|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Mexican Imperial Army |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

During the early years of the so-called Mexican Adventure the war against the republican rebels under Benito Juarez was, of course, carried out by the French Imperial Army of Napoleon III. The Miramar Convention signed by the French and Maximilian stipulated that French troops would remain in Mexico for three years and that the famous French Foreign Legion would stay for six years. It was also called upon to subsidize the Mexican Imperial Army which was officially formed in the fall of 1863 at the request of Emperor Napoleon III. For both political and practical reasons he was anxious that a large local military force would be established in Mexico to show that the new Mexican Empire was truly independent, to relieve some of the burdens on his own men and to assist in the ongoing war against the rebel guerillas. Originally labeled as a Franco-Mexican army it soon became the full fledged Mexican Imperial Army and consisted of regular army troops, auxiliary forces to augment the regulars and the rural militia. |

|

|

At its inception in October of 1863 the Mexican Imperial Army was comprised of six battalions of infantry, six squadrons of cavalry, one scout squadron, one artillery company and an invalid corps in the regular army with came to a total of 7,000 men. In the auxiliary forces were ten infantry battalions, twelve cavalry squadrons, a battery of field artillery, a section of mountain howitzers, a total of 3,800 men and some 2,300 addition auxiliary forces in eleven smaller units. A regiment of Imperial Guards was also authorized and in the process of forming at that time. The army grew fast and by the summer of 64 the Mexican Imperial Army had grown to 19,437 men. By the following year (1865) Emperor Maximilian had his own general staff and reorganized his army which consisted of 12 infantry battalions of the line, 2 light infantry battalions (cazadores), 6 cavalry regiments, 12 companies of presidial cavalry, 1 battalion of field artillery consisting of six batteries, 1 artillery regiment of 4 mountain batteries and 4 batteries of horse artillery, a corps of engineers with a battalion of the elite sappers (zapadores), an administrative corps of medical, supply train and other support personnel, a Gendarmerie legion and a company of the elite Palatine Guard. The official establishment for this army was 1,164 officers and 22,374 regulars. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Because of the nature of the war the Imperial Army was often not what it was supposed to be on paper. Battalions which were supposed to consist of 800 men often had less than 400 and in October of 1865 the total strength of the army was reported to be 7,658 regulars, 9,432 auxiliaries and 12,263 rural militia and gendarmeries for a total force of some 29,353 men. Obviously, the bulk of the army was aimed at police duties to combat the republican bandits and guerillas. This was a necessary reaction to the stated policy of the republicans to avoid regular battles with all French and Mexican Imperial forces and instead to focus on guerilla raids against unarmed columns and outposts. There was also, of course, the foreign contingents of volunteers from Belgium and the Austrian Empire but these were always a minority. Despite what detractors may say the overwhelming majority of the troops in the Imperial Mexican Army were Mexicans. Relations between all of these groups were not always entirely cordial though. The French were generally disdainful of the Mexicans they encountered (whether republicans or imperialists) and generally did not think well of the Belgians either. Similarly, due to recent conflicts in Europe the Austrians were not very well inclined toward the French. |

|

|

|

|

In command of this force was some very experienced and talented Mexican officers. Among the more senior generals was Juan Almonte who had served in the Texas War for Independence, as did the French General Adrian Woll who was quartermaster on that campaign. Woll has also served in the Mexican-American War and Almonte had been the Mexican envoy to the United States during the lead up to that conflict. Woll has also fought in the Reform War with General Miguel Miramon and was on the council of notables that invited Maximilian to assume the Mexican throne. He served as the Adjutant-General of the Mexican Imperial Army. Almonte served as interim Head of State for the regime before the arrival of Maximilian and later was envoy to France for the regime. Much of the organizational work for the Imperial Mexican Army was done by General Woll. He was also an envoy to France during the conflict. General Jose Mariano de Salas, who has also served in the war in Texas and had commanded one of the assault columns at the Alamo was part of the regency council which presided prior to the arrival of Maximilian. His age kept him from active service though he was still on the rolls as a general of the imperial army. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Perhaps the most prominent was General Miguel Miramon, formerly the youngest President of Mexico in history. He had lobbied in Europe for the establishment of a monarchy in Mexico and was eventually made Grand Marshal of the Imperial Army and sent to Berlin to study the latest military theories. He later returned to Mexico to command a division in the final days of the empire and took command of the infantry in the last stand of Emperor Maximilian and later was executed alongside his monarch. General Leonardo Marquez, the Tiger of Tacubaya, was a veteran of the Reform War and was given command of the Pacific coast region and later defended Mexico City before the final defeat, which he survived by taking refuge in Cuba. There was also the Indian General Tomas Mejia, another veteran of the Reform War, who commanded the northern forces of the Imperial army based out of the border city of Matamoros. He distinguished himself throughout his career both for his talent and his character. At the last stand at Queretaro he commanded the cavalry and later died alongside Miramon and his Emperor. The more junior commanders also included a number of very talented foreign officers. There was Lt. Colonel Baron Alfred Van der Smissen who led the Belgian legion, the Bohemian General Franz Graf von Thun-Hohenstein of the Austrian Corps, and there were American veterans of the Civil War there such as Prince Felix zu Salm-Salm, a colonel in the imperial army and personal adjutant to Emperor Maximilian, who was a veteran of the Union army and Major General John B. Magruder of Virginia who was a veteran of the Confederate army and did some of the first surveying in Mexico during his service with the imperial army. A number of other prominent Confederate generals came to Mexico to serve Maximilian but served in a private capacity while others were ordinary soldiers who volunteered for service with the army. General Magruder, like most others, was able to return to the United States but Prince Felix was taken prisoner by the Juaristas and was only released after the war thanks to the lobbying of his wife. |

|

|

|

|

When it became clear that the French army wound abandon Mexico, Emperor Maximilian had to take what actions he could to strengthen his armed forces to lessen the blow of this loss. In May and June of 1866 this led to the formation of nine new light infantry battalions of 400 men each to form the basis of an elite core of the Mexican Imperial Army to make up for the departing French forces. The battalions were to be commanded by French officers and made up of French and Mexican soldiers with the veteran French being offered significant incentives to provide them to volunteer to stay in Mexico. This also coincided with the enlargement of the army to make up for the soon-to-be-gone French. By early 1867 the Mexican Imperial Army had grown, at least organizationally, to 18 infantry battalions, 9 of the new cazadore or light infantry battalions, 10 cavalry regiments (including a hussar regiment and a regiment of the Empress Guard Dragoons), an artillery corps consisting of four garrison artillery batteries and eight batteries of field artillery, a corps of engineers with 3 companies zapadores, the infantry battalion and cavalry squadron of the Municipal Guard of Mexico City and finally the Gendarmerie and the Palace Guard. However, it must also be said that Maximilian was able to induce relatively few foreign troops to stay and many of these units were well below strength with some battalions consisting of as little as 200 men. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Throughout the conflict it was the foreign contingents which were considered the best, which should not be surprising considering that their homelands ensured they were better trained, equipped and armed than any native Mexican troops could be. The Austrian units came to have the status of almost shock troops within the Mexican army and in time the uniforms of the Mexican Imperial Army came to have a very Austrian style appearance. These men were not only Austrians however as volunteers came from various parts of the Hapsburg empire. Alongside the Austrians were Hungarians, Poles and others, many of whom it was hoped would settle in Mexico. The vast majority were, of course, Catholic and they brought along troops that were famous and unique to their homelands such as the Belgian voltigeurs, Hungarian hussars, Austrian jaegers, Polish Uhlans and so on. However, not all of the foreign contingents were even European. The Bey of Egypt dispatched a battalion of 450 Sudanese troops to pacify the Veracruz region where they earned quite a ferocious reputation. There were also blacks among the French forces such as the Martinique Volunteers. All in all the Mexican Imperial Army was probably one of the most ethnically diverse armed forces in the world. Since the republican rebels with their Zapotec president liked to portray the conflict as a fight by Indian and mixed race Mexicans against wicked, European whites, Emperor Maximilian tried to counter this by displaying the diversity of his government and military. A common picture postcard featured portraits of General Miguel Miramon, a European blood Mexican; General Tomas Mejia, an Indian blood Mexican and General Ramon Mendez, a mixed race Mexican. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

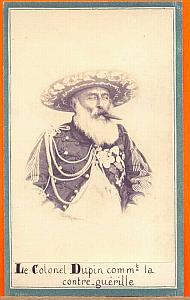

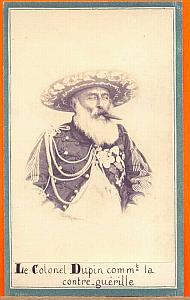

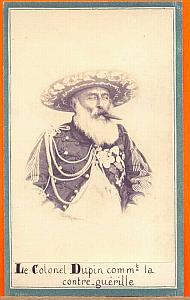

The Mexican Imperial Army was never given a very fair chance to prove itself. The pullout of the French coincided with the sending of massive amounts of money, supplies, arms, artillery and even men to the rebels from the United States and so most considered the cause of the empire to be all but lost as soon as the French troops began shipping home. Nonetheless, some units in the Mexican Imperial Army did gain a great deal of fame and sometimes notoriety among their compatriots as well as Mexico as a whole. Certainly the most colorful unit was the Palatine Guard, the palace detachment of the Imperial Guard which was commanded by Count Bombelles and had a very Teutonic appearance with their long beards, Roman helmets surmounted by crowned Mexican eagles, their large halberds and very colorful red, white and green uniforms with thigh-high boots. It should be pointed out that many conservative Mexicans complained loudly when Emperor Maximilian started putting his troops in red tunics as this was the color associated with the liberals. Another very striking unit was the Red Hussars led by Count Karl Khevenhueller-Metsch. The most infamous though was certainly the Contra-Guerillas led by the French Colonel Charles Du Pin. This was a mixed unit that even included some American volunteers and although they won few friends (in fact those captured were usually summarily executed by the republicans) they were certainly good at what they did. On the opposite side, the weakest area for the Imperial army was certainly the artillery. The French took their guns with them when they left and thanks to the US Army sending the rebels modern, rifled pieces the army of Maximilian was at a definite disadvantage and very much out-gunned at the end being armed only with some very old French and Spanish smoothbore canon. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Toward the end of the conflict, the biggest problem the army faced was desertion. In a country long famous for shifting loyalties more and more soldiers deserted (sometimes even during battle) when it seemed the republicans had the upper hand. Nonetheless, given the odds against them they performed well even up to the bitter end. It is rather amusing to see modern historians who are mostly hostile to the empire of Maximilian and downright sycophantic toward Juarez trying to understand why Maximilian had as many troops as he did at his last stand at Queretaro despite clearly being in the most desperate condition. In short, there was not much of a chance for the Mexican Imperial Army, but it certainly had a lot of excellent qualities and a great deal of potential. They struggled heroically considering the odds against them and only had victory snatched away from them due to circumstances beyond their control when they lost their French ally just as the republicans gained the US as an ally. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This picture is from "The Mexican Adventure 1861-67" by Rene Chartrand and Richard Hook. Shown are an imperial infantry soldier in a typical French supplied uniform, a soldier of the regular cavalry in campaign dress and (standing) a member of the fearsome contra-guerillas. The book is extremely biased in favor of the republicans but still very informative and contains many period photographs as well as the color plates like this one. It can be found at Amazon.com here for those interested. |

|