|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Confederados: American Rebels in Mexico |

|

|

|

Throughout the short life of the Empire of Mexico and the French intervention possibly the most critical factor in the success or failure of the whole enterprise was the outbreak of the War Between the States north of the Rio Grande. With the Monroe Doctrine the United States had effectively proclaimed all of the Americas as her domain alone and threatened war on any European nation that involved itself in the Western Hemisphere. There is little doubt that the U.S. would have rushed aid to the liberal government of Benito Juarez when the French, British and Spanish forces first landed at Veracruz were it not for the fact that the U.S. already had its hands full trying to crush the confederation of southern states that had seceded from the Union. Nonetheless, the U.S. made it clear from the beginning that they were totally opposed to the French intervention and would oppose any effort to establish a monarchy anyway in the New World. |

|

|

This was not surprising given that the U.S. had already openly sided with Benito Juarez and the liberals in the earlier Reform War against the Mexican conservatives. Most history books point out that the U.S. Congress unanimously passed a resolution condemning the establishment of a monarchy in Mexico though fewer point out that it was unanimous only among the northern congressmen as all the southerners had withdrawn by that point. In any event, there was never any doubt that though neither government had an official position the Confederates favored the French and Maximilian while the United States favored Benito Juarez. The French Emperor Louis Napoleon III had for a time flirted with recognizing the Confederacy but in the end would do nothing without British support. Once Emperor Maximilian was established in Mexico City the Confederates even approached him with a proposal for an alliance. In return for his own recognition and help in gaining that of the French as well the Confederates promised assistance in his war against the Juaristas. |

|

|

The problem was that Napoleon had lost interest in the Confederacy by that time and Emperor Maximilian, though first enthusiastic about the idea, could do little without French support. Napoleon III would later be faced with the reality that the success or failure of his intervention in Mexico was inextricably tied with the success or failure of the southern Confederacy. When the end for the Confederates came in 1865 the Mexican Emperor was obsessed with winning the good will and friendship of the United States which sometimes meant turning away offers of assistance from the defeated Confederates. It was a naïve position to take as it should have been very clear to everyone that the U.S. would never support the Mexican monarchy under any circumstances whatsoever. For instance, during the most triumphant days of the empire the U.S. continued to address with Juarez as the legitimate President of Mexico even when his government consisted of nothing more than his own carriage and a ragged handful of bodyguards fleeing through the deserts of the northern Mexico. After the assassination of Lincoln Emperor Maximilian sent a letter to President Andrew Johnson assuring him that his was a liberal and freedom-loving regime that wanted nothing but friendship with the U.S. Johnson refused to even accept the letter and soon after invited the wife of Benito Juarez (who had been in the north lobbying on his behalf) to the White House to be assured of continued American support. |

|

|

Even during the War Between the States a network of support sprang up across the United States for Juarez as Republican Clubs formed in city after city to raise support for Benito Juarez, widely regarded by the U.S. as "their man" in Mexico. Many Union generals called for an immediate invasion of Mexico to overthrow Maximilian and restore Juarez in Mexico City and several vied for the opportunity to lead the expedition. Hostilities had come close to breaking out already at the south Texas border town of Brownsville where two wars bumped heads. However, for all of the Yankees who saw Maximilian as an autocrat and the Mexican Empire as a threat to American interests, the defeated southerners saw the country as the possible opportunity for a fresh start. One of the first Confederates to go to Mexico was Commander Matthew F. Maury of the Confederate Navy. Maximilian had been a naval man and Maury was well known around the world for his work in oceanography and marine meteorology. |

|

|

The dapper and intellectual Maury made quite an impression on Emperor Maximilian who immediately appointed him to the imperial observatory and coordinator of the further immigration of Confederates to Mexico. William M. Anderson, a southern archeologist, had been inspecting Mexico just after the war with the same thought in mind. There was a great deal he found troubling about Mexico and the Mexican temperament but he also felt it held great promise for transplanting the plantation culture of the Deep South. Confederates in numbers great and small began to come to Mexico, some by sea from New Orleans and others across Texas and the Rio Grande. One of those was the Confederate cavalry brigade of General Joseph O. Shelby who buried his flags in the mud of the riverbank before crossing over and putting the question to his men as to which side they would offer their services; Benito Juarez or Emperor Maximilian. The southerners shouted for the Emperor and so Shelby went to meet the Mexican monarch with a grand proposal that he could organize 40,000 Confederate veterans to come to Mexico and fight for the empire. Maximilian was impressed by General Shelby but reluctant to risk worsening relations with the U.S. and so refused the offer of military support. |

|

|

More Confederates streamed into Mexico and the capital city. Former generals and dignitaries Edmund Kirby-Smith, Sterling Price, Alexander W. Terrell, Isham Harris, Jubal Early, Richard Ewell and Simon Bolivar Buckner all came south. General Robert E. Lee was cordially invited but refused to leave his beloved Virginia and recommended against former Confederates moving to Mexico and Brazil as many were doing. One who particularly caught the eye of the Mexican Emperor and Empress was General John B. Magruder, known as Prince John for his elaborate style and dapper mannerisms. The theatric Confederate was an instant favorite at court and soon became a trend-setter. When his appearance and clothing was commented on so favorably he advised other Confederates to follow his example and soon Emperor Maximilian himself was dressing in the style made fashionable by Magruder. Soon he was given the rank of general with a staff position in the Mexican Imperial Army. Most of the Confederates, however, settled down to civilian life and when not enjoying life at court in Mexico City concentrated on the establishment of their colony of Carlota in Veracruz near the town of Cordoba. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

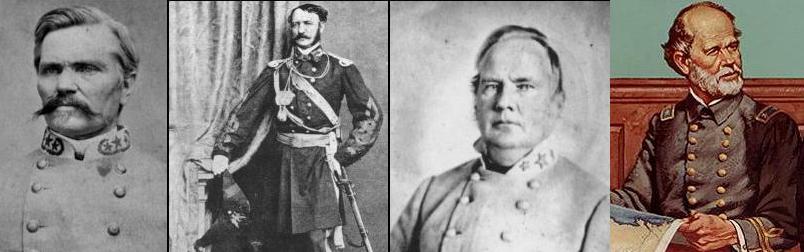

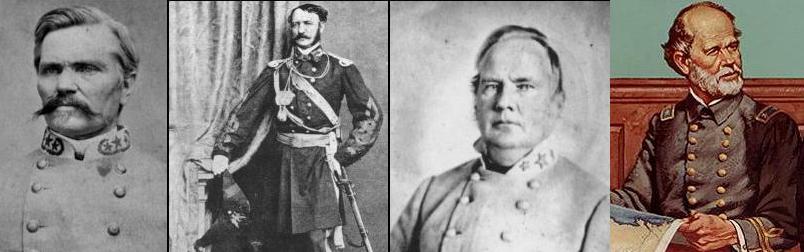

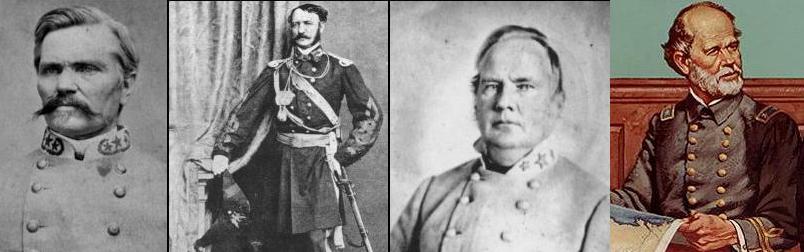

Generals Simon B. Buckner, John B. Magruder, Sterling Price and Commander Matthew F. Maury |

|

|

|

This was to be a sore subject for many enemies of the empire in Mexico as the land Maximilian granted the Confederates was some that Juarez had previously confiscated from the Catholic Church. One of the stipulations for the Confederate settlement was the guarantee of freedom of religion for the mostly Protestant Confederates. Maximilian had always favored freedom of religion alongside the recognition of Catholicism as the official religion of the empire, but it was a stumbling block in relations between Maximilian and the Catholic Church which refused to full endorse his regime until he forbid toleration of all but the Catholic faith. The Juaristas were angered at Mexican land being occupied by Americans of any sort (forgetting that Juarez himself had sold out vast tracts of Mexican land and sovereignty to the U.S. for four million dollars) and the Church was always opposed to anything but the full return of all of their lands and the establishment of Catholicism to the exclusion of all other religions. The Confederates themselves, however, were very hopeful at the outset of this new enterprise; perhaps not surprising given what they had so recently been forced to go through. |

|

|

Brigadier General James E. Slaughter, the commander of Confederate forces on the south Texas-Mexico border at the end of the war had a vision of transferring all his forces south of the border, joining with Maximilian to defeat Juarez and the republicans and then returning north with a combined French-Mexican-Confederate army to restore the southern nation but, of course, nothing came of the grandiose plan. The Confederates concentrated on their land in Veracruz on 640 acre lots where they began planting cotton, coffee, sugar and tropical fruits while constantly having to fight off attacks by republican bandits and guerillas. There were grand visions of places called New Virginia to be grown up around the colony of Carlota which Confederate settlers told visitors proudly was named for the lovely Belgian Empress for whom, it was said, every chivalric southerner loved and was ready to shed his blood in defense of. An English language newspaper was established with the patronage of Maximilian and a law office was opened up as the southerners looked toward the future. Yet, at the same time the hard fighting Yankee General Philip Sheridan was moving toward the south Texas border with his 50,000 man Army of Observation to intimidate the French and cut off the flow of southern settlers to Mexico. US General John Schofield, who had lobbied for an immediate invasion and march on Mexico City was sent to Paris to put pressure on Napoleon III there. |

|

|

The Confederates at the glittering receptions in Mexico City, setting themselves up in the hotel that had once been the palace of Emperor Agustin and working their humble settlement in Carlota did not look like much but they were a major concern for the United States. The Yankee elites feared that if the Confederates took root and prospered they might one day cross the border again in alliance with a strong Mexican Empire and fight to restore their defeated Confederacy. The U.S, quickly put pressure on the French to leave Mexico entirely and with their loss and the large force of Americans across the border giving support to Juarez and threatening to intervene themselves it seemed to many that the days of the Mexican Empire were surely numbered. The old Missouri General Sterling Price might have boasted that he was growing tobacco superior to that of Cuba, but their fate was tied to the throne of Maximilian as Juarez, the loyal lap dog of the United States, would not tolerate their presence if he emerged victorious in the war against the empire. With the U.S. so obviously belligerent Emperor Maximilian turned to Commander Maury to prepare a report on the populace as he was always concerned most with being loved by his Mexican people. |

|

|

In October and November of 1865 Maury honestly reported to Maximilian that his future did not look bright if his entire hopes were placed in the hands of the Mexican public. His findings were that the people were discontented with the government, that greedy ministers were ruining his image with the people and that the Church was hailing anyone killed by imperial forces as a martyr since Maximilian had refused to give in to all the demands of the Church for the restoration of all of their property and an end to religious freedom. Commander Maury advised Maximilian that his only hope was to become an iron-fisted military caudillo in the traditional Mexican fashion but this went against the character of the Emperor. Slowly, but critically, as the French pulled out of the country so did more and more of the Confederate settlers who decided that they might as well live under Yankee rule at home than leave themselves open to the hatred of the Yankee allied Mexican republicans who seemed certain to succeed with the French on their way out and the Union army gathering strength on the border to ensure the defeat of Maximilian. |

|

|

Maximilian, however, always appreciated honesty and held no anger on Maury for telling him the truth. In fact, he was just as appreciative of an even more brutally honest assessment from one Confederate who stayed on quite a while after things were obviously going against the Emperor and that was the fiery General Joe Shelby. When the situation seemed hopeless, and when it was clearly too late, Maximilian summoned Shelby to judge the possibility of the former Confederates becoming a core of military support for his crumbling empire. General Shelby liked and admired the Emperor but held nothing back. He told Maximilian plainly that he would need far more troops at that point than the defeated Confederates could ever dream of providing. The enemy had him outmatched in every way and his meager Mexican imperial forces were of dubious loyalty. In short, his situation seemed all but hopeless if not that. In that instance, yet again, Maximilian showed his appreciation and remarked that he thought those words of Shelby were some of the first honest words he had heard in quite a while. With nothing else to give him, Maximilian took off his Order of Our Lady of Guadalupe and gave it to General Shelby for being such a faithful friend to the end. Not long after the doomed monarch went on to his last stand at Queretaro while the Confederates mostly drifted back to their defeated country at home in the face of increasing Juarista attacks and raids on their colony. |

|

|

If anyone truly benefited from American aid it was Benito Juarez. In all, about 3,000 Americans served in his army; almost entirely from the northern states that had favored his cause from day one. Juarez also benefited immensely from military, material and diplomatic aid from the United States. Not only did the U.S. force France to abandon Mexico and keep Austria from sending reinforcements to their volunteer corps they also sent Juarez arms, ammunition, supplies and clothing to the extent that he had far superior weaponry to Maximilian in the final campaign. Many Mexican soldiers went into battle for Juarez wearing complete U.S. army uniforms and with U.S. army rifles and equipment. They had a distinct advantage in their possession of rifled artillery from the U.S. and the innovative Henry repeating rifles given by the U.S. to the Mexican republicans. It seems odd that the most celebrated president in Mexican history, Benito Juarez, owes his success so much to the assistance of the United States which so many Mexicans have always viewed as their mortal enemy from start to finish. It seems tempting to believe that if a little deeper thought were put into the issue a greater truth might be revealed by that fact as to who actually had the potential to make Mexico a stronger and more stable country. |

|

|

As for the Confederates, it would seem to some that they were driven almost like moths to a flame to lost causes; perhaps the legacy of the Jacobites as others have theorized. Of all those who fled the land Dixie those who migrated to Brazil probably fared the best, but even there the Empire they came to serve was not destined to long survive. For those who put their hopes in Mexico the dream was even more short-lived. The Old World style of the country appealed to them as did their sense of chivalry in defending the Empress Carlota, but by the end the Empress was gone and they were surrounding by hostility and faced with yet another lost cause and, as appealing as that might have been to their romantic nature, they were Americans after all and losing one war was more than enough for most of them. In addition there was the blood and soil argument and as dazzling as the dream of rebirth in Mexico might have been they were still attached to the ancestral homeland of the Deep South that was calling them back in that darkest hour. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

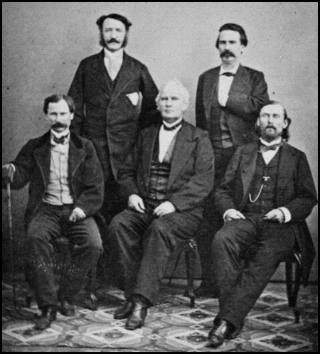

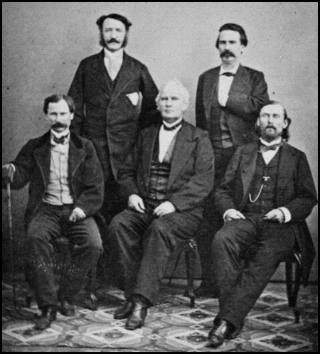

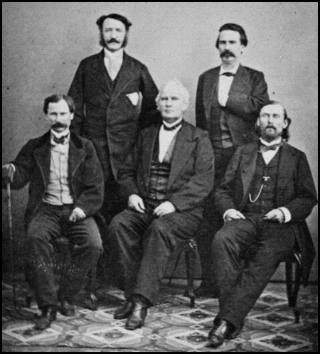

Confederates in Mexico (left to right) Isham Harris, John Magruder, Sterling Price, Joe Shelby and Thomas Hindman |

|