The Native Indians of North America

The Blessings of the Great Mystery

‘We did not think of the great open plains, the beautiful rolling hills, and winding streams with tangled growth as "wild". Only to the white man was nature a "wilderness" and only to him was the land "infested" with "wild" animals and "savage" people. To us it was tame. Earth was bountiful and we were surrounded with the blessings of the Great Mystery. Not until the hairy man from the east came and with brutal frenzy heaped injustices upon us and the families we loved, was it "wild" for us. When the very animals of the forest began fleeing from his approach, then it was that for us the "Wild West" began.’

Luther Standing Bear, Sioux

Respect for the Land

"This land, these forests, are not just a resource to be harvested and managed. They were given to us to take care of and treat with respect, the way our grandfathers have always done. We are responsible for taking care of Mother Earth because Mother Earth takes care of us… We have lived with this land for many generations. We know its cycles. We know it won’t be the same after they take away the trees. The money is all that will be left.’

Bigstone Cree First Nation, Canada

North America

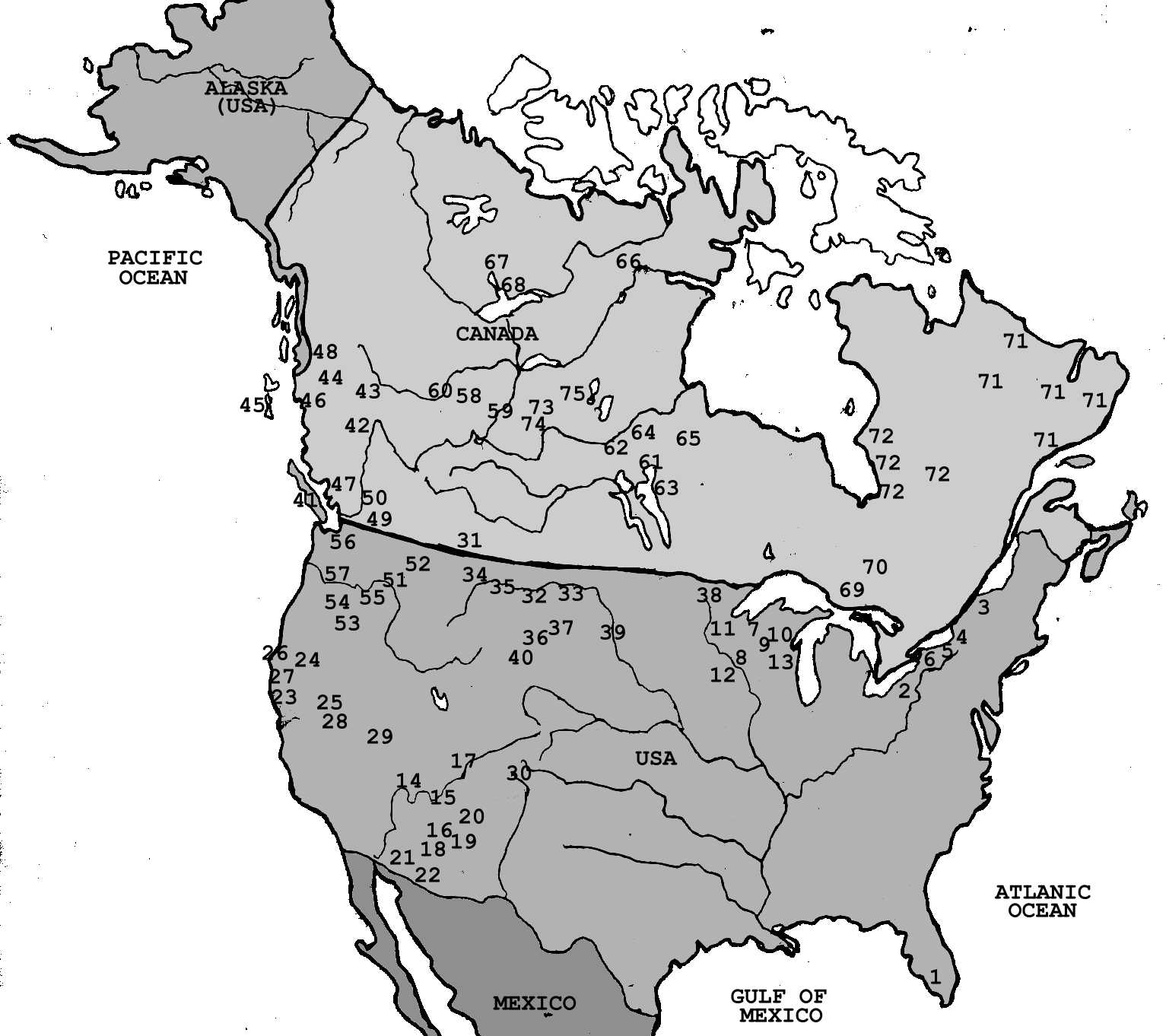

There are around three million Native North Americans living in Canada and the United States today. They belong to hundreds of different tribes and nations, ranging from the Navajo, with a population of about 230,000 and a homeland as large as the country of Belgium, to very small communities with only a handful of members and a few acres of land.

Native American cultures and ways of life vary greatly. Some groups continue to speak their own languages and to follow a traditional lifestyle, while others now live much like their non-native neighbours. More than half of all Native Americans live and work in cities, away from their own communities, although often they intend to return home when they retire.

Native Americans are thought to be descended from Ice Age hunters who crossed from Asia to Alaska more than 20,000 years ago. By the time Columbus ‘discovered’ America in 1492, Native Americans had evolved into many distinct peoples, ranging from small nomadic hunting groups in the far north to large farming nations in what is now the southern United States. Each group was closely adapted to its own area, and felt a deep attachment to the land and to the plants and animals with which they shared it.

The arrival of Europeans was a disaster for Native Americans. Millions were killed or displaced by settlers, who saw them as savages with no right to the land. Millions more died from European diseases against which they had no resistance. By the end of the nineteenth century, the native peoples had lost almost all their land, and their population had fallen from an estimated six million or more to only 350,000.

Today, Native North Americans are no longer being deliberately killed by the Canadian and US governments. Nonetheless, they still have a great many problems to contend with. Much of the remaining Native American land in the United States and southern Canada is affected by water shortage, pollution, mining, military activity or the growth of nearby non-native communities. Some tribes face threats to traditional activities such as hunting, fishing and food gathering. Many groups are trying to regain land that was taken from them illegally, or to prevent the destruction of important sacred sites, which are essential to their religion.

Further north, in northern Canada and Alaska, peoples such as the Innu and the Cree are facing an invasion of their homeland. Until recently, this vast area of lakes, forests and tundra had attracted few settlers, and the indigenous people could hunt, fish and trap like their ancestors. Although may groups have never signed treaties giving up their land, they are now threatened by many kinds of development: military training, diamond and uranium mining, oil and gas extraction, and hydroelectric projects, such as the enormous James Bay scheme in Quebec. Perhaps most devastating of all, multinational companies are clear-cutting the forests of northern Canada at the rate of one hectare every 30 seconds, causing immense environmental damage and destroying the indigenous people’s way of life.

Some Native North American groups have successfully adapted aspects of their own culture to help them survive. In the Southwest, for instance, many tribes sell pottery and other traditional handicrafts to tourists. A few have developed new activities, such as tourism and mining. Most, however, are plagued by poverty, unemployment and disease. They are also threatened by intense pressure, particularly from television and the educational system, to assimilate into mainstream North American society. This leaves many indigenous people demoralized and confused, and contributes to the high rates of alcoholism, suicide and social problems in their communities.

|

1 Traditional Seminoles 2 Cayuga 3 Mohawk 4 Oneida 5 Onondaga 6 Seneca 7 Bad River Chippewa 8 Lac Courte Oreilles Chippewas 9 Lac du Flambeau Chippewas 10 Mole Lake Chippewas 11 Red Cliff Chippewas 12 St Croix Chippewas 13 Sokoagon Chippewas 14 Havasupai 15 Hopi 16 Mojave & Yavapai 17 Navajo 18 Pima 19 San Carlos Apache 20 White Mountain Apache 21 Seris 22 Tohono O’odham 23 Hupa 24 Karok 25 Pit River (Achomawi) |

26 Tolowa 27 Yurok 28 Pyramid Lake Paiutes 29 Western Shoshone 30 Eastern Pueblos 31 Piegans (Blackfoot) 32 Assiniboine & Gros Ventres 33 Assiniboine & Sioux 34 Blackfoot 35 Cree & Chippewass 36 Crow 37 Northern Cheyenne 38 White Earth Chippewas 39 Lakota-Sioux 40 Arapaho & Shoshone 41 Nootka 42 Carrier 43 Carrier 44 Gitksan & Wet’suwet’en 45 Haida 46 Haisla 47 Lillooet 48 Nisga’a 49 Osoyoos 50 Okanagan |

51 Nez Percés 52 Kootenai-Salish 53 Klamath 54 Warm Springs 55 Umatilla 56 Snohomish 57 Yakima 58 Bigstone Cree 59 Cold Lake Cree & Chipewyan 60 Lubicon Lake Cree 61 Cross Lake Cree 62 Nelson House Cree 63 Norway House Cree 64 Split Lake Cree 65 York Factory Cree 66 Baker Lake Inuit 67 Dogrib 68 Yellowknife 69 Sheguiandah Ojibway 70 Barriére Lake Algonkins 71 Innu 72 James Bay Cree 73 Canoe Lake Cree & Métis 74 Flying Dust Cree 75 Lac La Hache Chipewyan |

INNU

The 13,000 Innu (not to be confused with their neighbours the Inuit, or Eskimo) are the indigenous people of a large area in north-eastern Canada. Their homeland, which they call Nitassinan, is a vast expanse of forests, lakes and rocky, windswept ‘barrens’. For most of the year it lies under a deep blanket of snow and ice.

The Innu survived here for thousands of years by hunting caribou and other animals. From September to June, small bands of perhaps two or three families would travel in search of game, walking on snowshoes and pushing their possessions on a sled. Then during the summer, the Innu would come together in larger groups at the coast to fish, make boats and meet friends and relatives.

Since the 1950s, their way of life has been coming under increasing pressure. The authorities have discouraged the Innu from hunting and tried to make them settle in permanent villages and send their children to school to become ‘Canadians’. Many Innu have become confused and demoralized, and their communities are plagued by alcoholism, family breakdown and suicide. In one village, in 1993, a third of the adults tried to kill themselves.

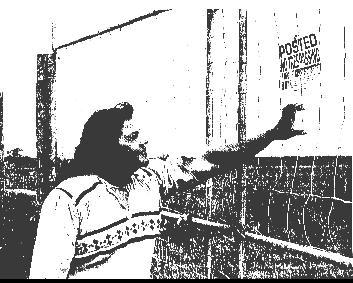

At the same time the Innu’s land, which they have never sold or surrendered to Canada, is seriously threatened by modern development. Hydroelectric and forestry projects are destroying or damaging thousands of square kilometres. The Canadian government is also using Nitassinan as a training ground for military pilots. Low-level jets fly at supersonic speeds close to the ground, terrifying the Innu and disrupting wildlife.

Perhaps most seriously, the discovery of mineral deposits at Voysey’s Bay on the Labrador coast threatens to bring thousands of miners flooding into the area. If that happens, according to one Innu leader, ‘It will mean the death of my people.’

ANIMAL MASTERS

The Innu believe that the animals they hunt are controlled by spiritual ‘masters’, who help the Innu to find and kill game. In return, they must show respect to the masters by following certain rituals and sharing the meat among themselves.

The most important ritual is Mukushan. A sacred food is prepared from the bone marrow of the caribou, and then everyone in the camp is invited to eat it at a special meal. It is essential that every scrap should be eaten, otherwise the ‘master’ may be angry and prevent them from killing more caribou.

TRADITIONAL SEMINOLES

The 200 or so Traditional Seminoles live in the dense, subtropical Florida Everglades, one of the last wildernesses in eastern North America. They are almost unique, still building their own straw-thatched houses, or chickees, and following a way of life based on hunting and fishing.

Although the US signed an agreement recognizing the Traditional Seminoles’ land rights in 1842, almost all their territory has since been seized by settlers or destroyed by development. The Traditional Seminoles are now reduced to being little more than squatters in their own homeland.

Recently, the US government has offered them millions of dollars in compensation for the loss of their lands. Although they are desperately poor, the Traditional Seminoles – unlike most other tribes – have refused. They explain: "The Great Spirit put the land here… We don’t believe in accepting money for the land because the land is not ours to sell.’ If the government does not respect their rights to live and use the land traditionally, they fear that they – and the Everglades they have protected for so long – may not survive.

For the Traditional Seminoles and the other indigenous peoples of the southeast, the Green Corn Dance is the most important festival of the year. Under the guidance of a shaman (or medicine man), they gather for five days to celebrate and renew their life as a people through ceremonies, rituals and meetings

Dannie Billie, a Traditional Seminole leader, says: ‘The Green Corn Dance difines who we are and what we are… It is the heart and soul of our way of life.’

The Traditional Seminoles are now trying to find a permanent site for the Dance so that their culture can continue.

SIOUX

The Sioux are one of the largest and best-known of all Native American groups. More than any other people, the represent what is often seen as the ‘typical Indian’: the mounted warrior wearing a feather war bonnet, living in a tepee and hunting bison on the windswept grasslands of the Great Plains.

During the nineteenth century, the Sioux and their neighbouring groups fought heroically against overwhelming odds to protect this way of life. Eventually, though, the United States defeated them by deliberately hunting the bison on which the Sioux depended to the edge of extinction.

Today, most Sioux live on reservations, but conditions are so bad there that many of them – like other Native Americans – are moving to the cities. The reservations are among the poorest communities in North America, with very high rates of unemployment, disease, drunkenness, suicide and accidental death.

The Sioux are trying to rebuild their pride and identity as a people. In particular, they want the United States to return Paha Sapa, the Black Hills, which were taken from them illegally in the 1870’s. They have refused compensation of more than $100 million because they believe these hills are the sacred centre of the universe, ‘The Heart of Everything that Is.’

Mining, tourism and other developments have already damaged Paha Sapa. Now the film star Kevin Costner wants to build a giant gambling and leisure complex there.

‘We have a prophecy.’ Says a modern Sioux, Charlotte Black Elk, ‘that 112 years after humans drive the last bear from the Black Hills, there will come a day of great, catastrophic change. So far as we know, there hasn’t been a bear there since the end of the 1880s. That doesn’t give us long to get the Hills back and return the bear to them.’

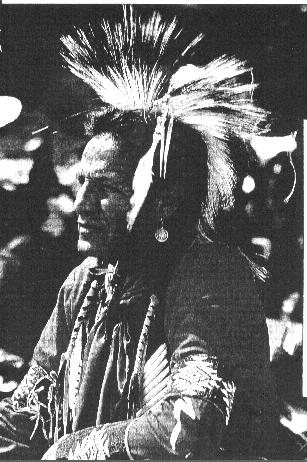

POWWOWS

Every summer, there are hundreds of powwows in Native American communities. For three days, dancers in brilliantly coloured headdresses and costumes perform, accompanied by singing and drumming. People have a chance to meet friends and relatives from different reservations and to enjoy traditional foods and customs.

TOTEM POLES

North-west coast peoples have always been superb artists. They wove beautiful clothes and blankets from shredded cedar bark, and carved intricate, brilliantly coloured masks used by dancers in the many festivals and ceremonies during the year. Most famously, they produced enormous, brightly painted totem poles.

A totem pole was really a kind of family tree that stood in front of the owner’s house. Often it shows not only human ancestors but also powerful animals like the raven and the wolf and mythical beings, such as the thunderbird, from which important families believed they were descended. A few outstanding native artists are still carving in the traditional way today.

GHOST DANCE

The North American Indians’ Ghost Dance cults stressed the need to return to Indian ways of life which were breaking down. The Indians believed that if the traditional patterns of life were restored, the buffaloes (being slaughtered by white settlers) would return and the dead ancestors would come back to defend them. The Ghost Dances were believed to be a way of driving the whites out of Indian territories by giving the Indians magical protection against the settlers’ bullets.

Led by prophets, these involved dancing rituals and the promotion of visions aimed at the removal of the white man and the return of land and resources to Indians, aided by their ancestors.