CHOCTAW CHIEFS AND LEADERS

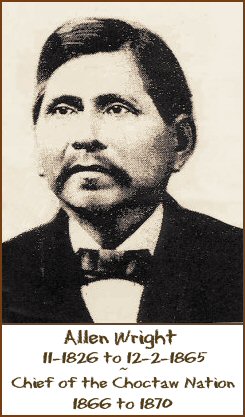

Allen Wright

Allen Wright was a Choctaw preacher, born in Mississippi about 1825; he emigrated with most of the tribe to Indian Territory in 1832, his parents dying soon afterward, leaving him and a sister. He had a strain of white blood, probably one-eighth or one-sixteenth. In his youth, he lived for some time with the family of the Rev. Cyrus Kingsbury, a Presbyterian missionary, and began his education in a missionary day-school near Doaksville. While here he was converted to the Christian faith, and soon after entered Spencer Academy in the Choctaw Nation. By reason of his studious habits he was sent by the Choctaw authorities to a school in Delaware, but afterward went to Union College, Schenectady, N. Y., where he was graduated in 1852. He then took a full course in Union Theological Seminary, New York City, being graduated in 1855, and in the following year was ordained by the Indian Presbytery. Returning to his people in Indian Territory; he preached to them until his death in 1885.

His people appreciating his ability and uprightness, Mr. Wright was called to affairs of state, being elected successively a member of the Choctaw House of Representatives and the Senate, and afterward Treasurer. In 1866, after the Civil War, he was sent to Washington as a delegate to negotiate a new treaty with the United States, and during his absence was elected principal chief of the Choctaw Nation, an office which he held until 1870. The Rev. John Edwards characterized Wright as "a man of large intelligence, good mind, an excellent preacher, and a very faithful laborer for the good of his people. No other Choctaw that I ever met could give such a clear explanation of difficult points in the grammar of the Choctaw." About 1873 he translated the Chickasaw constitution, which was published by the Chickasaw Nation, and in 1880 he published a "Chahta Leksikon." Just before his death he completed the translation of the Psalms from Hebrew into Choctaw. Soon after his graduation Mr. Wright married Miss Harriet Newell Mitchell, of Dayton, Ohio, to whom were born several children, including Eliphalet Mott Wright, M. D., of Olney, Okla.; Rev. Frank Hall Wright, of Dallas, Texas; Mrs Mary Wallace and Mrs Anna W. Ludlow, of Wapanucka, Okla.; Allen Wright, jr., a lawyer of South McAlester, Okla.; Mrs Clara E. Richards, Miss Kathrine Wright, and James B. Wright, C. E., all of Wapanucka, Okla.

Allen Wright

A second account, taken from; The Choctaw Nation Official Site

Chief of the Choctaw Nation from 1866 to 1870

Allen Wright was born in Attla County, Mississippi in November 1826. Known as Kilihote in his native language he was orphaned at the age of 13. He went to live with Reverend Cyrus Kingsbury and attended Pine Ridge Mission School near Doaksville. After four years there he entered the major tribal school, Spencer Academy. Later he attended Delaware College, Union College in New York and Union Theological Seminary in New York City. After completion of his studies he was ordained by the Presbyterian Church. He was the principal instructor at Armstrong Academy during the 1855-1856 school term. He married Harriet Newell Mitchello of Ohio in 1857.

Allen Wright became a member of the Choctaw Council in 1856, was elected treasurer of the Choctaw Nation in 1859, and under a new constitution he became a member of the Choctaw Council in 1861. During the Civil War the Choctaws joined forces with the Confederate Army. Because of their allegiance with the South they renounced all of its previous treaties with the United States. At the close of the war the tribe was in poverty and it was Allen Wright�s job as Principal Chief, to negotiate a new treaty with the United States and try to reorganize a badly split tribe.

He was elected Chief of the Choctaw Nation in 1866 and served until 1870. Some of his accomplishments included translating the laws of the Chickasaw Nation from English into their native language, Compiling a Choctaw dictionary for use in tribal schools, translating the book of Psalms from Hebrew into Choctaw, was editor of the Indian Chapion, and was a charter member of the first Masonic Lodge in Oklahoma. Chief Wright passed away December 2, 1885 and was buried at Boggy Depot in Atoka County.

Mushulatubee

He was a Choctaw chief, born in the last half of the 18th century. He was present at Washington D.C. in Dec. 1824, as one of the Choctaw delegation, where he met and became accuainted with Lafayette on his last visit to the United States. He led his warriors against the Creeks in connection with Jackson in 1812. He signed as leading chief the treaty of Choctaw Trading House, Miss., Oct 24, 1816; of Treaty Ground, Miss., Oct. 18, 1820; and the Dancing Rabbit Creek, Miss., Sept. 27, 1830. He died of smallpox at the agency in Arkansas, Sept 30, 1838. His name was later applied to a district in Indian Territory.

Peter Perkins Pitchlynn

He was a prominent Choctaw chief of mixed blood, born at the Indian town of Hushookwa, Noxubee County, Mississippi, Jan. 30, 1806; died in Washington, D. C., Jan. 17, 1881.

His father, John Pitchlynn, was a white man and an interpreter commissioned by Gen. Washington; his mother, Sophia Folsom, a Choctaw woman. While still a boy, seeing a partially educated member of his tribe write a letter, he resolved that he too would become educated, and although the nearest school was in Tennessee, 200 m. from his father's cabin, he managed to attend it for a season. Returning home at the close of the first quarter, he found his people negotiating a treaty with the general Government. As he considered the terms of this treaty a fraud upon his tribe, he refused to shake hands with Gen. Jackson, who had the matter in charge in behalf of the Washington authorities. Subsequently he entered an academy at Columbia, Tenn., and finally was graduated at the University of Nashville. Although he never changed his opinion regarding the treaty, he became a strong friend of Jackson, who was a trustee of the latter institution. On returning to his home in Mississippi, Pitchlynn became a farmer, built a cabin, and married Miss Rhoda Folsom, a Choctaw, the ceremony being performed by a Christian minister.

By his example and influence polygamy was abandoned by his people. He was selected by the Choctaw council in 1824 to enforce the restriction of the sale of spirituous liquors according to the treaty of Doaks Stand, Miss., Oct. 18, 1820, and in one year the traffic had ceased. As a reward for his services he was made a captain and elected a member of the National Council, when the United States Government determined to remove the Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creeks w.. of the Mississippi. His first proposition in that body was to establish a school, and, that the students might become familiar with the manners and customs of white people, it was located near Georgetown, Ky., rather than within the limits of the Choctaw country. Here it flourished for many years, supported by the funds of the nation. Pitchlynn was appointed one of the delegation sent to Indian Territory in 1828 to select the lands for their future homes and to make peace with the Osage, his tact and courage making his mission entirely successful. He later emigrated to the new reservation with his people and built a cabin on Arkansas river Pitchlynn was an admirer of Henry Clay, whom he met for the first time in 1840. He was ascending the Ohio in a steamboat when Mr. Clay came on board at Maysville. The Indian went into the cabin and found two farmers earnestly engaged in talking about their crops. After listening to them with great delight for more than an hour, he turned to his traveling companion, to whom he said: "If that old farmer with an ugly face had only been educated for the law, he would have made one of the greatest men in this country." He soon learned that the "old farmer" was Henry Clay. Charles Dickens, who met Pitchlynn on a steamboat on the Ohio river in 1842, gives an account of the interview in his American Notes, and calls him a chief; but he was not elected principal chief until 1860. In this capacity he went to Washington to protect the interests of his tribesmen, especially to prosecute their claims against the Government. At the breaking out of the Civil War Pitchlynn returned to Indian Territory, and although anxious that his people should remain neutral, found it impossible to induce them to maintain this position; indeed three of his sons espoused the Confederate cause. He himself remained a Union man to the end of the war, notwithstanding the fact that the Confederates raided his plantation of 600 acres and captured all his cattle, while the emancipation proclamation freed his 100 slaves. He was a natural orator, as his address to the President at the White House in 1855, his speeches before the congressional committees in 1868, and one delivered before a delegation of Quakers at Washington in 1869, abundantly prove. In 1865 he returned to Washington, where he remained as the agent of his people until his death, devoting attention chiefly to pressing the Choctaw claim for lands sold to the United States in 1830. In addition to the treaty of 1820, above referred to, he signed the treaty of Dancing Rabbit, Miss., Sept. 27, 1830, and the treaty of Washington, June 20, 1855, he also witnessed, as principal chief, that of Washington, Apr. 28, 1866. Pitchlynn's first wife having died, he married, at Washington, Mrs. Caroline Lombardy, a daughter of Godfrey Eckloff, who with two sons and one daughter survive him, the children by the first marriage having died during their father's lifetime.

Pitchlynn became a member of the Lutheran Memorial Church at Washington, and was a regular attendant until his last illness. He was a prominent member of the Masonic order, and on his death the funeral services were conducted in its behalf by Gen. Albert Pike. A monument was erected over his grave in Congressional Cemetery by the Choctaw Nation. In 1842 Pitchlynn was described by Dickens as a handsome man, with black hair, aquiline nose, broad cheek-bones, sunburnt complexion, and bright, keen, dark, and piercing eyes. He was fairly well read, and in both speaking and writing used good English. He was held in high esteem both by the members of his tribe and by all his Washington acquaintances.

See also Lanman, Recollections of Curious Characters, 1881.

Choctaw Chief from 1864 - 1866

Peter P. Pitchlynn was born in Noxubee County, Mississippi, January 30, 1806. His parents were Colonel John Pitchlynn, a white man, and Sophia Folsom, a Choctaw. He began his education by attending a Tennessee boarding school located about 200 miles from his home in Mississippi. Later he attended an Academy in Columbia, Tennessee. To complete his education he became a graduate of the University of Nashville. After he obtained his degree he returned to his home in Mississippi and became a farmer.

His first act was to erect a comfortable log cabin so he could marry Rhonda Folsom, his first cousin. Reverend Cyrus Kings bury, a missionary, performed the ceremony. After his first wife�s death, Peter married a widow, Mrs. Caroline Lombardy. Pitchlynn was instrumental in closing all the shops selling liquor to the Indians in Mississippi.

As a Council member he proposed the establishment of a school for Choctaw Children to be located in Kentucky. Because of his efforts the Choctaw Academy became a reality. He was also the forerunner of the removal of the Indian tribes to Indian Territory. The Choctaws looked upon him as their philosopher and friend. He represented them in Washington for many years.

Peter P. Pitchlynn was elected Principal Chief of the Choctaws in 1864 and served until 1866. After his tenure he retired in Washington, D. C. and devoted his attention to pressing the Choctaw claims for lands sold to the United States in 1830. In addition to being a regular attendant of the Lutheran Church, he was also a prominent member of the Masonic Order.

He passed away January 17, 1881 in Washington, D. C. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery where an impressive marker was erected over his grave by a grateful Choctaw Nation.

Pushmataha

Pushmataha (Apushim-alhtaha, 'the sapling is ready, or finished, for him.' Halvert).

A noted Choctaw, of unknown ancestry, born on the east bank of Noxuba Creek in Noxubee County, Mississippi in 1764; died at Washington D.C., Dec 24, 1824. before he was 20 years of age he distinguished himself in an expedition against the Osage, west of the Mississippi. The boy disappeared early in a conflict that lasted all day, and on rejoining the Choctaw warriors was jeered at and accused of cowardice, whereon Pushmataha replied "Let those laugh who can show more scalps than I can," forthwith producing five scalps, which he threw upon the ground the result of a single-handed onslaught on the enemy's rear. This incident gained for him the name "Eagle" and won for hint a chieftaincy; later he became mingo of the Oklahannali or Six Towns district of the Choctaw, and exercised much influence in promoting friendly relations with the whites. Although generally victorious, Pushmataha's war party on one occasion was attacked by a number of Cherokee and defeated. He is said to have moved into the present Texas, then Spanish territory, where he lived several years, adding to his reputation for prowess, on one occasion going alone at night to a Tonaqua (Tawakoni?) village, killing seven men with his own hand, and setting fire to several houses. During the next two years he made three more expeditions against the same people, adding eight scalps to his trophies. When Tecumseh visited the Choctaw in 1811 to persuade them to join in an uprising against the Americans, Pushmataha strongly opposed the movement, and it was largely through his influence that the Shawnee chief's mission among this tribe failed. During the War of 1812 most of the Choctaw became friendly to the United States through the opposition of Pushmataha and John Pitchlynn to a neutral course, Pushmataha being alleged to have said, on the last day of a ten days' council: "The Creeks were once our friends. They have joined the English and we must now follow different trails. When our fathers took the hand of Washington, they told him the Choctaw would always be friends of his nation, and Pushmataha can not be false to their promises. I am now ready to fight against both the English and the Creeks." He was at the head of 500 warriors during the war, engaging in 24 fights and serving under Jackson's eye in the Pensacola campaign. In 1813, with about 150 Choctaw warriors, he joined Gen. Claiborne and distinguished himself in the attack and defeat of the Creeks under Weatherford at Kantchati, or Holy Ground, on Alabama River, Ala.

While aiding the United States troops he was so rigid in his discipline that he soon succeeded in converting his wild warriors into efficient soldiers, while for his energy in fighting the Creeks and Seminole he became popularly known to the whites as "The Indian General."

Pushmataha signed the treaties of Nov. 16, 1805; Oct. 24, 1816; and Oct. 18, 1820. In negotiating the last treaty, at Doak's Stand, "he displayed much diplomacy and showed a business capacity equal to that of Gen. Jackson, against whom he was pitted, in driving a sharp bargain." In 1824 he went to Washington to negotiate another treaty in behalf of his tribe. Following a brief visit to Lafayette, then at the capital, Pushmataha became ill and died within 24 hours. In accordance with his request he was buried with military honors, a procession of 2,000 persons, military and civilian, accompanied by President Jackson, following his remains to Congressional Cemetery. A shaft bearing the following inscriptions was erected over his grave: "Pushmataha a Choctaw chief lies here. This monument to his memory is erected by his brother chiefs who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the General Government of the United States." " Push-ma-taha was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent in an extraordinary degree, and on all occasions, and under all circumstances, the white man's friend." "He died in Washington, on the 24th of December, 1824, of the croup, in the 60th year of his age." General Jackson frequently expressed the opinion that Pushmataha was the greatest and the bravest Indian he had ever known, and John Randolph of Roanoke, in pronouncing a eulogy on him in the Senate, uttered the words regarding his wisdom, his eloquence, and his friendship for the whites that afterward were inscribed on his monument. There is good reason to believe, however, that much of Pushmataha's reputation for eloquence was due in no small part to his interpreters. He was deeply interested in the education of his people, and it is said devoted $2,000 of his annuity for fifteen years toward the support of the Choctaw school system. As mingo of the Oklahannali, Pushmataha was succeeded by Nittakechi, "Day-prolonger." Several portraits of Pushmataha are extant, including one in the Redwood Library at Newport, R. I., one in possession of Gov. McCurtin at Kinta, Okla. (which was formerly in the Choctaw capitol), and another in a Washington restaurant. The first portrait, painted by C. B. King at Washington in 1824, shortly before Pushmataha's death, was burned in the Smithsonian fire of 1865.

Another account:

Pushmataha was born in east Mississippi in 1765, but his dominion

embraced our southwestern counties. The name Pushmataha means "He has won all the honors of his race." Of all the Indians, of pure blood who have a place in American history, he blended more admirable traits in his character than any other. He was intelligent, affable, sagacious, brave, eloquent, witty, and comparatively temperate, and, like Logan, he was truly the friend of the white man.' When told of the massacre at Fort Mimes, he rode to Mobile, in company with Mr. George S. Gaines, and offered his services and those of his tribe to Gen. Flournoy. And when they were accepted, he led a body of his warriors with the expedition of Gen. Claiborne, in the attack on Econochaca. While on his way to Washington, the last time, he rode through Demopolis, and there asked Col. G. S. Gaines to furnish his nephew with a keg of gunpowder, in the event of his death, so that suitable honors might be paid to his memory as a chief and a warrior. He died in Washington a few weeks later. Gen. Jackson visited him in his illness, and he was buried in the congressional cemetery with military honors. The tablet on his monument bears this inscription:

Pushmataha, a Choctaw chief, lies here. This monument is erected by his brother chiefs, who were associated with him in a delegation from their nation, in the year 1824, to the general assembly of the United States. He died in Washington, Dec. 24, 1824, of the croup, in the 60th year of his age. Pushmataha was a warrior of great distinction. He was wise in council, eloquent in an extraordinary degree, and, on all occasions, and under all circumstances, the white-man's friend. Among his last words were the following: 'When I am gone let the big guns be fired over me.' He said that his death would be like the falling of a great tree in the forest when the winds were still.

"Use this drop-down window to navigate my site"

|

|