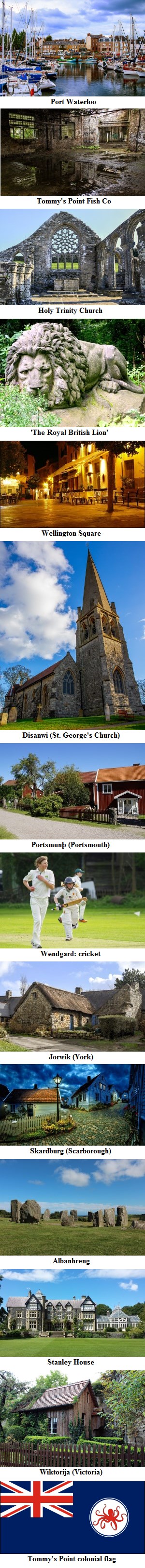

MekilhusanMekilhusan (English: Tommy's Point) is located on the Frilandic southwest coast and is part of the shire of Berglaft. The now insignificant village used to be a British crown colony from 1878 to 1928 and has therefore played a brief but important role in Frilandic history. The town has 9,320 inhabitants and consists almost entirely of Frilanders. 62% of the population is follower of Ferna Sed and 38% is not religious. In addition to standard Frilandic, many people speak the Mekilhusisk dialect, which is heavily influenced by English.  Important locations Important locations are marked on the map with a number, these are described below.  1. Port Waterloo

1. Port WaterlooPort Waterloo (Fri: Watarlauhaban) refers to the Battle of Waterloo and was constructed by the British as a support along the American trade route. It was also suitable for receiving large warships. After the British left, the port started to decline; nowadays it's only used by fishing boats and most port buildings have been demolished or changed function. 2. Abandoned cannery Derelict factory hall of the former Tommy's Point Fish Co. In the British era fish was canned here, nowadays the hall is mainly popular amongst homeless people and loitering youth. 3. Fort Edward ruin This small fort used to house the British garrison. It was located at the mouth of the Mužbak and served to defend the small island of Gibraltar (Kalpanberg). The rest of Mekilhusan also lay within reach of its cannons, so the Frilanders soon called it "ža žwangburg" (the coercion castle). After the British left, the fort was largely demolished, although some remnants of it are still visible. 4. Holy Trinity Church ruin Holy Trinity Church (Fri: Hailaga Žrehaidkirik) was an Anglican church that was looted and burnt to the ground after the British departure. The ruin is now listed as a monument. 5. Lion statue Statue "The Royal British Lion" (Fri: Ža Kununglika Britiska Lau) by artist Hiram Flaxman. The lion used to stand on Wellington Square as a symbol of British rule. Today it is located in a park on the Wenta industrial estate. 6. Haižhuf Cemetery Haižhuf (Heath Garden) is the oldest cemetery in Mekilhusan. It is the final resting place of, among others, author Ožalrika Harmansduhter (who promoted the Mekilhusisk dialect) and corporal Aunwulf Frisžessun (who died in the Fifth Frilandic-Hiverian War). 7. Wellington Square Wellington Square (Fri: Welungtunrum) is named after Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. It is the main square of Mekilhusan, where the market and many events are held. 8. Disir Temple The Disir Temple (Disanwi) used to be an Anglican church called St. George's Church (Fri: Wi-Jorgskirik). After the British left, the Ferna Sed community started using the building as a temple. Surrounding the former church is St. George's Cemetery (Fri: Wi-Jorgsgrabfelž), where Christians were buried. According to local legends, it's haunted by a Church grim (Fri: Kirikgrem); a guardian spirit who takes the form of a black dog and protects the cemetery from desecration. Originally, the creature also protected the church building, but it is believed to have been expelled from it when the church was turned into a temple. The gudar (Ferna Sed priest) of the Disir Temple makes an offering to the being every year, reaffirming the promise that the cemetery may remain Christian. 9. Town hall The town hall is located in the former governor's building. It is believed to be haunted; James Watson, the British governor's butler, once broke his neck after falling down the stairs. Since then his ghost has been playing pranks by knocking on doors and then whispering: "Ignore my tapping at thy chamber door; 'Tis the wind and nothing more." 10. The Anglo-Saxon Eatery The Anglo-Saxon Eatery (Fri: Ža Angulsahsiska Ethus) is a restaurant with typical British dishes such as pasties, meat pie, fish and chips, Yorkshire pudding, English breakfast and of course tea. 11. Wendgard sports fields The sports fields were named after the London district of Covent Garden, which in Frilandic bastardized to Wendgard ("Wind garden"). Football, rugby and cricket are played on these fields, which are a legacy from the British period. 12. King Wilhand Square King Wilhand Square (Fri: Kunung Wilhandrum) is named after king Wilhand, who ruled Friland from 1912 to 1946. It was built in 1930 together with the railway station. The square is mainly used as a parking lot. 13. Mekilhusan Station Mekilhusan station is a small terminus station that was built in 1930 to connect the village to the Frilandic railway network. 14. Chaucer Park Chaucer Park (Fri: Tjosergardil) is named after the British poet and writer Geoffrey Chaucer. It's a popular place for walking. 15. Freedom monument The Freedom Monument (Fri: Frihalsmendmark) was built in 1929 to commemorate the return of Mekilhusan to Friland. It depicts a Frilandic raven chasing away a British lion and was designed by Segrun Franksduhter. 16. Elven Ring Elven Ring (Fri: Albanhreng) is a so-called harrow (Fri: harug) or stone circle, where Ferna Sed followers leave offerings. It was built around 600 AD from local boulders and is the oldest building in Mekilhusan. 17. Stanley House Stanley House (Fri: Stainlauhus) is a typical British country house. It was built by Edward Stanley, Earl of Blenshire, in Frilandic better known as Audward Stainlau Hrudberhtssun, erl fan Blenga. After the British departure, the Stanley family was expropriated and the building redesignated as a sanatorium. Districts Below you can find a list of all districts of Mekilhusan. History Prehistory The Mužbak ("Mudbrook") is a narrow, shallow stream that must have been a source of fresh water even in ancient times. The oldest evidence of human habitation dates from around 300 AD and has been found in the Kalpanberg district. However, the finds are scarce and it seems that the area remained sparsely populated for centuries. The small lake southeast of Mekilhusan was created around 450 due to subsidence. In the British period the Mužbak was also called "Mudbrook" and the lake "Benjamin Lake", after British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. The Albanhreng ("Elven Ring"), a stone circle south of Mekilhusan, was built around 600 and indicates that the area must have been sufficiently organized at that time for such a large structure to be built. First mention The name Mekilhusan ("Greathouses") is first mentioned in a list of the possessions of count Wulfrik Bložžurstung Swerdhardssun, dating from 1390: 'Randaniž druhtin Wulfriks waldskap legjiž Mekilhusan. It es ni mekil and taljiž wainag husan, muglik standža žar sem ain hus žat storar wesža žan anžaran and es it žar afar namniž. Utar fiskarai habiž ža wilar lutil mainung.' ("On the edge of count Wulfrik's domain lies Greathouses. It isn't great and counts few houses, possibly it once had a house that was larger than others, which it was named after. Besides fishing, the hamlet has little significance.") The England crisis In the late 19th century, Mekilhusan was briefly world news due to the England crisis (Fri: Anglandfreg): the British Empire wanted to extend its influence to Friland, resulting in growing diplomatic tensions. Friland managed to avert an imminent invasion by giving the British full control over the insignificant hamlet of Mekilhusan for a period of fifty years. The British Empire knew that an invasion of Friland would cost more than it would yield and was content with this symbolic victory; its reputation on the international stage had been saved and, moreover, it now had its desired support on the Frilandic coast. On August 4, 1878, Mekilhusan became the British crown colony of Tommy's Point (Fri: Žomiskak), named after its first governor: Sir Thomas Oxney (Fri: hair Žomas Oksni Jakopssun). One of his letters to the home front shows that he was not very impressed with the place: 'The mere sight of this humble hamlet weighs heavily upon me: dilapidated dwellings, a hostile and ungodly population, its port unfitting for large ships and an unsatisfactory road network. Reshaping it into a pearl worthy of the British Crown shall be no small task; we have been truly swindled!' British rule The British invested heavily in their new crown colony: old Mekilhusan was largely demolished and rebuilt as the York district (Fri: Jorwik). The small island at the mouth of the Mudbrook (Fri: Mužbak) was developed into a fully-fledged seaport and named after Gibraltar (Fri: Kalpanberg). Fort Edward was built at the estuary to defend against land attacks, and coastal batteries were installed in the new port to withstand threats from the sea. Besides the British Union Jack, the new flag of crown colony Tommy's Point also featured an image of an octopus; the lucky symbol of Frilandic fishermen. Resistance Giving up Frilandic territory without a fight, no matter its size, was experienced as humiliating and shameful in Friland. In the Riksžing, politicians brawled over this issue and queen Algunž called Tommy's Point "a second Hiveria." It was soon decided to completely close the border at Tommy's Point, so that no more goods could go to or from the colony. The Frilandic population of Tommy's Point began to thwart British authority and attacks were carried out on British soldiers and Frilandic collaborators. The British responded with severe retaliation and deported anyone not loyal enough to their authority. Loyal British were appointed to all key positions and necessary goods were imported or manufactured locally. Growth and Anglicisation Tommy's Point grew quickly; partly through natural growth, but also through immigration of British nationals, who often worked as civil servants, soldiers or fishermen. Between 1878 and 1900 the districts of Scarborough (Fri: Skardburg), Victoria (Fri: Wiktorija) and Portsmouth (Fri: Portsmunž) were built. In 1910, the Winchester industrial estate (Fri: Wenta) was added. The English language was also gaining ground: it was taught in schools, it was the only language in which the news could be read, and it was spoken by the elite. Amongst the Frilandic part of the population, English gained a distinguished reputation and daily language became laced with English loanwords and pronunciations: the Mekilhusisk dialect, which is still spoken, is the result of this. Not speaking English, or at least Mekilhusisk, was considered backwards or even political. Return to Friland By agreement, Tommy's Point was to be handed over to Friland again on August 4, 1928, but approaching that date caused unrest: several generations had grown up on the edge of two cultures and after fifty years of being part of the British Empire, Tommy's Point had become more British than Frilandic. About 60% of the population was now British or of mixed British-Frilandic descent. The British Empire wanted to extend the period by another fifty years, which Friland refused. A new proposal, in which the economic system and many laws of Tommy's Point would continue to apply for another fifty years, was also rejected, as was the proposal to grant all British residents Frilandic citizenship. Friland only agreed to unconditional restitution, as agreed in 1878, and thus happened. Exodus and decline The return to Friland was accompanied by a massive exodus of British citizens. Many Frilanders who were pro-British or had converted to Anglicanism left with them. Radical Ferna Sed supporters, who viewed Christianity as the religion of the British and Hiverian occupiers, looted and set fire to Holy Trinity Church. An attack on St. George's Church was prevented by the new police force. Frustrated about the 50-year occupation of Mekilhusan, many Frilanders wanted to turn back the clock and erase every trace of British rule. Fort Edward and other symbols of British power were demolished, although the governor's building and Stanley House were spared. Due to the plummeted population, most of the houses were abandoned and entire districts became derelict. The port and many factories and warehouses were also abandoned, giving Mekilhusan the appearance of a ghost town. Reconstruction In the 1930s, the run down neighborhoods were largely demolished and rebuilt in a much more spacious manner: housing blocks gave way to detached country houses with large gardens, making Mekilhusan a popular place to settle for people looking for quietness and space. A proposal to replace the British district names was declined by the local council and Wellington Square and Chaucer Park could also keep their names. In 1930 King Wilhand Square and the railway station were built, connecting Mekilhusan to the Frilandic railway network. Revaluation From the 1950s onwards, there was a reappraisal of the traces left by British rule: this was no longer a disgrace to be erased, but an important part of the village's history, to be preserved for posterity. The handful of buildings that survived from that era were listed as monuments and an annual British festival was created, on which schoolchildren play typically British sports and people enjoy British cuisine together (and are sometimes horrified by it). The Mekilhusisk dialect, strongly influenced by English, is mainly spoken by the elderly, although there are certainly young people who can also speak it. In 1962, local writer Ožalrika Harmansduhter published the first book in Mekilhusisk: "Wes praud or žai Mekilhusisk lengwits!" ("Be proud of your Mekilhusish language!"), also translated into standard Frilandic as "Wes stult up žin Mekilhusiska sprek!" Today Mekilhusan is what it used to be for centuries: a small, quiet and completely unimportant village. But with a special British history, of which it even dares to be a little proud these days!  |