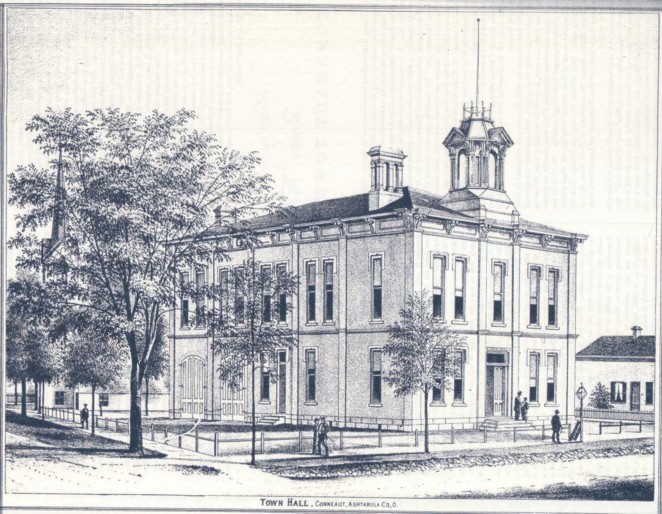

Town Hall - Click on Thumbnails for larger images

[155] size, and evidently belonged to a race allied to giants. Skulls were taken from these mounds, the cavities of which were of sufficient capacity to admit the head of an ordinary man, and jaw-bones that might be fitted over the face with equal facility. The bones of the upper and lower extremities were of corresponding size."

The imagination is pained in endeavoring to penetrate the mystery in which the history of this people is shrouded. That the multitude whose mortal remains people these receptacles of the dead once existed, that they were members of the human family, that they died and were buried, is incontrovertible; but what was their origin, what their language, what their habits, their religion, and their moral, political, and social condition, -- all this remains an insoluble mystery.

These ancient people were succeeded by various tribes of Indians. The first of these known to the white settlers were those inhabiting this region at the time of the arrival of white immigration in 1796-97, said to be a remnant of the Massasaugua tribe, dwelling on the present town site of the village of Conneaut, under a chief by the name of Macqua Medah, or "Bear's Oil." This warrior's village consisted, at that time, of some thirty or forty cabins, inhabited by as many separate families. They were a feeble people, unable to offer successful resistance to the encroachments of the whites, and very soon retired from their pleasant hunting grounds on the banks of the Conneaut. Their cabins were rude structures, about twelve or fifteen feet in height, formed of logs, with bark for roofs, but presented an appearance of neatness and comfort seldom observed among the Indians. Here was their council-house, and here their king's palace, which the settlers, with little respect for the dignity and sanctity with which they were undoubtedly associated in the minds of these red children of the woods, converted the one into a barn and the other into a poultry-house. When the Indians were about to abandon the country, their chieftain, in a very threatening manner, warned the whites against ever trespassing upon a certain spot of ground, declaring that if they did not respect his wishes he would return and scalp the inhabitants "as far as he could pole a canoe up the creek." This spot, so sacred to the Indian king and his people, contained the grave of his mother, and was designated by a square post some eight or ten feet high, painted red, and sunk into the ground, and stood on the margin of the creek, near where the present iron bridge now crosses the stream, east of the village. The lands between the post and the mouth of the creek were the "consecrated spot." The settlers paid little or no attention to this demand.

The immediate cause of the expulsion of "Bear's Oil" and his tribe from Conneaut was a murder committed by one of his party of a white man whose name was Williams. This individual, about the year 1797-98, in traveling from Detroit to Presque Isle, or Erie, had sold an Indian a rifle, for which he agreed to trust him for a specified time, and receive his pay in peltries. After the delivery of the rifle, Bear's Oil, either from motives of friendship or from a desire to involve Williams in difficulty, told him that the Indian was bad, and that he would not get his pay. Thereupon Williams went to the Indian, demanded the return of his rifle, and compelled him to give it up. Incensed at this procedure; on Williams leaving the village, the Indian waylaid his path as he was passing down the beach and shot him, a few miles below the mouth of the Conneaut, and again possessed himself of the rifle. As soon as the circumstance was known to the commanding officer of the military post at Presque Isle, he sent to Bear's Oil, demanding the murderer. Bear's Oil, after some hesitation, agreed that if an officer and a suitable number as guard were sent forward to take charge of the prisoner, he would give him up. On the arrival of the guard, they were invited by Bear's Oil to remain until morning. The invitation was accepted, and when morning came they were gravely informed by the chief that they had deliberated upon the matter, and had decided not to yield up the murderer; at the same time making a show of his force, which consisted of thirty or forty braves, armed and painted in a warlike manner. The guard, unable to contend with so large a force, retired to their bateau, which had been left at the head of the deadwater, and descended the creek, not, however, without apprehension of a salute from the Indians' rifles as they passed some of the close thickets which covered the shore. No interruption of the kind, however, occurred, and they returned with all possible expedition to Presque Isle.

Upon the receipt of the intelligence the troops at the garrison, with as many volunteers as could be suddenly collected, were embarked in boats, with orders to proceed to Conneaut, secure the murderer, and to inflict such chastisement upon the whole party as the nature of the case demanded. But arrived at the anticipated scene of action they found the village deserted. The enemy had fled and left them nothing upon which to expend their valor. No war-cry greeted their ears. Old Macqua Medah understood the nature of the call that was likely to be made upon him, and had launched his canoes and paddled them up the lake as far as Sandusky.

Thus disappeared, never again to return, Bear's Oil and his people. It is said that he located on the Wabash.

The ruins of a more ancient village, said to have belonged to a remnant of a tribe of Seneca Indians, were yet remaining at the time the first settlers arrived. This village was located on the east bank of the creek, near the Harmon farm. There were evidences of the ground having been cultivated, and an apple-tree was found here in a thrifty condition. They probably lived here as late as the time of the treaty of Greenville, in 1794. They had been engaged in the Indian war so disastrous to the white settlers, when General Harmon, in 1790, and Governor St. Clair, in 1791, led the armies of the Ohio settlers against the red men and were sorely defeated. At St. Clair's defeat on the Miami, November 4, 1791, two young men were taken prisoners by this band of Indians and were brought to this locality. They were without doubt the first white men that looked upon this region, and were captives for a number of years. The name of one of these individuals was Edmund Fitz Jeralds, but that of the other cannot be ascertained. They were among the number that survived the slaughter on the Miami, when the Americans were defeated by the savages with the loss of more than six hundred of the militia. They were at first a part of a large company of prisoners, but as the different tribes marched homeward and began to separate, each clan, as its share of booty, took a number of the prisoners, and Fitz Jeralds and his companion became the spoil of this Seneca tribe, and thus were brought to the banks of the Conneaut. Their arrival was celebrated by the customary practices adopted by the Indians upon like occasions. The prisoners were made to run the gauntlet, to receive the requisite number of kicks and blows, and to listen to the taunts and jeers of their captors. The moment of supreme solicitude, however, arrived when the braves assembled in solemn council to decide what should be done with the prisoners. Would the sentence be death? and if so, would it be death from the tomahawk, or death from the rifle, or death at the stake? It was a moment of fearful suspense. Soon the decision was announced. One was to die, the other to be spared. Fitz Jeralds was the fortunate one. His companion was doomed to die. The youthful Indian warriors must needs be taught the art of torturing an enemy. They must be instructed in the character of that fierce cruelty necessary to be employed in dealing with a foe whom they hated. Fitz Jerald's companion was sentenced to be burned. A red-oak tree was selected, and certain significant signs rudely carved upon it, so that ever afterwards it should be a living witness to the young warriors of the scene of cruelty about to be enacted. There appeared upon the bark of the tree the figure of a tomahawk, and that of a scalp. To this tree the young man was firmly bound. A large quantity of hickory bark was collected, tied up in fagots, and placed around him. The young man's distress was beyond all expression; that of Fitz Jeralds was from sympathy nearly as great, and yet he dared not speak or he too might become a victim to their cruelty. Would nothing happen to release the young man from the fate awaiting him? Would no one plead for him, or even beseech them to shoot him instead of burning him to death? Yes. There appears upon the scene a young maiden squaw whose heart was stricken with sympathy and grief, and, like Pocahontas, she earnestly plead for the life of the young victim. Her entreaties were heeded, and Fitz Jeralds' companion was rescued from a frightful death.

The young man became a favorite with the Indians, and soon was intrusted with important matters of business, and was employed as their agent in trafficking with the whites. In the course of a few years he was sent to Detroit with a quantity of furs to be exchanged for needed supplies, and improved the opportunity to make good his escape. He returned to Conneaut in the year 1800, and himself related the circumstances herein given, and pointed out the very tree to which he had been bound, whereon were plainly to be seen the significant signs the Indians had cut upon it.

Fitz Jeralds remained in captivity. He assisted in cultivating the soil with a wooden hoe, and in guarding the fields of maize from destruction by animals. How long he remained with the Indians is not known; but after the whites arrived he became a citizen of this county and resided here many years.

An individual by the name of Halsted was found residing here at the time the surveyors arrived in 1796, and from his own statement had then lived here upwards of three or four years. He therefore came here shortly after the arrival of the two Indian captives, Fitz Jeralds and his companion. He was discovered by the surveying party who, in running the meridian lines from the base of the Western Reserve to the lake-shore, were guided to his retreat by the sound of his axe. His cabin was situated in East Conneaut, on the farm known as the Baldwin farm, about one-fourth mile from the State line, and one mile to the south of the Ridge road. A strange life did this man lead, and some strange influence had brought him hither. He showed little inclination to be interrogated, [156] and but little information could be obtained from him. He stated that he was a native of the Old Bay State, and had lived here a number of years, subsisting by hunting and fishing, and by cultivating a few vegetables on a patch he had cleared around his hut. But of the particulars of his own history, and of the motives that had induced him to undergo this voluntary banishment from home, kindred, and friends, and to make the deep forest, infested with wild animals and wandering bands of Indians, his chosen abode, he refused to furnish any account. Perhaps he had become disgusted with the inconstancy of human friendship; perhaps he was a criminal who had escaped from the legal consequences of his guilt; perhaps it was "unrequited love" such were the explanations which conjecture could furnish, but the lips of the man himself refused to open. He manifested evident displeasure at the presence of the surveyors, whom he recognized as the advance-guard of a multitude of followers who were destined to people the land. He had supposed he had found a retreat secure from the approach of the white man, and fully intended, without doubt, to spend here the remainder of his days solitary and alone. He had girdled or deadened the timber on a few acres adjoining his cabin with the evident design of making a permanent improvement; but now he abandoned the undertaking, and quitting his cabin he disappeared from the country to seek for some more congenial locality.

The next event of importance in the history of the township is the arrival of the party of surveyors on the banks of the Conneaut, July 4, 1796. An account of this occurrence will be found in another department of this work, and hence we make but a casual allusion to it here.

At Buffalo the party halted for the purpose of holding a conference with the Indians, remnants of tribes belonging to the once great and powerful Iroquois nation, who, notwithstanding the treaty of Greenville, by which the western band had surrendered all claim to the territory, still maintained that this tract of right belonged to them. An interview for the purpose, if possible, of conciliating them was therefore held, the leader of the expedition, who acted as agent for the party, being dressed in scarlet broadcloth, for the purpose of enhancing his consequence and producing on the minds of the Indians an imposing effect. Brant, an Indian warrior and chief of one of the tribes, insisted that he and his people had claims upon the land in question, and that it would be unsafe to enter upon them until those claims had been satisfied, insisting that the western tribes had no right to sign away the inheritance of his people. Fearing to dispute the point, the agent assured him that his claims should have the recognition, they deserved, and thus, with the distribution of a few presents, were the Indians conciliated.

When the party arrived at Conneaut they pitched their tents on the east side of the creek in a beautiful grove of young maples and other forest-trees which occupied the space between the high bank and the water's edge, a spot well remembered by the early settlers, but which has long since disappeared by reason of the encroachments of the lake. Upon this same spot, and on ground since covered by the waters of Lake Erie, they afterwards erected a substantial log building, about thirty-five feet in length by twenty in width, designed as a residence, and as a depository for their stores. It is said to have been fitted up with a reasonable attention to convenience, having a well-shingled roof, and the floors, partitions, doors, etc., made from boards sawed out by a whip-saw. This was the first building, with the exception of the hermit's little cabin, a rude structure, erected by the white man upon the soil of the Western Reserve. The surveyors, after thus arranging for their comfort during their stay in this locality, proceeded to the southern boundary of the Reserve and began their labors.

James Kingsbury, afterwards known as Judge Kingsbury, arrived at the mouth of Conneaut creek shortly after the surveyors had come; and as the surveyors, in the prosecution of their work, receded further and farther to the westward, they soon abandoned the building they had erected on Conneaut creek as a place of rendezvous, and removed their stores to the mouth of Cuyahoga river, where they thenceforward made their headquarters. The commodious building thus abandoned became the dwelling-place of Mr. Kingsbury and his family, who continued to occupy it through the severe winter months that followed. As this was in the year 1796-97, it is thought that Mr. Kingsbury's family was the first that passed this winter on the soil of New Connecticut. In relation to the sufferings of this family, we make the following quotation from the well-written narrative of Harvey Nettleton, Esq., to whom we are indebted for many of the facts given in this history:

"The story of the sufferings of this family during that severe winter has often been told; but by those who are in the midst of plenty, and to whom want has never been known, it is with difficulty appreciated. "Circumstances rendering it necessary during the fall for Mr.-Kingsbury to make a journey to the State of New York, he left his family in expectation of a speedy return, but in his absence was prostrated with a severe attack of sickness that confined him to his bed until the setting in of winter. As soon as he was able he began to return, and proceeded as far as to Buffalo, where he obtained an Indian guide to conduct him through the wilderness. At Presque Isle, anticipating the wants of his family, he purchased twenty pounds of flour, and continued his journey. In crossing Elk creek on the ice he disabled his horse, left him in the snow, and placing the flour upon his own back, pursued his way, filled with gloomy forebodings as to the condition of his little family. On his arrival, late in the evening, his worst apprehensions were more than realized in the agonizing scene that met his eyes. Stretched upon the cot lay the partner of his cares, who had followed him through all the dangers and hardships of the wilderness without repining, pale and emaciated, reduced by fierce famine to the last stages in which life can be sustained, and near the mother, on a little pallet, were the remains of his youngest child, born in his absence, and who had just expired from the want of that nourishment which the mother, herself deprived of sustenance, could not supply. Shut up by a gloomy wilderness, far distant from the aid and sympathy of friends, filled with anxiety for an absent husband, suffering with want, destitute of necessary assistance, she was compelled to behold two children expire around her, powerless to help them. Such is the picture presented, truthful in every respect, for the contemplation of the wives and daughters of to-day, who have no adequate conception of the hardships endured by the pioneers of this beautiful country of ours. "It appears that Judge Kingsbury, in order to supply the wants of his family, was under the necessity of transporting his provisions from the mouth of the Cuyahoga on a hand-sled, and that he and his hired man drew a barrel of beef the whole distance at a single load."

Mr. Kingsbury became prominently connected with the history of the Reserve, and was honored with several important judicial and legislative trusts. He soon removed from Conneaut, and finally settled in Newburg.