|

|

Alimentary

tract and pancreas Alimentarni

trakt i pankreas |

||

|

1 Institute for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, Clinical Center of Serbia, Medical Faculty University of Belgrade 2 Department for Infectious Diseases, General Hospital of U`ice 3 Medical Faculty University of Belgrade. |

ARCH

GASTROENTEROHEPATOL 2003; 22 (No 1 - 2): 12 – 17 Epidemiological

and clinical data

of outpatients with chronic

viral hepatitis Epidemiolo{ko-klini~ki

podaci ambulantnih bolesnika

sa hroni~nim virusnim hepatitisom (

accepted May 29th, 2003 ) |

||

|

Key

Words: chronic

hepatitis, Hepatitis

C Virus, Hepatitis

B Virus |

Abstract Total

of 212 outpatients with chronic hepatitis were evaluated. Patients were

followed-up at lest six months

to two years. Clinical, laboratory, ultrasonography examination and viral

serological tests were performed

for differential diagnosis. Viral infection was discovered in 179 patients (Hepatitis

C Virus, Hepatitis

B Virus, and co-infection with both viruses in 122, 56 and 1

patients, respectively). Distribution by

age confirmed more numerous young patients (from 21-30 years) in chronic

hepatitis C, while majority of

patients with chronic hepatitis B, were older (from 41-50 years). The higher

prevalence of male gender

was in both groups. Epidemiological data were positive in about half of

patients with chronic C hepatitis,

while majority of patients with chronic hepatitis B were without known route

of infection. Most

patients with chronic hepatitis C were recognized as intravenous drug abusers

(48%). Analyzed alanine

aminotransferase values confirmed mild elevation in the majority of patients

(45.28%), independent of

etiology. The most frequent associated disease in both groups was fatty liver

of unknown cause.

Clinically, investigated patients were mostly presented as mild chronic liver

disease, exceptionally, with

liver cirrhosis. In

conclusion, majorities of outpatients are young males with Hepatitis

C Virus infection, mostly drug abusers.

Histology assessment of liver tissue would yield more information on

differential diagnosis, eventually

associated disease, and stage of fibrosis that is crucial for disease

progression. Sa`etak Ispitano

je ukupno 212 ambulantnih bolesnika sa hroni~nim hepatitisom. Bolesnici su

pra}eni od {est meseci do dve

godine. Radi diferencijalne dijagnostike, ura|ena su klini~ka i

laboratorijska ispitivanja, pregled ultrazvukom

kao i virusolo{ki serolo{ki testovi. Virusna infekcija je na|ena u 179

bolesnika (hepatitis C virus: 122, hepatitis

B virus: 56, konfekcija sa oba virusa :1). U odnosu na uzrast, u

bolesnika sa hroni~nim C

hepatitisom najbrojnijie su bile mla|e osobae (od 21-30 godina), dok je

ve}ina bolesnika sa hroni~nim B

hepatitsom bila starija (od 41-50 godina). U obe grupe bolesnika dominirali

su mu{karci. Pozitivne epidemiolo{ ke

podatke je imalo oko polovine bolesnika sa hroni~nim C hepatitisom. Ve}ina

bolesnika sa hroni~nim

B hepatitisom nije imala podatke o na~inu zaraze. Intravenski narkomani su

bili najbrojniji me|u

bolesnicima sa hroni~nim C hepatitisom (48%). Vrednosti alanin

aminotransferaze su bile umereno povi{ene

u ve}ine bolesnika (45.8%), nezavisno od etiologije. Od udru`enih bolesti,

masna jetra neprepoznatog uzroka

je bila naj~e{}i nalaz u obe grupe bolesnika. Ve}ina bolesnika je imala bla`i

klini~ki oblik, ciroza

jetre je bila retka. U zaklju~ku, najbrojnije ambulante bolesnike ~ine osobe

sa hroni~nim C hepatitisom, uglavnom

mla|eg uzrasta i epidemiolo{kim podacima o intravenskom konzumiranju droge. Histolo{ka

procena tkiva jetre bila bi zna~ajna radi detaljnije diferencijalne

dijagnoze, otkrivanja eventualnih drugih

stanja i odre|ivanja stadijuma fibroze kao najzna~ajnijeg faktora za progresiju

bolesti. |

||

|

Klju~ne

re~i: hroni~ni

virusni hepatitis, Hepatitis

C Virus, Hepatitis

B Virus |

|||

|

|

INTRODUCTION Chronic

viral hepatitis (CVH) is a global public health problem.

Two primarily hepatotropic viruses, Hepatitis C virus

(HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV),

are main causes of the

disease. It is estimated that approximately 400 million, and

up to 200 million of individuals in the world, suffer from chronic

viral B and C infections, respectively (1,2). Viral transmission

is mainly parenteral, sexual and perinatal. Other

ways of transmission (percutaneous and nosocomial), occur

as well (3-7). Fortunately, rigorous screening practices diminished

the risk of transmission through blood transfusion. The

pathogenesis of CVH is still unclear. Replicating in hepatocytes,

viruses are capable to produce persistent infection and

as a consequence, chronic inflammation of the liver. Liver

damage mainly stems from cellular immune response, but

many other factors can influence its clinical presentation and

final outcome (8,9). Alcohol use, male sex, age at disease acquisition,

co-infection with HBV and HIV,

genetic background,

metabolic diseases (type II diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia,

iron overload), high body weight, even smoking,

etc., are associated with more rapid disease progression, particularly

in chronic hepatitis C (CH-C) (10-19). Clinical

course of CVH can be extremely various and is nonpredictable. It

may have a wide spectrum of features, ranging from

non-symptomatic to severe hepatitis ending to liver cirrhosis,

or even, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) (20-22). Efforts

to discover infection, understanding clinical manifestations and

natural history of the disease, careful monitoring of

patients, and eventually, offering antiviral therapy, are

critical to prevent progression of the disease and its serious sequelae. AIM

OF STUDY The

aim of this study was to investigate some of epidemiological and

clinical data of outpatients in order to characterize

them as a particular group of patients with chronic

viral hepatitis. Study objectives were following: -

Estimate the etiology of chronic viral hepatitis in outpatients -

Analyze demographic data of patients comparing with aetiology -

Identify the route of viral transmission and the risk of infection -

Notice other diseases as co-factors that could be important for

the disease progression -

Interpret the results of ALT values as a parameter for liver

necrosis -

Evaluate the stage of the disease on the basis of clinical picture

and radiological imaging PATIENTS

AND METHODS Total

of 212 outpatients with chronic liver disease (138 males,

74 females; age range: 13-76 years) was randomly included

in this investigation from January 2000 to December

2001. Patients were followed-up at Hepatology Clinic

at least six months to fulfill criteria of chronic hepatitis. Participants

were pending for liver biopsy, although some of

them refused it or had relative or absolute contraindications. They

were not hospitalized, nor received antiviral therapy before

the investigation. All analyzed parameters were taken

retrospectively, including demographic data, behavioral and

other risk of infection, alcohol or drug consumption, symptoms

of the disease, and clinical findings. As well, routine laboratory

analyzes (glucose, nitrogen, blood count, lipids,

etc.), liver function tests: alanine aminotransferase (ALT),

albumin, PT, PTT etc., and ultrasonography findings of

the upper abdomen, were performed. For differential diagnosis of

chronic or other liver diseases (hereditary metabolic diseases,

autoimmune hepatitis, liver cancer, etc.), selected tests

(ceruloplasmin, alpha 1 antitripsin, autoantibodies etc.), and

tumor markers (AFP and CEA), were done. Patients suspected for

liver or other malignancy were excluded from the study.

Serological tests for HBV, HCV,

and HIV markers were done

by third generation enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) with commercial kits. Positive anti HCV

sera was confirmed

using recombinant immunoblot assay (RIBA). Statistical

analysis was done for parametric and non-parametric data

(Student's t test, x2

test). A p<0.05 was considered significant. RESULTS 1.

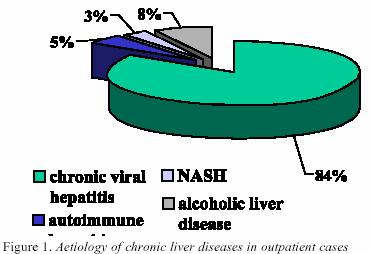

Aetiology of chronic liver disease The

etiology of chronic liver disease is shown in Figure 1. The

majority of 212 studied patients had chronic viral hepatitis

(84%) (DF=5; x2

=300.2;p<0.01). Autoimmune

hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease and nonalcoholic liver

steatosis/steatohepatitis (mainly caused by type

II diabetes mellitus and hypelipidemia), were other discovered diseases,

but in a significant lower number of patients.

Liver steatosis or steatohepatitis were defined by ultrasonography

finding of fatty liver depending on presence of

ALT elevation. 2.

Aetiology of chronic viral hepatitis Among

of 179 patients with chronic viral hepatitis, mostly (122/179;

68%) of them had HCV infection.

A significant lower

number (56/179; 31%) of patients had chronic B hepatitis

(DF=5; x2

=300.1;p<0.01). One patient

had dual infection with both viruses.

3.

Gender of patients with chronic viral hepatitis The

overall prevalence of male gender in total number of

patients with chronic viral hepatitis was significantly higher

in males: 64% than females: 36% DF=1;x2=0.11;p<0.05). Prevalence

of male gender was also significantly higher in

each group of patients with CH-C (DF=1; x2=8.5; p<0.01),

and CH-B (DF=1; x2=5.8;p<0.05). 4.

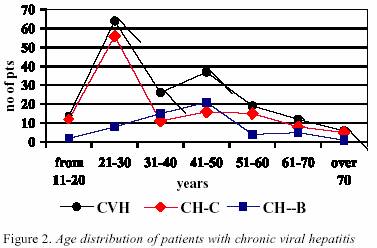

Age of patients with chronic viral hepatitis Age

distribution by etiology in patients with chronic viral

hepatitis is shown in Figure 2. Mean

age of patients with chronic viral hepatitis was 38 years

(8=38.6;SD=14.8). Group of patients aged from 21- 30

years was most frequent (DF=6; x2=87.8;p<0.01).

Age of

patients with CH-C were from 13-76 years (8C=35.8; SD=15.7),

while patients with CH-B were aged from 17-71 years

(8B=41.5;SD=12.9).

Analyzing

age by etiology of CVH, significant difference was

noticed between patients with CH-C and CH-B; patients

with CH-C were significantly younger than patients

with CH-B (DF=6; x2

=33.3;p<0.01). Group

of patients aged from 21-30 years was the most frequent

in CH-C, while in CH-B, the most frequent group included

patients from 41-50 years (DFC=6;

x2=94.5;p<0.01; DFB=6; x2=41;p<0.01). 5.

Epidemiological data of patients a.

The overall prevalence of positive (73/122) and negative (49/122)

epidemiological data was similar in CH-C patients

(DF=1; x2

=4;p>0.05). In contrast, the majority of patients

(13/56) with CH-B had no epidemiological data of infection

(DF=14; x2=14;p<

0.01). Patient

with dual HCV and HBV

infection had no data about

its risk.

b.

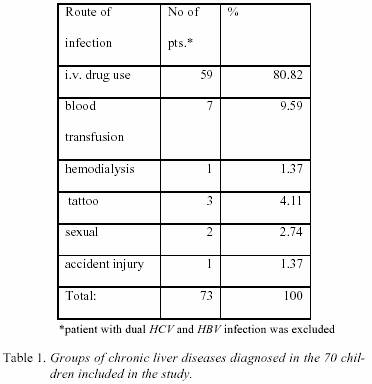

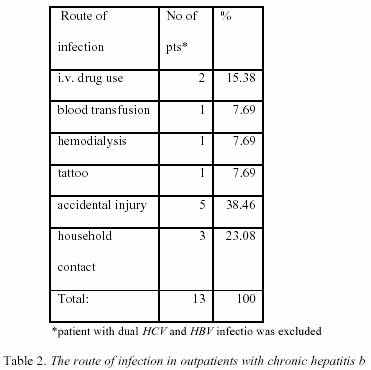

Patients with positive epidemiologal data were further analyzed

in details about the route of infection and the results

are shown in Table 1., and Table 2. The

majority of patients with CH-C had history data about

i.v. drug use (80%) (DF=5; x2

=198.8;p<0.01). In total

number of patients with CH-C, i.v. drug users were 48.36%. Seven

out of 73 patients received blood transfusion, other

routes of infection were less found. Among

patients with CH-B, 5/13 were infected by accidental injury.

All patients were healthcare workers, three of them

were dentists. Household contacts with infected person were

noticed in three patients.

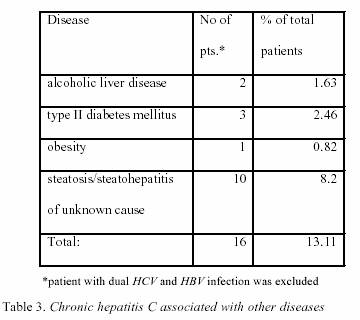

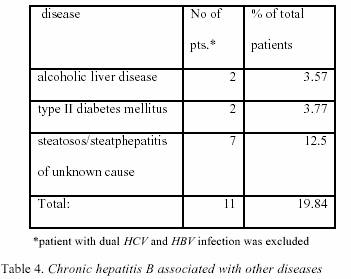

6.

Co-morbidity of chronic viral hepatitis with other diseases Investigations

of patients history, clinical and biochemical data,

and ultrasonography findings, revealed other diseases shown

in Table 3., and Table 4. The

most common finding of associated disease in patients

with CH-C was unknown caused liver steatosis/steatohepatitis

(10/16, or 8% of total patients with

CH-C) (DF=3; x2=2.77;p>0.05). Steatosis/steatohepatitis

of unknown cause was also the most

frequent finding in patients with CH-B (7/11 or 12% of

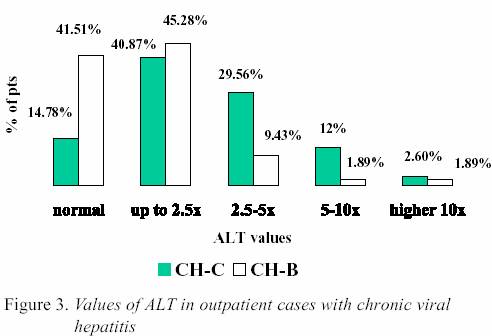

total patients with CH-B). 7.

Values of alanine aminotransferase in patients with chronic

viral hepatitis Values

of alanine aminotransfere were divided in 5 groups:

normal value, up to 2.5x, from 2.5-5x, from 5-10x, and

10x upper limit than normal value, respectively. The

results of ALT values are shown in Figure 3. 8.

Viral hepatitis Mild

elevation of ALT values (from normal-2.5x upper limit

of normal value), were noticed significantly most frequent in total

number of patients (45.28%) (DF=5;

x2=21.7;p<0.01). As

well, mild elevation of ALT values was most frequent in

the majority in each group of patients (CH-C: DF=4;

x2 =5.8; p<0.01) (CH-B: DF=4; x2=45.8;p<0.01). Comparing

etiology and ALT values, significant higher values

of ALT were noticed in patients with CH-C then in CH-B

patients (DF=5; x2

=16.7; p<0.01). Persistently

normal ALT values were defined by at least 3

determinations within screening period of 6 months or longer.

Normal values of ALT were found in 17/115 (14.78%%),

and 22/53 (41.51%) in CH-C and CH-B patients,

respectively. In CH-C patients, younger aged group

(from 20-31 years) was sifnificantly higher than

other

groups. (DF=5; x2=20.7;p<0.01).

In this group of patients,

CH-C patients, there was no difference between gender

(DF=9; x2

=0;p>0.05). In

CH-C patients with normal ALT values, positive antibodies

to HCV confirmed the diagnosis. HCV RNA was

not determined. In CH-B patients, HBeAg was done in 6/22

patients, and was negative. Analyzed

ALT values in CH-C patients with associated other

diseases did not show any significant difference (DF=3;

x2=2.77;p>0.05). 9.

Clinical features of patients with chronic viral hepatitis Evaluation

of clinical, biochemical and ultrasonography findings

of patients with chronic viral hepatitis confirmed that

mostly of them had chronic hepatitis without liver

cirrhosis (CH-C: 94%, CH-B: 93%). DISCUSSION Chronic

liver disease has different aspects. Patients usually

have no symptoms until liver cirrhosis and its complications developed.

Elevated aminotransferase values, often

at routine laboratory examination, usually take them to

hepatology units for evaluating possible liver disease. One

of the most important assignments for hepatologist is to

make correct differential diagnosis in order to recognize disease,

cure it with adequate therapy, and prevent its serious outcome.

Moreover, particular problem in outpatients were

wide spectrum of laboratory testings, careful clinical examination,

detailed history taking and epidemiological data,

and if necessary, additional radiological imaging that must

be done. Our

study was conducted in Hepatology Clinic which prime

purpose is in diagnosing and following-up patients with

infectious diseases. Exclusion or confirmation viral aetiology

in the spectrum of other chronic liver disease is the

first step for many general practitioners or gastroenterologists. From

diverse laboratories, blood transfusion units,

hemodialysis centers and phsyhiatric departments, patients

with positive hepatitis viruses are directed to visit our

Clinic for further clinical examination. Because of that, the

results of our investigation in two-year period strengthened the

fact that majority of outpatients (84%) have chronic

viral hepatitis, exclusively caused by HCV

and HBV.

Our study discovers more number of patients with chronic

HCV infection (84%) than CH-B, which is

also, general

epidemiological trend in other countries in the last decade

(1). Because of the similar transmission route, it was

expected a possible co-infection with both viruses and we

noticed it, but only in one patient. This

investigation confirms that males (64%) suffer from

CVH more than females, independently on aetiology. Past

data from the literature and our experience that persistence of HBV

is more often in males, are not completely resolved

until now. Some incomplete explanation was given

through interfering of hormones and viral replication. Recently

published epidemiological studies of HCV also

confirmed more inclination of males to become long term

carriers, after discovering that young females could eradicate

the virus up to 50% (23). At the same time, in our socioeconomic

milieu, males are more liable for behavioral risks

such as drug abuse and promiscuity what is critical for

percutaneous and sexual infection with both viruses. Intravenous

drug use has replaced blood transfusion as the

most common route of transmission of HCV. Approximately

90% of drug users after 5 years become infected

(24,25). Such drug use accounts for around two thirds

of HCV infections in U.S., and other developed countries.

As it was expected in our study, in CH-C, more frequent

patients were males, younger age (from 20-31 years)

and drug users (49%). On the contrary, majorities of patients

with CH-B had no data about infection and were older

than CH-C patients. Drug abuse as an epidemiological risk

is confirmed only in 15% of these patients. Interesting

data is that only one patient with CH-C (lower than

1% of total patients), was infected through hemodialysis. According

to data from several dialysis departments in

our country, almost 80% patients are infected with HCV (Dr.

S. Zerjav, personal communication). It

is worth to stress that among CH-B patients, 8/56 (14%)

were infected through accidental injury or household contacts.

This data requires use of preventive vaccination measures

of all healthcare workers and persons living with

infected patients, including sexual partners and other

relatives (26,27). The

specific factors that lead to progression of CVH are still

unclear. Investigation of associated diseases in our patients

discovered few patients with chronic consummation of

alcohol, type II diabetes mellitus and body overweight. But,

most frequent finding in our study was unknown

caused fatty liver estimated by ultrasonography. It

is almost equally presented in CH-C and CH-B (8% and 12%,

respectively), although that is more typical for CH-C (28,29).

It is notified that steatosis in CH-C can be conspicuous in

up to 60% by liver biopsy, induced by metabolic disturbances,

mainly diabetes mellitus type II and obesity.

Virus itself can be also a cause for fatty infiltration, particularly

in genotype 3, when its core and nonstructural part

of the genome (NS5A), disrupt intracellular uptake and

transport of lipids. However, only ultrasonography examination

is not complete for evaluation of fatty infiltration, especially

because of the fact that liver fibrosis can be expressed

as liver steatosis. Liver biopsy, what was not done

in our patients, certainly would be better to estimate and

differentiate this finding. Clinically,

CHV characterizes the insidious nature of the

disease and ALT values may be normal or fluctuate over

its course. Generally, mainly of patients have mild elevation

of ALT as it was noticed in our study (45%). In HCV

infection, extremely high values of ALT (more than 5-10

x upper limit of normal), can be found rarely, does not correlate

with disease progression or viral replication, even in

an acute hepatitis (20-22). During the course of CH-B, after

several years of infection, HBe antigen seroconversion is

followed with high elevation of ALT values in approximately

one third of patients. After that e.g. "elimination" phase,

the later course of the disease is relative benign

and is defined as "inactive". (30,31). "Inactive" disease could

explain lower activity of ALT values in CH-B, especially,

because of older age of patients. Another possibility could

be a high prevalence of drug users in CH-C in our

study, and combined toxic and viral effects on liver necrosis.

In addition, active drug use could explain that lower

prevalence of normal ALT values (14%), what was found

in other studies (approximately 30 %). Otherwise, normal

ALT values are found mostly in younger patients (aged

from 21-30 years), and without difference in gender. That

is in contrast to literature data that population with normal

ALT has distinct features, with inverted male to female

ratio and with no difference in age (32,33). As we had

not possibility to detect HCV RNA in outpatients, it is difficult

to differentiate if positive anti HCV antibodies in these

patients means present or, eventually past infection (34).

As well, in CH-B patients with normal ALT values, we

confirmed negativity of HBe antigen in 6/22 patients. Comparing

ALT values in CH-C patients associated with

other diseases that can accelerate progression of the disease,

we did not find a significant difference, and can not

conclude that this laboratory parameter, without histopatological

finding could be a "surrogate" markers for liver

necrosis and consecutive fibrosis (35-37). The

result that clinical feature of our patients was mainly without

cirrhosis (more than 90%), is explained by the fact

that patients with end stage of liver disease usually need

an intensive hospital care. Possible serious complications not

allowed these patients to be followed-up in the Clinic

for a long period. In

conclusion, the outpatients with chronic hepatitis in Hepatology

Clinic characterized viral infection, mainly with

HCV, and mild clinical features. High-risk populations are

young males, particularly drug users. Beside biochemical, clinical

and radiological imagining data, histopathological

examination is necessary for complete evaluation

of the disease. It can estimate possible associated disease

and stage of fibrosis that is most competent factor for

evaluation of disease progression. |

||

|

|

REFERENCES: 1.

National Institutes of

Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of Hepatitis C: 2002, June

10-12, 2002, Hepatology 2002; 36 (Suppl. 1):

S3-S19. 2.

Alter

M: Epidemiology of hepatitis B in Europe and worldwide. EASL Intern Consensus Conference on Hepatitis B. Program and Manuscripts, Geneva 13-14 Septembar,

2002: 73- 83. 3.

Brook

MG: Sexually acquired hepatitis. Sex Transm Infect 2002; 78: 235-40. 4.

Edlin

BR: Prevention and Treatment of Hepatitis C in Injection Drug Users. Hepatology

2002; 36: S210-219. 5.

Hagan

H, McGough JP, Thiede H et al: Syringe exchange and risk of infection with

hepatitis B and C viruses. Am J Epidemiol 1999;

149: 203- 13. 6.

Arai

Y, Noda K, Enomoto N et al: A

prospective study of hepatitis C virus infection

after needlestick accidents. Liver 1996; 16: 331-4. 7.

Zanetti

AR, Tanzi E, Newell ML: Mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis C virus. J

Hepatol 1999; 31(Suppl 1): 96-100. 8.

Cerny

A, Chisari FV: Pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis C: immunological features of

hepatic injury and viral persistence.

Hepatology 1999; 30: 595-601. 9.

Walsh

K, Alexander GJM: Update on chronic viral hepatitis. Postgrad Med J 2001;

77: 498-50. 10.

Poynard

T, Ratziu V, Charlotte F et al: Rates and risk factors of liver fibrosis

progression in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatology

2001; 34: 730-9. 11.

Wong

V, Caronia S, Wight D et al: Importance

of age in chronic hepatitis C virus

infection. J Viral Hepat 1997; 4: 255-64. 12.

Negro

F: Hepatitis C Virus and Liver Steatosis:

Is It the Virus? Yes It Is, but Not

Always. Hepatology 2002; 36: 1050-2. 13.

Wiley

TE, McCarthy M, Breidi L, Layden TJ: Impact of alcohol on the histological

and clinical progression of hepatitis C infection.

Hepatology 1998; 28: 805-9. 14.

-Caronia

S, Taylor K, Pagliaro L et al: Further evidence for an association between

non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus and chronic

hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 1999; 30:

1059-63. 15.

Renou

C, Halfon P, Pol S et al: Histological

features and HLA class II alleles in hepatitis C

virus chronically infected patients with

persistently normal alanine aminotransferase levels. Gut

2002; |

51: 585-90. 16.

Kuzushita

N, Hayashi N, Maribe T et al: Influence of HLA haplotypes on the clinical

course of individuals infected with hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 1998; 27: 240-4. 17.

Mori

M, Hari M, Wada I et al: Prospective study of hepatitis B and C viral infections,

cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and other

factors associated with hepatocellular

carcinoma risk in Japan. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 151: 131-9. 18.

Pessione

F, Ramond M-J, Njapoum C et al: Cigarette smoking and hepatic lesions

in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2001;34:121-5. 19.

Mohsen

AH, P J Easterbrook PJ, C Taylor C et al: Impact of human immunodeficiency virus

(HIV) infection on the progression of liver

fibrosis in hepatitis C virus infected patients.

Gut 2003; 52: 1035-40. 20.

Sherlock

S, Dooley J. Chronic hepatitis. In: Diseases of the Liver and Biliary

System. Sherlock D, Dolley J (eds). 10 th ed.

London, UK: Blackwell Science Ltd, 1997; 303-37. 21.

Dove

LM, Wright TL: Chronic viral hepatitis. In: Fridman LS, Keef EB. Handbook of liver

disease. Fridman LS, Keef EB (eds). Edimburgh

UK: Churchill Livingstone, 1998: 47-63. 22.

Niederau

C, Lange S, Heintges T et al: Prognosis of hepatitis C: results of a large

prospective cohort study. Hepatology 1998; 28: 1710-2. 23.

.Alter HJ: Hepatology

highlights, Hepatology 2002; 36: 778-80. 24.

Thorpe

LE, Ouellet LJ, Hershow R et al: Risk of hepatitis C virus infection among young

adult injection drug users who share

injection equipment. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 645-53. 25.

Hope

VD, Judd A, Hickman M et al: Prevalence of hepatitis C virus in current

injecting drug users in England and Wales: is harm reduction

working? Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 38-42. 26.

Roggendorf

M, Viazov S. Health care workers and hepatitis B: EASL Intern Consensus

Conference on Hepatitis B. Program and

Manuscripts, Geneva 13-14 Septembar 2002: 121-6. 27.

Van

Steenbergen JE, Working Group Vaccination High-risk Groups Hepatitis B for The Netherlands: Results of an

enhanced-outreach programme of hepatitis B vaccination in

the Netherlands (1998-2000) among men who

have sex with men, hard drug users, sex

workers and heterosexual persons with multiple

partners. J Hepatol 2002, 37: 507-13. 28.

Castéra

L, Hézode C, Roudot-Thoraval F et al: Worsening of steatosis is an

independent factor of |

fibrosis progression in untreated

patients with chronic hepatitis C and paired liver

biopsies, Gut 2003; 52: 288-92. 29.

Rubbia-Brandt

L, Qaudri R, Abid K et al: Hepatocyte steatosis is a cytopathic

effect of hepatitis C virus genotype 3. J

Hepatology 2000; 33: 106-15. 30.

Yuen

MF, Yuan HJ, Hui CK et al: A large

population study of spontaneous HBeAg

seroconversion and acute exacerbation of chronic

hepatitis B infection: implications for antiviral

therapy. Gut 2003; 53: 416-9. 31.

Fattovich

G: Natural history of Hepatitis B. EASL International Consensus Conference

on Hepatits B. Program and Manuscripts,

Geneva13- 14 Septembar 2002; 47-62. 32.

Puoti

M, Magnini A, Stati T et al: Clinical,

histologic, and virological features of hepatitis C

virus carriers with persistently normal or

abnormal aminotransferase levels. Hepatology

1995; 21: 285-90. 33.

Stanley

AJ, Haydon GH, Piris J et al: Assessment of liver histology in patients with hepatits

C and normal transaminase levels. Eur J

Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996; 8: 869-72. 34.

Pawlotsky

JM: Use and interpretation of virological tests for hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;

36: S65-S73. 35.

Poynard

T, Bedossa P, Opolon P: Natural history of liver fibrosis progression in

patients with chronic hepatitis C: the OBSVIRC,

METAVIR, CLINIVIR, and DOSVIRC groups. Lancet

1997; 349: 825-32. 36.

Afdhal

NH: Diagnosing Fibrosis in Hepatitis C: Is the Pendulum Swinging From Biopsy to

Blood Tests? Hepatology 2003; 37: 972-4. 37.

Fontana

RJ, Lok ASF: Noninvasive Monitoring of Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C.

Hepatology 2002; 36: S57-S64. |