Branchiorectumidae

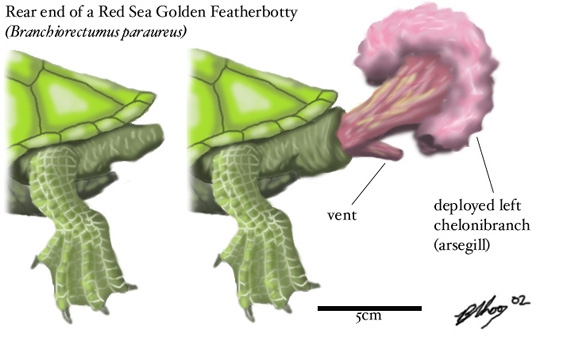

Featherbotties are a remarkable group of highly specialised marine pleurodires found in tropical and subtropical reef environments throughout the Indo-Pacific region. These colourful turtles possess paired feathery extensions of the distal gut (whose proper nomen is the chelonibranch but which is almost universally referred to as the "arsegill") that contain closely packed blood vessels. The arsegill can be deployed as a functional gill or retracted into a rectal pouch to avoid damage when on land or under attack.

(Picture by Brian Choo)Fig. 1: The arsegill array of the Red Sea Golden Featherbotty

(Picture by Brian Choo)Fig. 1: The arsegill array of the Red Sea Golden FeatherbottyThe forelimbs have become modified into flippers with 3-4 large claws. The hindlimbs are webbed but still retain functional digits. The tail has atrophied to the point where it is no longer externally visible. Featherbotties range in size from a carapace length of 15 to 55 cm.

The featherbotties dwell in high-energy marine areas where the water has a high dissolved oxygen content (eg. surge channels and seaward reefs). They anchor themselves to a hard surface with their powerful foreclaws and raise their posterior into the current using their hindlimbs as props if necessary. The deployed arsegill supplies sufficient oxygen and expels sufficient CO2 to allow the turtle to remain underwater for days without surfacing. The featherbotties use their powerful beaks to feed on a variety of organisms. Different species prey on small fish, molluscs, crustaceans, echinoderms, coral polyps and algae.

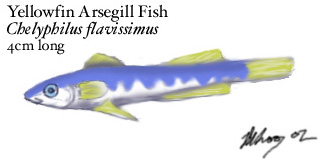

A number of fish and crustacean species are known to take refuge in featherbotty arsegills, aggressively defending their hosts against gill-nipping predators. In return, these symbiotic protectors feast on the scraps of the turtle's messy feeding or on plankton and organic debris trapped in the arsegill filaments.

(Picture by Brian Choo)Fig. 2 (gillfish jpg): The Yellowfin Arsegill Fish. One of many colourful species that associate with Featherbotties.

(Picture by Brian Choo)Fig. 2 (gillfish jpg): The Yellowfin Arsegill Fish. One of many colourful species that associate with Featherbotties.Some species of coral-eating featherbotty (the "bumstingers") store nematocysts extracted from their prey in their brightly coloured arsegill filaments forming a potent anti-predator defence.

Female featherbotties come ashore to lay their eggs, burying their eggs in beach sand, often coming together in spectacular arribadas. The hatchlings are exact miniatures of the adults and immediately attempt to eke out an existence of the reef. Unlike other marine turtles, featherbotties do not normally migrate far from their nesting sites. This has led to a high degree of speciation due to the increased likelyhood of isolated populations forming on different tropical islands.

23 species of featherbotty have been described with at least as many on the way. The exact number of species has been obscured by the presence of several widely distributed species-complexes comprised of very similar forms in the South Pacific.