Travels in the Morea

By William Martin Leake, published at London in 1830.

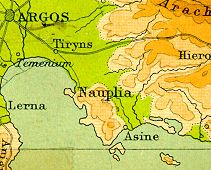

Volume I, Chapter XIX, pages 356-363. Nauplio.

[Previous - Tiryns] ...I return to

Tiryns; leave it at 4.47, and at 5.27 enter the gate of Anapli. A

pleasant kiosk, belonging to an aga of Anapli, is curiously situated on

the side of the rock to the left entering the fortress. A little

beyond it is a cavern, which was, perhaps, one of those mentioned by Strabo

as containing works of the Cyclopes.

[Previous - Tiryns] ...I return to

Tiryns; leave it at 4.47, and at 5.27 enter the gate of Anapli. A

pleasant kiosk, belonging to an aga of Anapli, is curiously situated on

the side of the rock to the left entering the fortress. A little

beyond it is a cavern, which was, perhaps, one of those mentioned by Strabo

as containing works of the Cyclopes.

Nauplia seems never to have

attained, in ancient times, an importance equal to that which it acquired

during the Byzantine empire, and which was even augmented when it became

the chief town of the Morea under the Venetians and the Turks. As

its name is not mentioned by Homer, and very rarely occurs in the history

of Greece, it was probably never any thing more than the naval fortress

or arsenal of Argos. This was its condition in the time of Strabo;

in that of Pausanias the place was deserted. He remarked only the

ruins of the walls, a temple of Neptune, the source of water called Canathus,

and certain ports, by which he meant, probably, such artificial basins

as the ancients were in the habit of employing. He observed also

the figure of an ass upon a rock, which had been placed there in memory

of the origin of the pruning of vines:-a vine which had been cropped by

an ass having been found to produce grapes much more plentifully than any

others. During the time of the Greek empire, the name “he Nauplia”

assumed the form “to Nauplion” or “to Anaplion,” or the same words in the

plural number. The bishop of Argos is still entitled bishop of Anaplia

and Argos.

The modern town stands upon

the north-eastern side of a height, with a tabular summit, which projects

from a steep ridge at the south-eastern angle of the bay of Argos.

This height, naturally a peninsula, was made an island by the Venetians

when they excavated a wet ditch for the fortifications which they constructed

for the defence of the land-front. There are still some remains of

the Hellenic fortifications of Nauplia to be seen on the brow of the table-summit,

which forms the south-western portion of the peninsula; towards its eastern

end the modern ramparts are in part composed of the ancient walls, which

are constructed very much like those of the citadel of Argos, and appear

to be of equal antiquity. There is a large piece of Hellenic wall,

also, towards the north-western end of the same height, and another smaller,

not far from the middle. But the most curious relic of antiquity

at Nauplia, perhaps, is the name Palamidhi, attached to the steep and lofty

mountain which rises from it to the south-east; for Palamedes having been

a native hero, the reputed son of Nauplius, who was son of Neptune and

Amymone, the name is so connected with the ancient local history of the

place, whether true or fabulous, that we cannot but infer that Palamedium

has been applied to this hill from a very early period, although no ancient

author has had occasion to notice it.

Before the year 1790, the Pasha of

the Morea resided at Anapli, which brought the agas to Anapli and the Greek

primates to Argos, and made the former town the Turkish, and the latter

the capital of the Peninsula; many Greeks were attracted also to Argos,

as I have already said, by the privileges which the place then enjoyed.

Much of the commerce of the Morea then centered at Anapli, and there were

several French mercantile houses. The moving of the seat of government

to Tripolitza in 1790, was followed by a plague, which lasted for three

years with little intermission; it prevailed in almost every part of the

Morea, but was particularly fatal in Anapli. Since that time the

town has not prospered; it is now only inhabited by the agas who possess

lands in the Argolis, by soldiers of the garrison amounting to about 200,

commaded by a Janissary aga, who resides in the fort of Palamidhi, and

by some Greek shopkeepers and artisans. The governor is a mirmiran,

or a pasha of two tails, whose authority does not extend beyond the walls

of the fortress; but there is also resident here a voivoda for the

vilayeti, a kadi, or judge, and a gumruktji, or collector of the Customs,

which last office is generally united with that of voivoda. The houses

are, many of them, in ruins, and falling into the streets; the French consulate,

a large house like the Okkals at Alexandria, is turned into a khan.

The port is filled up with mud and rubbish, and capable only of admitting

small polaccas, and to complete this picture of the effects of Turkish

domination, the air is rendered unhealthy on one side by the putrid mud

caused by the increasing shallowness of the bay, and on the other by the

uncultivated marshy lands along the head of the gulf. In the midst

of these miseries, however, the fortifications and store-houses of the

Venetians still exhibit a substantial grandeur never seen in a town entirely

Turkish, and testify the former importance of the place.

March 16. – It is pretended at Anapli

that the women are generally handsome, and those of Argos the contrary,

and it is ascribed to the water, which, at Argos, is drawn entirely from

wells, and at Anapli from a fine source in on of the rocky heights near

Tiryns, which is conveyed to the town by an aqueduct. This tale is

derived, perhaps, from the “muthos,” relating to the Nauplian spring

called Canathus, by washing in which Juno was said to have renewed

her virginity every year. I inquired in vain, however, for any natural

source of water in Anapli; and could only find an artificial fountain,

now dry in consequence of neglect, near the Latin church by the Custom-house:

but this source having been supplied from the aqueduct which I have mentioned,

could not have been the Canathus which Pausanias describes as a “pege,”

or natural spring.

Notwithstanding a buyurdi of the Pasha of the Morea, which I bring with

me, as well as a general firmahn of the Porte, I find some difficulty in

obtaining permission to see the fortress of Palamidhi. Before

the Pasha had read the order, and the kadi had summoned the ayans to take

it into consideration, all the forenoon had passed. But at length

an order is issued, and in the afternoon I ride up, by a circuitous route,

to the southern extremity of the castle, and entering by the gate on that

side, find the Janissary aga and his staff waiting for me at the gate;

he accompanies me round the fortress. It is of remarkable construction:

the interior part consists of three cavaliers, or high redoubts, entirely

surrounded by an outer and lower inclosure. There are many brass-guns

mounted on the ramparts, some of which carry stone-balls of a foot and

a half in diameter. The outer wall is low on the side towards the

sea, and the rock, though very precipitous on that side, is not inaccessible

to a surprise: the profile of these outer works is low also towards the

heights on the south, and they have no ditch; but there is an advanced

work adjoining the rocks at the southern extremity, the salient angle of

which is as high as that of the principal cavalier. Under the sea-face,

at the foot of the precipice, there is a road leading along the shore.

The rock on the sides towards the town and the plain is nearly as precipitous

as towards the sea, and more difficult to ascend: from the town there is

a covered passage of steps up to the fort, and on one side of it an open

flight, mounting zig-zag, the latter for common use, the former for security

in war. From the south-eastward only is the hill accessible.

There are nine cisterns of water in the fort about thirty feet long, six

wide, and six deep. There is a better provision of powder and artillery

here than is usual in Turkish fortresses. The body of the ramparts,

both of Palamidhi and of Indje Kalesi, as the Turks call the lower

fortress, are built of stone, with merlons of brick. The table-height

surrounded with cliffs, forming the summit of the peninsula of Anapli,

and around which are the remains of the Hellenic fortress, is unoccupied

with houses, and is fortified towards the sea only with a low wall, the

steepness of the cliffs furnishing a protection on that side of the peninsula.

These cliffs are covered with cactus, from whence, perhaps, has been derived

the name of Indje Kalesi, in allusion to the fig-like fruit of that plant.

The small island of St. Nicolas, three or four hundred yards off

the north-western point of the peninsula, is occupied by a castle; a little

within this the anchorage is deepest.

Notwithstanding a buyurdi of the Pasha of the Morea, which I bring with

me, as well as a general firmahn of the Porte, I find some difficulty in

obtaining permission to see the fortress of Palamidhi. Before

the Pasha had read the order, and the kadi had summoned the ayans to take

it into consideration, all the forenoon had passed. But at length

an order is issued, and in the afternoon I ride up, by a circuitous route,

to the southern extremity of the castle, and entering by the gate on that

side, find the Janissary aga and his staff waiting for me at the gate;

he accompanies me round the fortress. It is of remarkable construction:

the interior part consists of three cavaliers, or high redoubts, entirely

surrounded by an outer and lower inclosure. There are many brass-guns

mounted on the ramparts, some of which carry stone-balls of a foot and

a half in diameter. The outer wall is low on the side towards the

sea, and the rock, though very precipitous on that side, is not inaccessible

to a surprise: the profile of these outer works is low also towards the

heights on the south, and they have no ditch; but there is an advanced

work adjoining the rocks at the southern extremity, the salient angle of

which is as high as that of the principal cavalier. Under the sea-face,

at the foot of the precipice, there is a road leading along the shore.

The rock on the sides towards the town and the plain is nearly as precipitous

as towards the sea, and more difficult to ascend: from the town there is

a covered passage of steps up to the fort, and on one side of it an open

flight, mounting zig-zag, the latter for common use, the former for security

in war. From the south-eastward only is the hill accessible.

There are nine cisterns of water in the fort about thirty feet long, six

wide, and six deep. There is a better provision of powder and artillery

here than is usual in Turkish fortresses. The body of the ramparts,

both of Palamidhi and of Indje Kalesi, as the Turks call the lower

fortress, are built of stone, with merlons of brick. The table-height

surrounded with cliffs, forming the summit of the peninsula of Anapli,

and around which are the remains of the Hellenic fortress, is unoccupied

with houses, and is fortified towards the sea only with a low wall, the

steepness of the cliffs furnishing a protection on that side of the peninsula.

These cliffs are covered with cactus, from whence, perhaps, has been derived

the name of Indje Kalesi, in allusion to the fig-like fruit of that plant.

The small island of St. Nicolas, three or four hundred yards off

the north-western point of the peninsula, is occupied by a castle; a little

within this the anchorage is deepest.

Visitors to Classical Backpacking in Greece - Early Travelers, since 5.6.99