Mount Chambers Chasm

This page was created 2006/04/18, modified 2008/12/12

Written by Dave Clarke: email [email protected]

Photos by Ken and David Clarke

|

|

|

Eastern end of Mt Chambers.

The chasm, not visible in this small image, is just right of centre.

|

|

Mount Chambers and the beautiful Mount Chambers Gorge are about 60km

north-east of Blinman in the

Flinders Ranges

of South Australia.

This page is about a very unusual chasm on Mount Chambers.

The upper part of Mount Chambers is composed of a limestone that is resistant

to erosion. The resistance of the limestone and the greater erodability

of the underlying rock has resulted in the upper part of the mountain

being mostly surrounded by precipitous walls.

The climb to the top of the mesa is not as difficult as it might appear.

There is a gully a couple of hundred metres to the west of the chasm that

gives access for any reasonably fit person.

|

|

|

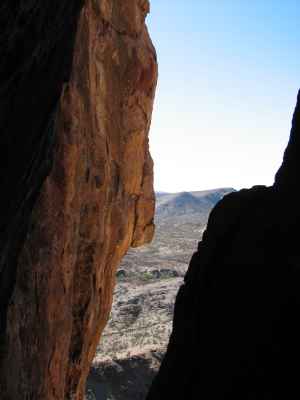

The view from near the chasm.

Chambers Creek winding through Chambers Gorge

|

|

|

Lake Frome in the distance.

A telephoto shot of the same view as shown on the right

|

|

|

Even if you are not interested in the chasm, the climb to the top of

the mesa is well worth the trouble, as the view pictured at the right shows.

The large salt lake, Lake Frome, can be seen to the east.

|

|

| |

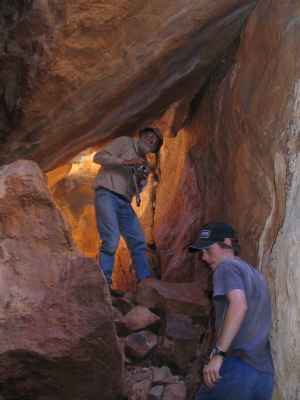

Cave

|

|

Rain water percolating through the limestone of the upper part of Mount

Chambers has formed caves, some of which are big enough to be worth exploring.

Unlike the chasm, if you want to explore the caves you must be prepared for

crawling on your belly through dirt and bat droppings. You should consider

taking torches, dust masks, hard hats and overalls.

|

|

|

The top of the chasm

Chambers Creek in the background

|

|

The chasm extends about 50 metres across the width of the Mt Chambers mesa

near its eastern end.

The coordinates at the south-eastern end of the chasm

are 30.95896 degrees south Latitude,

139.22879 degrees east Longitude; and at the north-western end,

30.95868 degrees south Latitude, 139.22836 degrees east Longitude.

The top of the chasm is about three metres wide at the south-eastern end

and two metres at the north-western end. In the photo at right,

my son, Ken, is standing about ten

metres from the south-eastern end of the chasm.

|

|

| The chasm, top and right.

We have not investigated the conspicuous opening in the left-centre of this

photo.

|

|

In the photo on the right

the top of the chasm can be seen extending from the cleft at the top

left to the upper right, near the reddish boulder.

The edge of the chasm is largely hidden in the shadow on the right of the

photo.

It seems that the eastern end of the mountain has somehow moved away from

the remainder. On our visit of 2006/04/16 we did not have as much time for

investigation as we would have liked, but it seems the top of the chasm is

wider than the bottom, so there is some hinging of the end of the mountain.

The bottom of the chasm is covered with rubble and soil that has fallen

from above. Some boulders have fallen only a part of the way down and have

bridged between the two walls.

I estimate that the depth of the chasm, from the top to the rubble on the

bottom, is around ten to fifteen metres.

I don't know how common or rare this sort of fracturing on mesas (or other

hills) might be; although I don't remember seeing it or reading about it

elsewhere. I suspect that the rock would have to be what geologists call

'competent'; ie. does not deform easily. Perhaps it requires a competent

caprock on a less competent base - the base sags and the cap fractures?

|

|

| | Looking into the chasm from above

|

|

The photo on the right gives some impression of the depth of the chasm.

It was taken from one of the

bridging boulders

, not from the top.

| | Looking toward the blockage at the south-eastern end

|

|

|

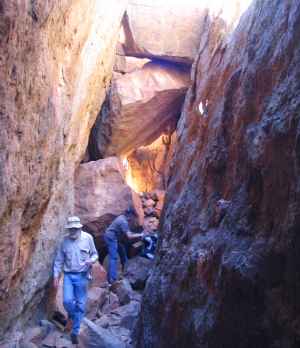

It is possible, with great care, but without any special climbing gear, to

climb down over some of the

bridging boulders

to the base of the chasm.

There is a section near the centre of the chasm where a V shaped set of

fractures comes off the chasm to the north-west.

The bridging boulders in this area seem

to provide the only path from top to bottom.

Visitors who intend to climb into the chasm should consider taking at least

about twenty metres of rope with them; it can be useful.

The photo on the left was taken from near the south-eastern end.

The blockage behind the second photographer is a barrier to going any further

along the bottom of the chasm in that direction.

| | An orb-spinner's web silhouetted against the sky

|

|

|

Looking up from part-way into the chasm; there are no clouds in the sky.

| | One of the bridging boulders

|

|

|

|

|

| | A rock pile that couldn't fall any further

|

|

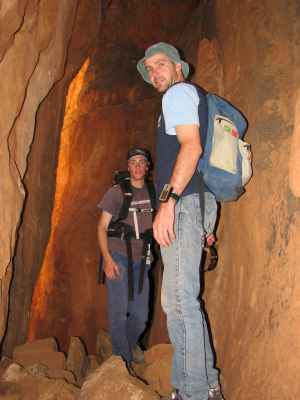

The next three photos show several of the places that boulders, having

fallen into the chasm, have bridged the space between the walls and not

been able to fall all the way to the bottom.

There were a number of places that following the base of the chasm is not

a simple walk. There are boulders to climb over and under, and a number

of fair-sized drops as you move toward the north-western end.

| | Coloured light

|

|

|

The golden-red glow from reflected sunlight and the blue light from the sky

made for very attractive colours on the rocks.

| | One of the darker places in the chasm - a flash was used

to take this photo

|

|

|

The photo on the left was taken at the bottom of the chasm. Although it

was a bright sunny day outside I found it necessary to use flash to get this

photo. The depth of the chasm and the bridging boulders above reduced the

light to the point where I was unable to hand-hold the camera (¼ second

at f2.7, 50 ISO). The glow in

the left background is from reflected sunshine on the walls further back.

|

|

| | Polished rock on projecting corner

|

|

At a couple of points we noticed that some projecting corners of rock

were polished quite smooth, apparently by rock wallabies that had got into

the chasm.

On an earlier visit my son and I had been surprised by one of

these remarkably agile animals. It would take a lot of rubbing for a

wallaby to polish this quite hard rock by rubbing on it; perhaps they have

lots of fleas?

| | Golden orb weaver spider web

|

|

|

It is possible to climb over and under the boulders in

the bottom of the chasm and work your way out to the north-western end.

At the point shown in

this photo we had to get beneath the web of a golden orb spider. (These

spiders are common in the Flinders Ranges, and seem to be harmless.)

|

|

| Looking out the north-western end.

Chambers Creek can be seen in the lower centre of the photo

|

|

The most difficult bit of climbing on the way out to the north-western end

is getting down over some wedged-in boulders near the end of the chasm.

The view on the right was taken from that point.

We found that a rope thrown over a large boulder that is securely lodged in

the chasm and tied around the chest was very useful in providing additional

safety in climbing down this section.

It seems that visitors are not likely to do much harm to Mount Chambers

Chasm and Mount Chambers. The only access is on foot, and the chasm and

all its contents are near indestructible. If I felt that increasing visitor

numbers would harm the area I would not have created this Internet page.

Of course one always hopes that visitors will behave responsibly, do as

little damage as possible, leave no rubbish, and not unduly frighten the

wild-life.

On the several occasions that I have visited the chasm I have found no

evidence of previous human activity. It would be great if this remains so.

More measurements need to be taken, especially of the depth and the width

both top and bottom. The width measurements should help decide whether the

chasm has opened by the bulk movement of one end of the mountain away from

the remainder, or whether there was more a hinging movement.

Is there a deep geological fault beneath the chasm, or is it only in the

surface several tens of metres? Is there lateral movement along the chasm,

or is the only movement the opening of the 'crack'?