanity’s exposure to these organisms were limited, their susceptibility to infection and death was

very high. Nonetheless, prolonged contact with microbes

within their area of habitation caused the early humans’ physiologies to adjust

to the organisms. McNeal emphasized this

by stating, “Prolonged contact between human host and infectious disease

creates a pattern of mutual adaptation which allows both to survive.[2]” Thus, a symbiotic relationship is achieved

since the parasites can live within their hosts, and humans benefit from the

immunity they gained against surrounding microorganisms. However, because of the numerous types of

thriving microorganisms, single and multi-celled, which spread throughout the

world. Early humans were only able to

maintain immunity against parasites within their region of habitation. Thus, venturing out of their immediate

territory exposed them to new forms of possibly fatal diseases.[3] An example of which was the “sleeping

sickness” of the African savannah.

Non-fatal to their antelope hosts, the microorganism called trypanosome

inhabited a small region of the savannah where tsetse flies abound. Because these tsetse flies were the main modes

of transmission of this disease, early humans kept their distance from these

areas were previous experiences dictated that if they ventured forth, they

would contract the “sleeping sickness” (since they did not know it was the

flies that caused the deaths).

Incidentally, this also kept the human hunters from preying on the

antelopes thus they are still abundant in the savannah to this day.[4] This example demonstrates McNeal’s idea that

micro-parasites limited the areas in which humans can live and where they can

migrate to. He, however, did not mention

that although the climates in

According to McNeal, another way these lethal microbes limited the spread of humans throughout various continents was by the way they regulated population growth. Because multi-cellular organisms did not elicit an immune response from the body, and medical knowledge to combat such illnesses was nonexistent, humans had always been susceptible to such infections. Thus, when populations increased, which were conducive to the spread of multi-celled parasitic infections, death from microbial diseases ensued.[5] Through this process, the increase in human population was negated by these hazards. Due to this, the early humans had no need to migrate and spread to other available land masses because their numbers were too few to begin with.

Despite the overwhelming effects of these organisms, humans were able to adapt as they devised social restrictions to evade these unknown assailants. For example, because of the apparently mysterious sources of these sicknesses, early man associated these hazards with religion and spirituality. Because of this, they created religious taboos to prevent such infections. Examples of which are the Jewish and Moslem prohibitions regarding the consumption of pork. McNeal stated, “This appears inexplicable until one realizes that hogs were scavengers in Near Eastern villages and quite capable of eating human feces and other ‘unclean’ material. If eaten without the most thorough cooking, their flesh was easily capable of transferring a number of parasites to human beings.[6]” Thus, because of man’s ability to adapt to any environment and use the resources available to him, population growth ensued. With this came the need for a change in subsistence strategy from hunting and gathering to farming and animal domestication in order to sustain a larger number of people within the society. This shift resulted in the production of surplus goods and the notion of wealth. With this, came the need for more organized governments and the protection of boundaries which led to McNeal’s notion of Macro-parasitism.

Mirroring the interaction between

parasites and humans, the development of governments eventually resulted in a

symbiotic relationship between rulers and subjects. As the peasantry provided goods and services,

the ruling class granted protection and religious affirmation. Initially, the relationship was quite

similar as to the first encounters between new microorganisms and humans. McNeal stated, “the hard-pressed peasantries

that supported priests and kings and their urban hangers-on received little to

nothing in return for food they gave up.[7]” Eventually, reciprocal relationships ensued

which resulted in more stable forms of societies. However, such stability had its drawbacks for

along with it came a sudden increase in population in a relatively small

area. Because these conditions were

greatly conducive to microbial infections, diseases and illnesses attacked

these large civilizations. Furthermore,

since there were large numbers of human hosts, micro-parasites thrived. One of the examples given by McNeal was the

outbreak of the plague in

After recovering from these various conditions and gaining immunity, the populations of European countries once again increased while relegating some of these once debilitating ailments to mere “childhood diseases.[14]” As a result of this new found “health,” the sharp rise in population led to another macro-parasitic act, the need for expansion and subjugation through armed conflict.

Unknowingly, European expansionists

brought, within their bodies, potentially lethal parasites the rest of the

world had yet to encounter. Because of

their developed immune systems, they were not affected by the micro-parasites

they carried. However, inhabitants of

isolated areas like the American continent proved to be highly susceptible to

these afflictions. McNeal stated, “No

wonder, then, that once contact was established, Amerindian populations of

In conclusion, William McNeal displayed a capacity for detail as he traced the relationship between microorganisms and the development of humanity throughout history. He also demonstrated his understanding of social evolution as he paralleled the human-parasite relations with large scale, communal interactions he termed as macro-parasitism. However, there were times he gave too much credit to the microscopic world in shaping the fate of man when history dictates that man was the master of his own destiny and the actions he took either led him to triumphs or failures. Granted the inability of man to defend himself against these invisible assailants limited his choices. Nonetheless, the destiny of humanity was still determined by those choices, limited they may be.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

McNeal, William. Plagues

and People. [