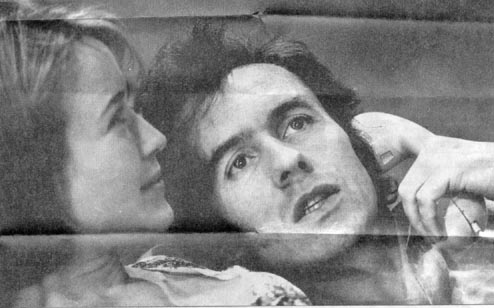

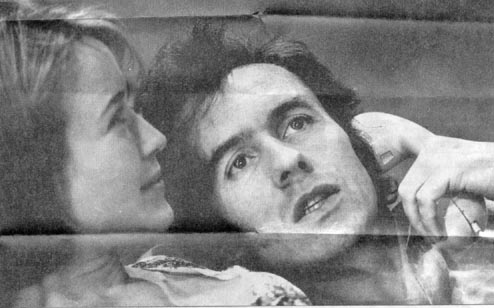

Jennifer Ehle and Stephen Dillane in The Real Thing: 'A Romance with a strong pulse.'

photo by Neil Libbert

At the Donmar, David Leveaux has directed an exquisite production of Tom Stoppard's The Real Thing. In 1982 Stoppard startled devotees of his intellectual arabesques with this play, which showed he had a heart, the 'real thing' in question being love. But the play now seems, though softer, not essentially more compassionate than Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, which so kindly rehabilitated marginal characters. It is a glittering vehicle, a multi-faceted illustration of its title, a display of the many things the reality of which can be imperilled by pale imitations. The Real Thing opens with a not-real thing - a joke-laden, artificial exchange between a couple, in the course of which it emerges that the wife has been having an affair. Just as the audience begins to feel definitively superior to yet another smart riposte, the scene ends - and proves to be a scene from a play, the subject of discussion between the playwright and his actress wife.

Just as the audience settles into thinking that this is going to be a piece about the distance between life on and off the stage, it turns out that there is indeed a love affair going on which involves the playwright. The not-real is quite real. This love affair - threatened but saved - is the beating heart of the play, and it is delicately rendered here. Jennifer Ehle, as the romantic interest who becomes a driving force, conveys exactly the right mix of bemusement and perception: her smiles are dewy, her voice is resolute; she is both melting and gritty. As the playwright, Stephen Dillane's restraint and ease are compelling: he moves from detachment to painful engagement without ever straining, simply increasing the crumples in his face.

This is a romance with a strong pulse, expressed in memorable moments: Ehle, climbing a twilit stairway to 'Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?' is an evocative sight. On the other hand, if you hadn't just heard a Stoppard speech, you might think you were watching a shampoo ad. This, of course, may be part of Stoppard's point, another elaboration on the real-versus-pastiche debate: are we watching romance or enduring devotion? And that's the trouble: almost anything can be part of his point: the dramatist's much-lauded philosophical tendency sometimes looks more like a tendency to accumulate a number of concerns and manufacture a label for them: 'real', in this play, is too elastic a term. Since Stoppard's work is full of pre-emptive strikes against a notional antagonist, he has already dealt in his play with some of my objections. There are two discussions in The Real Thing of what 'real' art is. There's a clever dissection of a substance-versus-style debate. There's also a funny look at posh versus popular music, though, partly due to the passing of 17 years, this is a bit wonky: the Righteous Brothers and Brenda Lee are no longer synonymous with the naffest taste - and even Neil Sedaka has had his revival. But no one would turn to Stoppard for a response to popular culture. Gilded with ironies, and with a tender core, The Real Thing could sail profitably into the West End. It would raise the tone there, but it won't change anything.

Back to The Real Thing Article Index