That's me, on day 9, just off the Baird Glacier. Photo by Chiu Liang Kuo.

That's me, on day 9, just off the Baird Glacier. Photo by Chiu Liang Kuo.

I had climbed for 11 years and with Chiu Liang Kuo for the past four years: we'd had many adventures together -- good and bad -- and they led Chiu and I to decide on an attempt on the Devil's Thumb, in southeast Alaska. My vision was of a bold, self-supported expedition in which we would manhaul in all our food and equipment, rejecting the helicopter transport to base camp used by most parties, and even the airdrops of supplies. We were to be the first totally self-supported expedition up the Baird Glacier, with the goal of climbing the Thumb and then returning under our own power, in well over a decade. The two months leading up to the start of the expedition were a period of almost unbearable stress, as I juggled my MA thesis, work, expedition planning, and making arrangements to move out of my apartment, put all my possessions in storage and sink every penny I could into the endeavor. Chiu did much of the planning, but in the last week I turned in a good advance copy of my thesis and finally was able to turn my attention to the trip.

With two, 100-lb sledges, skis, poles, sledge traces, and a backpack each, we flew from Seattle to Petersburg, Alaska, at one point on the flight actually seeing the Devil's Thumb jutting up through the clouds...the only peak visible.... Amazing. In Petersburg we chartered a bush plane to drop us at the foot of the Baird Glacier, then spent two days finalizing our plans and buying last bits of gear and supplies. We rented a small Marine Band radio as a measure of safety. Finally we loaded up the plane and as we lifted off from the airstrip in perfect weather I had a hard time believing we were actually going to do it...

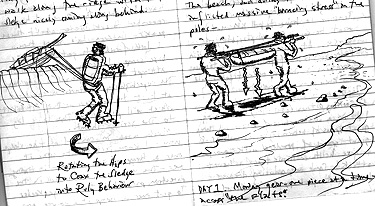

Forty minutes after leaving the airstrip, Chiu and I stood on the beach beneath the Baird Glacier and watched our plane skim up off the water and disappear behind a mountain. We were now alone and committed to our goal. We spent the first day carrying our 100-lb sledges, 35lb-packs, and the skis and poles, across the 2-mile long beach to the true glacier foot. This took several trips, summing to about 8 miles of hard work that day.

We set up our lightweight, floorless Megamid tent on the beach just under the glacier, hoping it would not give way with one of its famous, enormous flood episodes (which would blast us away without trace, no sweat), and turned in. A light rain that evening loosened rocks on the slope behind us, but I believed they could not roll down to us because of the deep sand, so I just turned my head to the tent entrance and went to sleep. Chiu was concerned about the rain creating a stream which could invade our camp, but again I did not consider this a problem; I thought it would take a much heavier storm to divert water from the already well-established streams...Anyway, the night passed without problems, except for Chiu's case of diarrhoea, and we woke to grayish skies.

For the next four days we navigated a difficult and dangerous passage through the worst of the crevasses on the Baird Glacier, making roughly 5 miles total, primarily because we had to carry the sledges much of the time.

One man would hike ahead and scout the way, then return, then both would carry one sledge ahead perhaps two hundred meters, heaving, pulling, pushing, dragging, sliding, levering and willing the dead-weight sledge across crevasses, up steep slopes of ice, and so on. Tough work, always in crampons, always wearing the 30-lb pack which was beginning to feel like a permanent growth on my spine. Once one sledge was moved, we'd go back for the other sledge and repeat the process. For each 1-mile day, we probably did 5 miles or more in back-tracking. Our ice camps were tolerable and food was plentiful. Hard work, but it felt great to be out there, alone, pulling, doing something unusual.... We were on the way...

On the fifth day we finally emerged from the worst of the crevasses, slightly descending to large, open rather flat expanses we called 'the Superhighway'; on this day we traveled further in one day as in the past four combined! It was a real blessing, and I could see that things were going well, we were going to make it. We traveled separately on the superhighway, taking our own pace. Weather was as it had been for the last week: unsettled, with some wind, a bit of freezing rain, but nothing intolerable. We established a camp very early that day, around 5pm, though I thought we should take advantage of the perfect terrain and unbelievably sunny weather; I thought we should go on until 9pm, just when it began to get towards dusk. However, Chiu felt for some reason that we should call it a day, and at 5pm we camped and cooked and turned in, now very easy with the routine and feeling comfortable with everything. This was right, and we had a good chance, I thought.

The next morning Chiu said he wanted to go back. I was astonunded, aghast and shattered. Appparently he'd had a close call the day before, with one of the last crevasses; his sledge had got out of control and nearly pulled him into a melt-water river. Trying to get the sledge out of the water, he'd nearly fallen into another crevasse. Since we were traveling separately, I had seen nothing. I had expected that if I could get past a crevasse without trouble, so could Chiu, so we took our own pace. Chiu was angry that morning, and the night before, that I'd been too far ahead. I reasoned, again, that the terrain had been OK, nothing compared to the previous days, and I pointed out that we had agreed to take our own pace on the flats. We sat there in the tent bantering back and forth and, though it was crazy, I tried to convince him to go on; but you cannot convince someone to do this sort of thing; they have to want it, or even need it, as much as you do. Chiu also said that I was taking too many chances, that I was driving him nuts with my less-than-precise ways...I responded that although I was not as meticulous as he was, I achieved the same results.

I said that, of COURSE I was driving him nuts, to some extent...he was driving me a bit nuts too (what more can you expect, living in a stressful situation for days on end with one partner), but I considered that a simple reflection of different personalities, that it was *unimportant*, that our common goal was much more important, and that we could continue on as we had many times before...this was our greatest chance, our most ambitious voyage -- I just couldn't go back without trying to change his mind. Chiu then said I'd been too dangerous for a long time, and I finally got angry as he told me he didn't trust my belay technique, that I was always too dangerous on climbs. I couldn't believe it. Why didn't he tell me this a year ago? Or a month ago? Why go on an expedition with someone you didn't trust? Just that day I had been thinking how fantastic it was that we were a team with total trust in one another, that Chiu and I had been through so much -- storms, bad descents, rotten conditions -- that we were a fantastic team...and now he was saying he did not trust me...It was like a knife in the back. How long had he not trusted me? What the hell was going on? First he said it was the crevasse incident, now that he didn't trust me in the mountains...it all combined to make him want to get the hell out of there, I guess.

We just sat there for a while. Finally, I asked what he wanted to do -- it was all up to him. He pointed down the glacier and said "That way. Sorry." I just couldn't believe it. We took off, headed down the glacier, another dream wrecked. I was so enfuriated that I probably said no more than 20 words to Chiu over the next four days of descent down the glacier. For two and a half days and three nights of sheer misery we just lay in the tent during a rotten storm with sleet, rain, mist and snow, eating no hot food, just dried beef, cookies, nuts and chocolate. There was nothing to say and I just continued to think about how Chiu could go on this trip in the first place if he didn't trust me in the mountains....it made no sense, unless here things were just more amplified than ever before; this was a dangerous expedition, the most dangerous thing we'd ever tried...I felt it was dangerous, and I too had had close calls, but I took it all as part of the expedition. Expeditions were dangerous, no matter who went on them. The best climbers still died from 'average' mistakes, or even objective dangers...What would Chiu do in Greenland, our next plan? The danger there would be ten times this...I couldn't think about it. I read my book, studied the velcro of my watchband, counted threads in my sleeping bag, looked at bits of feather that escaped the bag, read my book again....awfully boring. Finally we woke to decent weather, then headed down the glacier again, soon in a light rain which made things absolutely miserable. I'd never been in a worse mood. We finally reached the beach, on the ninth day of the expedition.

We built a campfire from driftwood and I began to anticipate the beer I'd have back in Petersburg. If we were going to get out of there, we may as well do it as soon as we could; all I cared about now was getting to the bar. After three days of not talking, Chiu and I finally sat around the fire and started dissecting the failure of our expedition. To my immense relief he mentioned that he'd been pretty angry at me, and that what he had said about not trusting me was an exaggeration. Since my self-identity is rooted in climbing, and since we were supposed to trust each other completely at this point in our partnership, having him say he could not trust me was the worst insult I'd ever experienced, and now at least I found it was not true. Although we climbed at the same level, I was not always as safety-conscious as Chiu...that was the way he saw it. I had seen him, however, do dangerous things I would never do, but in my mind, we did things our own way but together we overcame obstacles. On this trip, too many negative energies combined in Chiu's mind; his relationship with his wife (being destroyed by climbing), the close encounter with death at the crevasse and the meltwater stream, apprehension about my safety in the mountains. He wanted to go back, so of course this is what we did. Hearing that he did not actually think I was a completely reckless idiot relieved me incredibly. Finally, we were able to joke again. The horrible tension was broken by simple communication. I was able to smile and think about that cold beer. What the hell...we'd had a shot at it. Importantly for my ego, I reminded myself that I was not the one who'd decided to call it off...

That night we saw a small boat in the bay, and I immediately got on the radio. Expecting good weather the next day, we did not ask for assistance. The next morning we built a fire and sat back to watch for boats in the strait beyond Thomas Bay. On the radio we could hear quite a bit of traffic, but no-one could hear us. We tried to contact the Marine Operator...nothing. Pacific Wing, our bush-plane charter, didn't reply, nor did the Petersburg Harbormaster. We walked miles on the beach to find a better position to transmit, but still nothing, and we cursed the little radio...We began to think of how long we might be stranded...perhaps 20 days, until the plane came, as we had arranged back in Petersburg? We sat at the campfire and, quietly, quit eating the supplies we'd been eating so much of for the past few days...we might be there for some time...

At one point Chiu went off for more firewood, and I suddenly spotted a small motorboat zipping across the bay, about five miles away. I jumped into the tent, grabbed the radio and tried to contact the boat. Finally the skipper replied. Chiu was back at the camp by this time; he told me I'd finally get that beer. The boat's skipper relayed our request for pickup to the Harbormaster, who contacted Pacific Wing, who said they would reach us in about two hours. Suddenly it was all over. We broke camp, dragged our sledges across the beach and sat on the point, waiting for the plane.

plane. Three hours later we were back in Petersburg, and an hour after than, in Kito's Kave, devouring double portions of Mexican food...the cold beer was probably the best I'd ever had, and it washed down 10 days of hardship with the first gulp.

Now, back in Portland, I am desperate, depressed, unfulfilled and flat broke, living in a 12-by-12-foot apartment and back at my old job in the computer lab. Coming back a month early wrecked so many detailed plans that it is hard to think about...all my savings are gone, I can't work as much as I need to, all my books are in storage.... Finishing my thesis was, according to my plan, supposed to lead to another triumph, one for the non-academic half of my life. Though Chiu and I were still alive, which is definitely success at one very important level, I did not get the ascent that I need after all these years of preparation, the experience that I crave. Chiu will go back to Taiwan pretty soon, so I am now just working, waiting, saving $$$ and planning for a trip to the Bugaboos, or Yosemite, to climb something which will give me the challenge I need. I will go with McRee, a young traditional climber I met last term. He seems solid, and I hope to find we can climb together for a long time. As for Chiu and I, we may be able to rope up for other ascents when he comes back to the States for his PhD, or even for other expeditions later on. We'll have to wait and see what we feel like after some time has passed.

NOTE: October 1997. The expedition is something I still think about at least once a day. I have GOT to go back there, and have another shot at this amazing adventure. I am beginning to plan again...