| |

|

|

|

| |

"Preface" in James

Laughlin, Byways: A memoir : Edited

with an introduction by Peter Glassgold ; Preface by Guy Davenport. (New

York: New Directions, 2005), pp. ix-xii. "First published clothbound and

as New Directions Paperbook 1000 in 2005" (verso t-p)

"These fragments of an autobiography were written at

Meadow House in Norfolk, Connecticut, between 3 a.m. and dawn, when the

cook arrived to serve James Laughlin his breakfast of blueberry muffins

and tea. He was not planning an orderly account of his eighty years,

only those memories that came to him in his insomnia and got him out of

bed and down to his typewriter, where he measured out phrases in the

neat short lines that William Carlos Williams had shown him how to

write.

* * *

He grew up rich and Presbyterian in a smoky steel town

from which Gertrude Stein's family had fled (to Oakland) and Mary

Cassatt's (to Philadelphia and Paris). George Washington had begun his

military career in Pittsburgh when it was a log fort besieged by French

and Indians. . . .

* * *

. . . Laughlin sought and found.

It was at tea with Edith Sitwell (coal tenders rumbling in the mines

beneath her country house) that he heard the name Dylan Thomas. Eliot

introduced Djuna Barnes; Pound, William Carlos Williams; Thomas Merton,

Nicanor Parra; Henry Miller, Hermann Hesse. Borges had to bounce off

French recognition. Laughlin also played a part in the resuscitation of

Henry James, E. M. Forster, and Faulkner. . . ."

* * *

.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

| "Foreword" in James Laughlin, The

Man

in the Wall. Poems by James Laughlin, (New York: New Directions, 1993), pp.

vii-ix. New Directions Paperbook 759. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

"Scripta Zukofskii Elogia" as

part of "Tributes to Louis Zukofsky (1904-1978)" by Hugh Kenner, Celia

Zukofsky, and David Gordon, eds., in James

Laughlin, ed., with Peter Glassgold and Frederick R. Martin.

New Directions in Prose and Poetry

39. [New York: New Directions, 1979],

pp. 159-164. Clothbound edition. Published also in 1979 as New

Directions Paperbook 484.

This essay was first published in Paideuma [Orono, ME: University of

Maine] 7:3 (Winter 1978) 394-399.

An elegy for poet Louis Zukofsky (1904-1978)

comprising 36 paragraphs, numbered 1 through 25, some of which with

sub-paragraphs numbered accordingly, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, and so on.

Excerpts:

1

Eighteen songs set to music by his wife [Celia] and fifty-three lines of

type in six blocks of prose; this is Zukofsky's Autobiography, not

his most eccentric work but certainly foremost as an eccentricity among the

world's autobiographies.

* * *

1.3

The city in which Zukofsky lived he pictured by translating Catullus, as

effective a recreation of the color, odor, and tone of its original as

Orff's Carmina Burana or Fellini's Satyricon.

1.4

The home in which Zukofsky lived is A. It contained two musicians, a

poet, many books, and a television set.

* * *

2.2

The most original meditation on Shakespeare since Coleridge. [Davenport here

is referring to Celia and Louis Zukofsky's Bottom: On Shakespeare.]

* * *

6

He taught at a polytechnic institute, saw the Brooklyn Bridge daily for

thirty years, was fascinated by the shapes of the letter [s] A

(tetrahedron. gable, strut) and Z (cantilever), and designed all his poetry

with an engineer's love of structure, of solidities, of harmony.

7

Le Style Apollinaire. LZ is a scrupulous punctuator, with correcter

parentheses, dashes, and semicolons than anyone else. Punctuation became

dense as the railroad tracks went down, corresponding to their points,

switches, signals, and semaphores. With the airplane, trackless and free, we

get Apollinaire with no punctuation at all, Eliot, Pound, Cummings.

* * *

13

He had the gift of the laconic. To Pound praising Mussolini in 1939, he

said, 'The voice, Ezra, the voice!' There must be hundreds of critical

postcards like ones I've had from him. Of my Archilochos, 'Something new!'

Of Flowers and Leaves, 'Yes, but where the passion?' Of my

Herakleitos, 'Jes' crazy!'

* * *

22

Two lives we lead: in the world and in our minds. Only a work of art can

show us how we do it. The sciences concerned with the one aren't on speaking

terms with those concerned with the other. Lenin once said that Socialism

would inspire in the working man a love of natural beauty. One of my

colleagues, a professor, once observed in front of my crackling, cozy

fireplace that it was such a day as one might want to sit in front of a

crackling, cozy fireplace if only people had such nice things anymore. I

thought I was losing my mind: he really did not notice that he was sitting

in front of a fire. His talk runs much to our need to expand our

consciousness. LZ in his poetry is constantly knitting the two worlds

together, fetching a detail from this one to match one in the other. And he

saw into other minds with a lively clarity.

* * *

Note: My copy of this

book has a book plate: Harvard College Lamont Library, stamped in red ink

'WITHDRAWN'. Harvard University Library property stamp dated 'Feb 05

1980'. I would like to think Lamont Library withdrew this book because it

was a duplicate copy.

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

[Prospectus essay] in James Laughlin, Stolen

&

Contaminated Poems. [Isla Vista, CA:] Turkey Press, MCMLXXXV [1985].

48-pp. photo-offset paper bound edition.

"Many Thanks to Robert Fitzgerald and W.

H. Ferry for their editorial assistance. Cover and design by Harry

Reese." (verso title page)

"This edition was photo-offset for the

author from the letterpress edition set in Dante type ad printed at

Turkey Press by Sandra Liddell Reese" (colophon p [49])

Davenport's essay:

"Is this deft and

effortless master of the epigram, who asks the woman at the tobacco

shop about Duke Federico d' Urbino's nose and has a radioactive

curiosity about the men and women who wrote and figure in poetry the

same James Laughlin who has shaped the literary sensibilities of three

generations of readers? Yes and no. Real poets are always somebody

else. Chaucer signed waybills for bales of wool, and Sidney rode under

flags behind the groan of drums. Cubism, Braque said, brought painting

within his capabilities. The reshaping of the classical epigram by

Pound, Williams, and Apollinaire brought that ancient art, with good

results and bad, within the capabilities of many, including James

Laughlin, sorting out from his other vast capabilities a whimsical

Mandarin poet whose fun (all mastery is joy) is to say, 'You didn't

think a poem like this could be written, did you?' Impossibility after

impossibility, he makes epigrams that nobody else could think of, much

less execute."

(back cover of this paperbound

edition)"

This copy annotated: "for Terry /

from Jas / (lotta E`z here)" (half-title page)

. |

| |

|

|

|

| |

"Wild Clover" in James Laughlin, ed.,

with Peter Glassgold and Griselda Ohannessian,

New

Directions in Prose and Poetry 50. (New York: New Directions, 1986), pp. 253-273.

"First published clothbound and as New Directions Paperbook #623 in 1986."

(verso-t-p following 'Acknowledgements')

Cover title: New

Directions 50: An International Anthology of Prose & Poetry; 50th

Anniversary Issue, 1936-1986

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

"Pound and Frobenius" in Lewis Leary, ed.,

Motive

and Method in 'The Cantos' of Ezra Pound, (1954; reprint New York: Columbia

University Press, 1961), pp. 33-59. "A Columbia Paperback."

Published as part of the series, Columbia University

English Institute Essays.

GD's essay was read first at the 1953 meeting of the English

Institute at Columbia University.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Ways of Being Human"

in

Coming

of Age: Photographs by Will McBride.

Introduction by Guy Davenport; Afterword by William Simon.

[New York:] Aperture, 1999. pp. 4- [7]

First edition.

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Balthus" in J. D. McClatchy, ed.,

Poets

on Painters: Essays on the Art of Painting by Twentieth-Century

Poets. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988, 1990) pp.

233-245. "First Paperback Printing 1990" (verso t-p)

GD's essay on Balthus is

preceded by editorial commentary:

"'I'm a

left-handed poet,' says Davenport, 'and a right-handed prose-writer.' He

[Davenport] continues to publish poems, and translations in verse, and

actually began as a poet -- his book-length Flowers and Leaves

appeared in 1966. 'Its failure to attract any notice whatsoever convinced

me that I should try prose.' His stories have since brought him to

prominence. They are not conventional stories but what he calls

'assemblages of history and necessary fiction.' Some of the history is art

history; some of the 'necessary fiction' is -- and neatly defines --

interpretation. Several of Davenport's stories, such as 'Tatlin!', 'Au

Tombeau de Charles Fourier,' and 'The Death of Picasso,' are in part

fanciful commentaries on painters, with asides like: 'Cezanne comes from

Virgil. Picasso takes up the Classical just when it was most anaemic,

academic, and bleached of its eroticism. . . . Traverse Picasso with

two vectors: the long tradition of the still life (eating, manners,

ritual, household) and the pastoral (herds, pasturage, horse, cavalier,

campsite).' Or this: 'Matisse began to include the edges especially of

women as they are seen more to the left than you would see if the right is

there and a little more to the right than you would see if the left is

here, a primitive and intelligent way of looking.' Among the subjects of

Davenport's brilliant, eclectic essays are Pavel Tchelitchew and Grant

Wood (whom he wants to see as the American Memling). In writing about

Balthus, Davenport is writing about the painter who has most attracted --

by his secret erotic grammar and allegorical literalism -- contemporary

poets, and he is thereby offering an oblique look at poetry too. Asked to

name the art criticism he himself likes best, he lists 'les frères

Goncourt on Hokusai and Hiroshige, Malraux's Goya, Adrian Stokes on

Duccio, Gertrude Stein on Raul Dufy (also on Picasso), Hugh Kenner on

Wyndham Lewis, Marilyn Aronberg Lavin on Piero della Francesca's The

Flagellation." (pp. 233-234).

|

|

|

|

[Cover Drawing] in Terje Maerli, ed.,

Samuel

Beckett: En Artikkelsamling, (Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1967).

Note on verso of title page: "Omslaget er tegnet av Guy

Davenport ... ."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

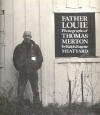

"Tom and Gene" in Barry Magid, ed.,

Father

Louie: Photographs of Thomas Merton by Ralph Eugene Meatyard, (New York:

Timken Publishers, 1991), pp. 23-36.

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

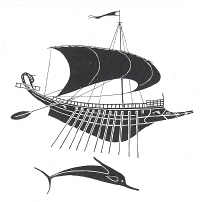

[Drawings] in Allen Mandelbaum, trans., The

Aeneid of Virgil: A Verse Translation

by Allen Mandelbaum. Drawings by Guy Davenport. (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1971)

"Jacket art by Leonard

Baskin" (dust jacket rear inner fold).

GD drawings (images reduced

in size):

Roman sailing ship with

oars ; a dolphin below. p. [xvi]

Goddess Juno ? p. 1

Charioteer driving a team

of four horses / the word ' R O M A' p.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Untitled Essay] in Matthew Marks, comp.

Artist’s Sketchbooks, (New

York: Matthew Marks Gallery, 1992), unpaged [3 pp. of a 54-page

monograph]

"This catalogue accompanies an exhibition held from

March 20 to May 4, 1991 at 1018 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10021."

(verso t-p)

"I am honored that Guy

Davenport agree to write for the catalogue. His willingness to undertake

this project, in spite of the rapidly approaching deadline, is much

appreciated." (Foreword by Marks)

Artists represented in the

Exhibit:

| Carl Andre |

Jackson

Pollock |

| Frank Auerbach |

Ad

Reinhardt |

| Louise Bourgeois |

Gerhard

Richter |

| Richmond

Burton |

Robert

Ryman |

| John

Chamberlain |

Julian

Schnabel |

|

Francesco Clemente |

Richard

Serra |

| Lucian

Freud |

David

Smith |

| Philip

Guston |

Myron

Stout |

| Gary

Hume |

Cy

Twombly |

| Jasper

Johns |

Andy

Warhol |

|

Ellsworth Kelly |

Lawrence

Weiner |

| Brice

Marden |

Terry

Winters

|

Excerpt from GD's essay follows:

IN LE CORBUSIER'S many sketchbooks, as in

Leonardo's, there is as much writing as drawing. These two complex minds

used sketchbooks to study, to meditate, to work out ideas, to record the

germ of image, to doodle. Sketchbooks are as revealing as diaries,

letters, records of conversations. Kafka's diaries are as well a

sketchbook for stories.

Corbusier the graphic artist and painter never

achieved in finished work the lively grace of his sketchbook pages. Some

of Leonardo's finest drawing is in the codices. Corbusier is his

architecture, built and unbuilt, his books, his theories. But to know

these without knowing the sketchbooks is to fall short of what Corbusier

left as a heritage. To some degree this is true of many artists. Van

Gogh's sketches in his letters, and his sketchbooks modify our knowledge

of his painting.

There are many things called sketchbooks.

There is the amateur's sketchbook, considered throughout the eighteenth

and nineteenth centuries to be a part of an educated person's skills. The

camera has displaced it. Gerard Manley Hopkins sketched, Ibsen sketched,

Hugo, Queen Victoria, everybody.

Then there is the field notebook -- Van Gogh

wading into mud and traffic, drawing; courtroom reporters; battlefield

artists; David making his hasty sketch of Marie Antoinette on her way to

the guillotine.

Next, the study book, worked on as a record

and as a generator of ideas. This kind of sketchbook goes back to Villard

de Honnecourt, mid-thirteenth century, to Pisanello, the Pepysian

manuscript at Cambridge, which is a pattern book like Hokusai's printed

sketchbooks, images for other artists to consult, study, and copy. This

kind of manual is apt nowadays to be photographic but nonetheless a true

sketchbook.

The peculiar claim of the sketchbook on our

attention is in its showing us inceptions and developments. Our century

has been curious to know how things come to be. There are more sketches

for Picasso's "Les Demoiselles d'Avignon" than for the oeuvres of all

other painters. Wittgenstein’s notebooks have elicited as much study as

his finished texts. In a sense, Wittgenstein has left us a progression of

sketches toward a philosophy rather than a philosophy. The poet Louis

Zukofsky carefully kept, and deposited at the Harry Ransome Research

Center in Austin, Texas, the intricately labored drafts of his long poem

“A”, with some idea, we can only suppose, that the gestation of his work

and its transformation from draft to draft, is not only significant but

complementary to the work. The subject of the poem is indeed work in all

of its senses.

Pound left his Cantos as a draft,

unfinished, as if the primacy of the sketch ought not to be superseded.

This feeling is in Cezanne's latter [sic, in recté later] canvases and

watercolors, and in practically all painters after him.

The grace of spontaneity, a new kind of

attention to process and becoming, innocence at the beginning of things --

reason after reason can be thought of to account for our delight in the

preliminary. We might note that once Darwin and the atomic theory shaped

our ideas, the encompassing idea of evolution changed the way we think

anything. The great question of our time is, “How did it come to be?”

It is easy to find Francis Ponge's notebooks

in which he composed his beautiful poem “The Meadow” as interesting, if

not more interesting, than the poem itself. Every work of art is at the

still center of two processes, that of its making, and that of its

comprehension. These can be symmetrical, a folding in and folding out.

It interested Ponge, when he wrote The Making of “The Meadow”, to

establish this symmetry himself, to run the film backwards, explaining how

it all came to be.

For most of the time, however, we have no such

record of beginnings and gestations. Thus sketchbooks, when they exist,

along with notebooks and journals, are rare and privileged perspectives, a

category all to themselves.

Paul Valery's notebooks, Gide's journals,

Roethke's “straw for the fire” (as he thought of his working notes),

Joyce's mysterious lists and schemata, Gaudier’s life-class studies --

these are a record of the work that went into a work,

Samuel Butler carefully revised his notebooks

as a polished work, much as many artists have used the sketch as a genre

in itself -- Rodin, for instance, in his quick studies of cathedrals and

models, We can add Jules Pascin, Braque, Klee, Avigdor Arikha. There is a

liveliness in Augustus John's T. E. Lawrence, Joyce, and Ronald Firbank

that no finished oil of John has. The subjects were all fugitive;

Lawrence and Firbank uncooperatively shy, Joyce impatient and annoyed.

Sketchbooks tend to be rich in sleeping subjects (Wyndham Lewis, of Pound,

his dog and his wife; Cocteau, of Radiguet).

A notation is by etymology a sign made the

moment something becomes known. The notarius wrote down the

witness's statement in a Roman Court. Early on, notatio took on

the meaning of “sharp observation, scrutiny.” Beside several sketches

Goya wrote, “I saw this.”

Visual annotation is close to writing.

Cocteau said of his drawings that they were writing untied and retied in

a different way. All drawing is an act of decisions, immediate revisions,

split-second deliberations; that is, intelligence at its most decisive,

creative potential. “Rest before labor,” said Blake. He might well have

said, “Play before work”, for the sketchbook is both playground and

testing place, the free exercise of pure intellect whether in doodling

(the draftsman's day dreaming) or in copying nature with precision. The

creative mind is prodigal, and its extravagance is at home in the

sketchbook, before its submission to the economy of the finished work of

art.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

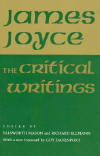

"Foreword to the Paperback Edition" in

Ellsworth Mason and Richard Ellmann, eds., The

Critical Writings of James Joyce,

(Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1989), pp. 3-6. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Introduction" to

Paul

Metcalf: Collected Works, Volume One 1956-1976. Minneapolis, MN: Coffee

House Press, 1996, pp. [i] - v.

Contents:

- Introduction

- Will West

- Genoa

- Patagoni

-

The Middle Passage

- Apalache

"Dust jacket

photograph [of Paul Metcalf] by Jonathan Williams" (verso t-p)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Note" in Thomas Meyer, ed., A

Garden Carried In A Pocket:

Guy Davenport [and] Jonathan Williams; Letters 1964--1968. Haverford, PA:

Green Shade [and] James S. Jaffe Rare Books, 2004, pp. 9-10. Book has 137 pp.

followed by 4 pp. of drawings. Includes photos of GD and JW.

Colophon:

This book was designed by

The Grenfell Press and printed by

Trifolio, Verona, Italy. The paper is Old Mill; the type is Minion.

Published in and edition of 526, of which 500 are bund in wrappers; of the

500, 100 are numbered and signed by the authors. 26 are bound in boards,

lettered A to Z, and signed by the authors.

Note: my copy (in wrappers)

is signed by Thomas Meyer and Jonathan Williams. It is a gift received from

Tom and Jonathan, during my visit to Skywinding Farm, Highlands, NC, on the

beautiful, warm and sunny Saturday of 15 January 2005.

|

|

|

|

| GD, by Ralph Eugene

Meatyard, late 1960s |

|

JW, by Arnold Gassan,

Aspen Institute, 1967 |

Editor's note:

"Here we have two men the

perfection of whose craft has been wrought through the practice of

letter-writing. And striking, the immense admiration and respect each

holds for the other's work. And too, their differences of temper and

element. Imagine Catullus writing to Heraclitus, or Fauré listening to

Scott Joplin, Sherlock Holmes and Joel Chandler Harris dunking havercakes

in chili. So far their exchange covers a good third of the last century,

and almost any imaginable subject. Should I say 'object'? Such is the

clarity their sentences set forth. A remarkable combination, The Pillow

Book of Sei Shonagon interleaved with a Sears, Roebuck Wishbook,

domestic detail and courtly gossip, an elegance of observation, complete

with Jeffersonian vitas. What we have here in particular is onset and

blossoming, one of the most distinguished exchanges imaginable unfolding."

(Thomas Meyer)

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Introduction" in Lenard D. Moore,

Forever Home,

with introduction by Guy Davenport and an Afterword by Fred Chappell, (Laurinburg, NC: St.

Andrews [College] Press, 1992), [unpaged, preceding "Table of

Contents"]. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Drawing] in Bradford Morrow,

Posthumes [broadside

poem]. New York, Grenfell Press, 1982.

I have two copies of this broadside, numbered #

___ and # ___ .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

[Drawing] in Rodney Needham,

Exemplars,

(Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1985) 17 [Plate 1].

Drawing [p. 17, 'Plate 1'] entitled "Archilochus" is of poet with a

round shield with a rooster emblem. In his acknowledgements, RN note: "He

drew it originally for his translation Carmina Archilochi (University of

California Press, 1964), where it was printed in reverse. Here it appears with

'Archilochus' in his true attitude: facing proper to right, and right-handed; also,

the swastika is displayed under its auspicious aspect."

Rodney Needham's essay, "Archilochus and the Intimation

of Archetypes" was written as a contribution to an unpublished Festschrift

in honor of GD's 50th birthday, November 23, 1977.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"A Note on the Text" in Denys Page, ed.,

Sappho

Fragmenta Nova [Prospectus] (Berkeley, CA: The Arif Press; Brookston, IN: The Twinrocker

Papermill, 1983), [pp. 4-5]. Unpaged [8 pp.]

Comment (verso half

title-page):

"The Arif Press of

Berkeley, California and Twinrocker Handmade Papers of Brookston, Indiana

are pleased to announce the publication of Fragmenta Nova;

being a group of newly identified fragments of the seventh-century BC Greek

poet Sappho. The issuance of these six poems supplements and brings up to

date her œuvre as represented by the Oxford University Press edition

of 1955.

The poems are in the

original language with the critical apparatus . . . printed in a second

color. Textual notes are also provided by the editor, the Oxford scholar,

Sir Denys Page. Readers desirous of reading all of Sappho that has survived

over two and a half millennia are directed to the admirable translations of

Guy Davenport: Archilochos, Sappho, Alkman: Three Lyric Poets of the Late

Bronze Age (Berkeley, 1980).

* * *

Excerpt from 'A Note on the

Text':

"Sappho lived and composed

songs in the city of Mytilene on the Aegean island of Lesbos around the last

decade of the seventh century before Christ. No whole poem of hers has

survived. It was the opinion of antiquity that she was one of the greatest

of lyric poets. Her music is lost forever, and all of her words except for a

dozen fragments coherent enough in their ruin on deteriorating parchment and

papyrus to give us a glimpse of the folk-song simplicity of her metric and

the startling brightness of her imagery. . . ." [p. 4]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Introduction" in Burton Raffel,

tr. Pure Pagan: Seven Centuries of Greek

Poems and Fragments. Selected and translated by Burton Raffel.

Introduction by Guy Davenport. New York: The Modern Library, 2004.

pp. [xiii] - xxii.

"This superb gathering of ancient Greek lyrics,

pungently translated by Burton Raffel, could not be more timely or more

timeless. The poems are by turns hilarious and heartrending, erotic and

elegiac, as fresh as the morning and shadowy as the dusk, yet always living,

inescapable, and wise. Guy Davenport contributes an arresting introduction

to this very welcome collection." (Robert Fagles, Translator of The Iliad

and The Odyssey -- dust jacket)

. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"A Moral Lecture for Food Snobs, Gourmets, Epicures,

Health Food Nuts, Gourmands, and People Who Pick On Their Children for Gulping Rock &

Roll Jelly Kings" in Charles J. Rubin [et al.],

Junk Food, (New

York: Dial Press/James Wade, 1980), p. 47.

GD's "favorite junk food is Zinger's; not crazy about

Tab." (Author's Credits, p. 8)

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Back to Parts of

Books (All) |