ARCH GASTROENTEROHEPATOL 2001; 20 ( No 1- 2 ):

Acute ischaemic hepatitis caused by progressive dissecting aortic aneurysm. A case report.

Akutni ishemijski hepatitis prouzrokovan progresivnom disekantnom aneurizmom aorte. Prikaz slučaja.

( accepted November 14th 2000 )

Gradimir Golubović, Ratko Tomašević, Ana Begić-Janeva1

Department of Gastroenterology, Service of Internal Medicine, Clinical Hospital Center Zemun - Belgrade, 2Institute of Pathology, Medical Faculty, University of Belgrade.

Address correspondence to: Professor Dr Gradimir Golubović

Department of Gastroenterology

Clinical Hospital Center Zemun

9 Vukova St, YU-11080 Belgrade, Serbia, Yugoslavia.

Tel. + 381 11 106 106

Key words: Ischaemic hepatitis, aortic aneurysm, rupture.

SAZETAK

Ishemijski hepatitis nastaje kao posledica smanjenja dotoka krvi u jetru zbog akutno nastale hipotenzije čiji je osnovni uzrok srčana insuficijencija ili šok različite etiologije.

Prikazan je slučaj bolesnika starog 62 godine koji je primljen na kardiološko odeljenje zbog malaksalosti, bolova u grudnom košu, hipotenzije, I smanjene diureze. Postavljena je sumnja na akutni fulminantni hepatitis zbog visokih transaminaza i laktične dehidrogenaze, poremećaja činilaca hemostaze i nastanka DIK-a, porasta azotnih materija u krvi i znakova encefalopatije. U toku hospitalizacije dolazi do iznenadne smrti pacijenta. Autopsijski nalaz je pokazao postojanje rupturirane disekantne aneurizma ascendentne, torakalne i abdominalne aorte sa tamponadom srca kao neposrednim uzrokom smrti. Histološkim pregledom jetre je utvrdjena centrolobularna koagulaciona nekroza hepatocita bez znakova inflamacije, entitet poznat pod imenom ishemijski hepatitis.

Ključne reči: Ishemijski hepatitis, aneurizma aorte, ruptura.

The clinical features of ischaemic hepatitis simulates acute virus or toxic hepatitis. Serum transaminases value may rise up to 100 times of normal, reaching concentrations of 5000 to 10000 IU/l. A similar rise of lactic dehydrogenase ( LDH ) is striking as well ( 5 ). Alkaline phosphatase is normal. This condition is possibly reversible if liver hypoperefusion is restored within 72 hours ( 6 ). The longer the period, liver damage is more pronounced and lethal outcome is more frequent ( 7 ). Dissecting aortic aneurysm with ensuing shock, visceral hypotension, and celiac artery occlusion due to abdominal aorta dissection may be another cause of ischaemic hepatitis. To our best knowledge this is the first reported and documented case of ischaemic hepatitis caused by aortic dissection.

At admission he was found to be pale, cold, sweaty, hypotensive with BP 80/50 mmHg, with thready pulse, without swollen neck veins, and signs of lung congestion. Cardiac action was rhythmic, tones were clear; no heart murmur was recorded. ECG showed normal rhythm and signs of left ventricular ischemia on the lateral wall. Laboratory analyses were: blood sugar 9.1 mmol/l, normal serum electrolytes, CPK 175 IU ( normal values < 80 ), BUN 12.4 mmol/l, serum creatinine 99 µmol/l. The blood picture was normal. Infusion of crystalloids of 1000 ml, parenteral metoclopramide, and 30 000 IU of heparin were administered presuming that his problems were caused by unstable angina pectoris, lateral wall myocardial ischemia, and gastro-cardial syndrome due. After 2 hours, patient , s symptoms were transiently subsided with BP increase to 95/60 mmHg. Next two days, his symptoms persisted except chest pain. His was weak with systolic BP varying between 90 and 105 mmHg. Partial oxygen pressure was 68%. At that time echocardiography demonstrated dilatation and concentric hypertrophy of the left ventricle, with normal contractility and systolic function. The aorta was very dilated at the valvulary and supravalvulary levels but without definite signs of aortic dissection. Pulmonary artery was normal. Transoesophageal echosonography was not performed due to technical reasons. At fourth day laboratory analyses showed transient trombocytopenia of 24000 x 109/, prolonged PT and PTT time, fibrinogen 1.4 g/l, and positive fibrin degradation products possibly indicating DIC but without mucosal and skin haeemorrhages. Aminotransferases were increased over 50 times ( AST 1776 IU/L, ALT 1180 IU/L ), LDH 2620 IU/L, while CPK was normal. Total serum proteins were 69 g/l, serum albumin 34 g/L, total bilirubin 32.6 µmol/l, blood sugar 4.2 mmol/l. The fifth day, the patient became extremely weak but without chest pain. Mild to moderate encephalopathy and progressive weakness appeared. At that point fulminant acute viral hepatitis with DIC was suspected and he was transferred to the Institute for infective diseases. HAV, HBV, and HCV infections were excluded by appropriate tests. On the fifth day of his illness the patient suddenly died.

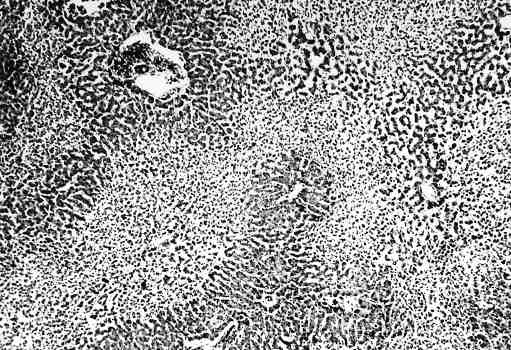

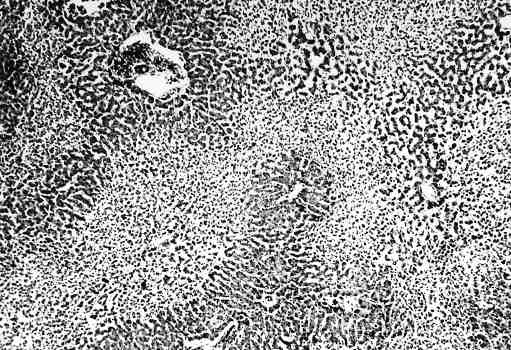

At autopsy dissecting aneurysm of the ascending, thoracic and abdominal aorta of the type 1 with cardiac tamponade were found. The main histological abnormality of the aortic wall was mild to moderate cystic degeneration of the media. There was blood collection within the aortic wall between the external and central part of the tunica media. The liver histology demonstrated changes of centro - central bridging coagulative ( ischaemic ) necrosis, sinusoid congestion and bleeding in the perivenular zone. FIGURE 1.

Increased oxygen extraction by the liver in situations of low hepatic blood perfusion ensures constant oxygen consumption within the limits of hepatic flow. A reduction in hepatic flow greater than 70% results in decreased oxygen uptake. In significant hypoperfusion states and shock hepatic arterial vasospasm and intense splanchnic vasoconstriction markedly augment hypoxic liver damage. Liver exposure to severe hypoxia leads to morphological changes after 24 hours because of liver capacity to absorb initially almost 95% of the received oxygen ( 6 ). Hepatic failure with asterixis and coma as complication of circulatory failure and ischaemia usually develops 2 – 3 days after circulatory or heart decompensation.

In chronic respiratory diseases, elevated aminotransferases and microscopic changes of hepatocelular hypoxic damage are detected when blood oxygen saturation is < 35% even if cardiac index is normal, indicating that liver damage may occurs primarily as result of hypoxia ( 13 ). This is further supported by liver hypoxic damage in Pickwick syndrome, where there is neither hypotension nor heart failure ( 14 ).

In the clinical setting left and right ventricular failure often coexist, resulting in hepatic congestion. Therefore Rockey and his collaborators proposed that in the right heart failure, passive congestion of the liver has a great significance in the development of ischemic hepatitis, which is almost the same as in the left heart failure ( 15 ). Thus Cellarier defines ischemic hepatitis as a cardiac liver ( 16 ). Shock and hypotension during variceal bleeding in liver cirrhosis rarely lead to ischemic hepatitis because of decreased hepatic metabolism and lowered liver sensitivity to hypoxia ( 17 ). Greater clinical application of splanchnic vasoconstrictor drugs vasopressin and somatostatin in variceal haemorrhage may potentially change this balance by further increasing splanchnic hypoperfusion and promoting hepatic ischaemia ( 18 ).

Ischaemic hepatitis as result of low cardiac output may not be clinically obvious. Diagnosis is often based on the abnormal biochemical tests and a high index of suspicion. If the liver has been previously damaged by chronic congestive heart failure, acute circulatory failure may lead to the picture of fulminant hepatic failure. Fulminant hepatic failure with encephalopathy and coma as a complication of circulatory shock is rare and develops 2 – 3 days after the circulatory failure. Hepatomegaly, jaundice, and coagulopathy are detected in 25% to 59% of cases. Prognosis is poor.

In the ischaemic hepatitis laboratory abnormalities are very important ( 4,9 ). After the initial insult, marked and rapid elevation of serum transaminases especially AST, occur within 24 to 48 hours. They return to normal values depending on duration of liver ischaemia. Serum concentrations decrease to normal in 3 to 11 days if perfusion and oxygenation are restored and urine output is normal. A similar rises and falls of serum LDH concentration occurs because of liver hypoperfusion and metabolic acidosis. This help in differentiating ischemic from viral hepatitis, where LDH is mildly increased only ( 7, 8 ). Alkaline phosphatase generally remains normal. Serum bilirubin may occasionally rise but is rarely greater than four times the upper limit of normal. In ischaemic hepatitis elevation of creatinine phosphokinase ( CPK ) indicates global hypoperfusion and confirms the diagnosis. This pattern of biochemical changes was registered in our patient with striking increase of serum aminotranspherases and LDH while alkaline phosphatase and serum bilirubin were normal.

Markedly elevated levels of aminotransferases are seen characteristically in patients with acute left heart failure, acute worsening of severe chronic congestive cardiac failure, hypotension or shock. AST tends to be higher than ALT, due to the AST-rich cardiac myocytes (19,20 ). An increase of AST appears earlier than the increase in ALT. If the elevation in AST is due to cardiac failure or circulatory shock, the level is falling within days of circulatory improvement. In contract, high AST level usually persists in cases of viral or drug- induced hepatitis and is independent of improvement of circulatory status. Beside ischeamic hepatitis very high levels of AST can be also found in patients with drug-induced or viral hepatitis, but ALT levels are usually higher in the later. In our patient AST concentration was 60 times higher than normal what with negative viral markers and the exclusion of toxic liver damage suggested ischemic hepatitis. The differential diagnosis between ischeamic hepatitis and acute hepatitis is not easy, especially if heart failure, hypotension and shock are present in the acute viral hepatic illness. Table 1.

Increased protrombin time is observed in over 80% of patients. This is not responsive to vitamin K. These patients are therefore very sensitive to warfarin. With successful treatment, protrombin time returns to normal within weeks. In our case prolonged protrombin time, decrease of platelet number, low fibrinogen and the appearance of fibrin degradation products possibly demonstrated DIC what it is bad prognostic sign. There is some evidence that after the operations of aortic aneurysm DIC complicating ischaemic hepatitis is the consequence of blocking of anticoagulative factors from aortic wall.

Definite diagnosis of ischaemic hepatitis is based on liver biopsy if general conditions and hemostasis status allow. Coagulative centrolobular ischemic necrosis of hepatocyts without significant inflammation reaction is characteristic morphological change ( 7 ).

Therapy of metylprednisolon , dopamine or ATP-Mg C12 is efficient in experimental animals, but not in clinical practice, where the best treatment should be directed to the cause of ischaemia ( 4 ).

The outcome of the disease is poor if the cause of hypotension and liver anoxia is not corrected ( 4,10,12 ). In ischaemic hepatitis prognosis depends on the cause of hypotension and patient , s cardiovascular status. The disease is oftenly mild and sometimes is not even diagnosed. Long-lasting liver hypoperfusion or circulatory failure superposed on already damaged liver and associated diseases of the other organs, may in turn cause fulminant hepatitis and have a bad prognosis ( 6,8 ). In our patient with clinical diagnosis of fulminant hepatitis, autopsy revealed dissecting aortic aneurysm and cardiac tamponade, which led to circulatory and forward cardiac failure, severe hypotension and histologically verified ischaemic hepatitis.

Cases of the patients with ischaemic hepatitis after the operation of aneurysm of abdominal aorta were already described (11). But we were not able to find published case of ischaemic hepatitis during the dissection of aortic aneurysm. In our patient hypotension was maintained for three days with value of systolic pressure between 80 and 105 mmHg. This is challenging classical teaching that prolonged hypotension with a systolic pressure below 80 mmHg for 10 hours or greater is required for significant liver ischaemia. In our patient dissection and haematoma of the aortic wall above the coeliac axis exit contributed to ischaemic hepatitis.

REFERENCES

THE CAUSES OF ISHEMIC HEPATITIS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

PICTURE 1.

Centro-central bridging necrosis of coagulative type, sinusoid congestion and bleeding in perivenular zone.