Lashawan Qadash

by Dr. Kawapar Ha-Tazawadaq

(

)

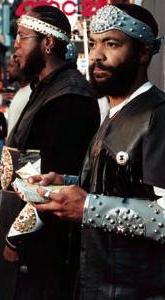

) Hebrew Israelites on 42nd street and 8th avenue, in Manhattan. |

Despite the spike in hostile emails, none of the correspondences produced a single refutation of the arguments presented in the original article. Moreover, most of the people who emailed us quickly lost interest and halted their responses. In the end, only two individuals continued to participate in online discussions. One was a person employing the pseudonym "Dragon," who asked that we visit his blog (which expresses sympathies for both the 12 Tribes group and the rival NOI), and only wanted to debate whether the FTMecca was run by the Jews. The other person was a man who adopted the Israelite name Yashiya Ahla (it was never established whether this might be High Priest Yashiya, of the ICUPK, nor did we bother to ask). It is the email correspondence with this second person that resulted in the writing of this article.

Yashiya's emails mainly covered two subjects: (1) the argument that 1 Samuel 16:12 uses that same word to describe David (admonee) that Genesis 25:25 employs when describing Esau, and (2) the issue of the spurious "Lashawan Qadash" dialect vis-a-vis the actual Hebrew language. With regard to the former argument, he was reduced to obstinately standing on a single claim (which seemed like a bluff) that when he checked the Hebrew text of 1 Samuel and Genesis, two completely different words were used (he has since retracted this assertion). With regard to the latter argument, Yashiya asked a number of questions about Hebrew that prompted us to attempt to write an article on the subject.

We should first (re)introduce the relevant subject. Certain Israelite groups (such as the Israelite Church of God and Jesus Christ [ICGJC], and the "House of Israel" group which Yashiya was associated with) claim to speak an ancient language known as "Lashawan Qadash," which is the true form of Hebrew. The main difference between Lashawan Qadash and modern Israeli Hebrew, is that the former does not possess the vowels o, e, or u, nor does it have consonants that produce the sounds f or v. The one vowel that Lashawan Qadash has that is not present in modern Israeli Hebrew is an 'I' (as in "pie" or "kite"), which is only produced by the ayin, the 16th letter of the Hebrew alphabet (proponents of the "Lashawan Qadash" dialect assert that this letter can only be pronounced as an 'I'). So in other words, they believe that the only sounds the Hebrew characters can make are the following:

However, it should be noted that Hebrew used to be written in the Phoenecian script, and the characters employed at the top of this page are from one version of that script which the Israelites prefer:

As a result, this is where the very name of their dialect comes from. In Hebrew,

(lashon qodesh) means "holy tongue". These Israelites opt to pronounce it "lashawan qadash". Similarly, they pronounce the popular greeting shalom as shalawam or shalam. With regard to this salutation, one Israelite group that broke away from the ICUPK, the 12 Tribes (HODC), has undergone some evolution. They originally claimed the greeting was shalam back in the mid-90s, before realizing that there was a vav in there. They switched to shalawam and later shalawm. Today they admit to not knowing Hebrew, and have apparently abandoned any claims about "Lashawan Qadash" (their web site now opens with the greeting "shalom").

(lashon qodesh) means "holy tongue". These Israelites opt to pronounce it "lashawan qadash". Similarly, they pronounce the popular greeting shalom as shalawam or shalam. With regard to this salutation, one Israelite group that broke away from the ICUPK, the 12 Tribes (HODC), has undergone some evolution. They originally claimed the greeting was shalam back in the mid-90s, before realizing that there was a vav in there. They switched to shalawam and later shalawm. Today they admit to not knowing Hebrew, and have apparently abandoned any claims about "Lashawan Qadash" (their web site now opens with the greeting "shalom").With that, we can now get to the issue of whether or not the claims about this dialect championed by these people reflect the realities of the Hebrew language. To date, no Israelite group has produced a single shred of evidence that their dialect is Hebrew in its pure form. Humorously, their claims about "Lashawan Qadash" are at times in conflict with other claims they make, though they are not aware of such contradictions due to the fact that they don't actually know Hebrew (not even in the fantastic dialect that they champion!).

For example, they parrot a claim, originally started by white supremacist 'Israelite' groups (such as the Christian Identity and British Israelism movements), that Britain was originally populated and ruled by "true" Israelites. Their proof? Well, they say that in Hebrew brit means "covenant" and ish means "man," therefore "british" means "covenant man" in Hebrew. Had they actually tried to square this up with their "Lashawan Qadash" dialect, they would realize that they should be pronouncing the word brit (

) as "barayath," and ish (

) as "barayath," and ish ( ) as "ahyash". In other words, they are unknowingly giving tacit approval of the very language they disdainfully call mere "Yiddish".

) as "ahyash". In other words, they are unknowingly giving tacit approval of the very language they disdainfully call mere "Yiddish".But this happens quite often. For example, when Robert "Alahyahawah" Denis (formerly Robert "Yawanathan" Denis), of Israelite.net first put out his editions of the Torah and TaNaKh in "ancient Hebrew," he merely (and quite hastily) changed the font of already existing texts so that Phoenician characters appeared. As a result, his "ancient Hebrew" Torah and TaNaKh still had the the niqqudot, which are a collection of dots and lines that help establish which vowels are present. While he has since quietly corrected this problem, it was a rather funny mistake, considering the fact that the creator of these books (unbeknownst to the serious libraries which now carry them) was himself a proponent of "Lashawan Qadash," which does not recognize the very vowels that the niqqudot represent. For another example, note that, at the time of this writing, the main banner on the front page of the current official site of the ICGJC still has the the niqqudot present in the Hebrew text of Genesis 1:1 which appears in the background.

While it is fun pointing out inconsistencies in the doctrine and actions of proponents of "Lashawan Qadash," we should attempt to approach a question alluded to by Yashiya via email: on what grounds should we believe that their claims about "Lashawan Qadash" do not reflect reality? What evidence do we have for or against a given pronunciation of the Hebrew characters?

One way to know how words were pronounced by ancient Jews is to see how they were transliterated into European languages. In this regard, few texts are more valuable than the Septuagint (LXX) [1, 2, 3, *], a pre-Common Era translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek. This source gives us tremendous insight into how the Jews pronounced certain Hebrew words more than 2,000 years ago. For example, in Genesis 25:26, the Septuagint renders Jacob as Iakwb (iakob). Note that it acknowledges the existence of an 'o' sound in the name (as is the case in modern Israeli Hebrew), and it also treats the ayin as making an 'a' sound (again, as is the case in modern Israeli Hebrew), rather than the mandatory hard 'I' that proponents of Lashawan Qadash claim must be voiced whenever the character is present.

In the same verse, the Septuagint renders Isaac as Isaak (isaak) and Rebecca as Rebekka (rebekka), which further hurts the proponents of "Lashawan Qadash," as the tsade in Isaac's name is not pronounced "taza", and Rebecca's name possesses the very 'e' sound that these Israelites claim does not exist in Hebrew. The Septuagint provides a plethora of other examples, such as the names Moab (Mwab), Ruth (Rouq) and Ephraim (Efraim), all of which testify to ancient Hebrew speakers employing pronunciations that those who champion the existence of "Lashawan Qadash" claim are not part of the language. So in the end we see that there is tremendous evidence for such pronunciations being part of Hebrew, which, in turn, serves as evidence against these Israelite groups.

With that established, we should consider a second question posed by Yashiya: "How can you decipher what sound a character makes just by looking at the character?" In modern Israeli Hebrew, novices of the language can employ the aforementioned niqqudot. But this system is a product of the common era, and it is not even employed in Hebrew books, newspapers or magazines. So how did ancient Israelites know how to pronounce a certain word? How do modern Israelis know how to pronounce the words they see in the newspaper in front of them? The answer is that this is due simply to knowing the rules of grammar and other aspects of the language.

This can best be explained by using an English analogy. How does one pronounce the word "wind"? The answer is that it depends on its place in a sentence. In the sentence "I will wind my watch" it is pronounced one way, while in the sentence "the wind is blowing hard" it is pronounced a different way. For another example, how do English speakers pronounce the letters 'ti' when they are together? Again, it depends, as in the word "time" they are pronounced one way, while in the word "position" they are pronounced differently. This has led linguists to joke that if we did not have these rules, one might try to spell "fish" G-H-O-T-I (with the 'gh' from "laugh", the 'o' from "women" and the 'ti' from "position").

When this was originally discussed with Yashiya, however, an Arabic analogy was employed instead of an English one. It was noted that like Hebrew, Arabic has an alphabet composed entirely of consonants. The language has also developed a system of lines that establish vowels for novice speakers (or for foreign or unknown words/names), the nuqat. Nonetheless, just as Israelis read Hebrew newspapers without the vowels present, Arabs read Arabic newspapers without the nuqat. They're able to know how to pronounce the words because they understand the grammatical structure of their respective language. This seemed like a clear enough explanation. Yashiya, however, responded as follows in an email from August 27th:

- Oh, now I see what your problem is. You think Arabic and Hebrew are the same. Well they're not.

"Since the beginning of the nineteenth century there has been a constant recourse to Arabic for the explanation of rare words and forms in Hebrew; for Arabic though more than a thousand years junior as a literary language, is the senior philosophically by countless centuries. Perplexing phenomenon in Hebrew can often be explained as solitary and archaic survivals of the form which are frequent and common in the cognate Arabic. Words and idioms whose precise sense had been lost in Jewish tradition, receive a ready and convincing explanation from the same source. Indeed no serious student of the Old Testament can afford to dispense with a first-hand knowledge in Arabic. The pages of any critical commentary on the Old Testament will illustrate the debt of the Biblical exegesis owes to Arabic."With that, we'd like to comment on some quick (and basic) similarities between the two languages. As was noted above, Arabic, like Hebrew, has its entire alphabet being made up of consonants. Though the Arabic script is morphologically different from the Hebrew script, the letters are mostly the same. Those who wish to see just how similar the two alphabets are might enjoy viewing an online comparison of the Arabic and Hebrew alphabets. The same site has a bit on the Israelite dialect under discussion here, and even shows which version of the old Phoenecian script that they prefer.

[Alfred Guillaume, The Legacy Of Islam, (Oxford, 1931), p. ix]

After the alphabets comes the triliteral nature of almost every root in either language. The triliteral roots of Hebrew and Arabic give the languages a three dimensional nature that is not found in European languages. One text on Semitic grammar compares this to what is found in the Indo-Europeans languages:

"With very few exceptions, the most important of which are the pronouns, every Semitic root, as historically known to us, is triliteral; it consists of three letters, neither more nor less, and these three are consonants. The vowels play only a secondary role. The consonants give the meaning of the word; the vowels express its modifications. [...] The use of prefixes, affixes, and even infixes, is common to both families of languages; but the Indo-Europeans have nothing like this triconsonantal rule with its varying vocalisation as a means of grammatical inflexion."The most basic root of either language is the feh-ayin-lamed (Arabic: faa-ayn-lam) root, which has the meaning "to do":

[William Wright, Lectures on the Comparative Grammar of the Semitic Languages, (Cambridge University Press, 1890), p. 31]

This spealling also represents the third person, masculine, past tense (or perfect tense) conjugation of the first verb stem of this root. By adding in the vowel sounds, we make an advance towards grammatical meaning. So, "he did" in Hebrew is hu pa'al, and in Arabic is hu fa'ala. Though they are pronounced slightly differently, they are spelled essentially the same way:

For the first person conjugation "I did," Hebrew gives us ani pa'alti and Arabic gives us anaa fa'altu, which again, are essentially the same:

To move to the first person plural "we did," Hebrew gives us anachnu pa'alnu and Arabic gives us naHnu fa'alnaa, which, yet again, are essentially the same in terms of spelling (with alternating vavs and alifs):

And there are many other examples as one moves through the different conjugations and verb stems. These basic structures provide us with the grammatical skeleton for various other roots. To see how this works, we would like to look at the active participle of the first verb stem in each language (mainly because it provides us with the sounds that proponents of Lashawan Qadash claim do not exist in Hebrew).

In both Hebrew and Arabic, the active participle has two uses. One is simply as just that, an active participle, signifying one who takes part in the action entailed by the verb root. The other is present tense conjugation of the verb. So, staying with the verb root "to do" (pa'al/fa'ala), the active participle of the first verb stem (Form I) is po'el in Hebrew and faa'il in Arabic:

This signifies "doing" or "one who does". To explain how this serves as a model, imagine you have any triliteral verb root XYZ. The first verb stem (Form I) active participle of that root in Hebrew is vocalized XoYez, and in Arabic it is vocalized XaaYiZ. So, for the KTB root (for to write), "writer" is koteb in Hebrew (modern Israeli Hebrew: kotev) and kaatib in Arabic:

| ROOT: |  |

| PARTICIPLE: |  |

From the QTL root (for to kill), "killer" is qotel in Hebrew and qaatil in Arabic:

| ROOT: |  |

| PARTICIPLE: |  |

Relevant to the nomme-de-web employed by the author of this article, the KFR root (for "to deny" or "to disbelieve") gives us the word for "non-believer," which is kofer in Hebrew and kaafir in Arabic:

| ROOT: |  |

| PARTICIPLE: |  |

This long winded explanation has helped to show the grammatical similarities between Arabic and Hebrew, as well as give an brief example of the rules of such grammar. This helps answer the question on Yashiya's mind (as well as possibly the minds of many others who do not know a Semitic language): if you have only consonants, and don't have the vowel signs to guide you, how do you know how to pronounce a given word? The answer is that one knows how to pronounce a word based on their knowledge of the language's grammar, as well as the word's place in the relevant sentence.

What we have seen in this article is that there is evidence against the "Lashawan Qadash" dialect posited by certain Israelite groups. Furthermore, we have seen that, contrary to what some Israelites may think, there is a system by which speakers of Semitic languages (such as Hebrew) can determine which agreed-upon vowels are voiced in a given text. Thus far we have seen no evidence that their claims about "Lashawan Qadash" reflect reality. Nonetheless, if any proponent of this dialect would like to write a response (which gives evidence corroborating their claims), we'd be more than willing to provide a link to it here. We doubt, however, that this will happen any time soon. In the 90s the aformentioned 12 Tribes site provided much of their doctrine on their website. This left them open to public debate, and their doctrines on Biblical exegesis and ancient Hebrew were often torn apart. Today, it seems, no Israelite group (along the lines of the ICUPK) presents its doctrines online for public scrutiny and debate.

KEY WORDS FOR SEARCH ENGINE: black israelites, black hebrew israelites, yahawah, yahawah-shi, yahawashi, yahawa-shy, i-bar-ya, la-sha-wan-qa-dash, real jews are black, adawam, ancient hebrew, esau, obadiah, edomites, www.icupk.com, ba ha sham, ba-hasham, israelite church of god and jesus christ, www.theholyconceptionunit.com, the holy conception unit