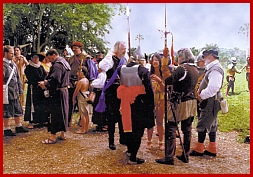

Below: Spanish Military Dress, Armada Campaign, 1588.

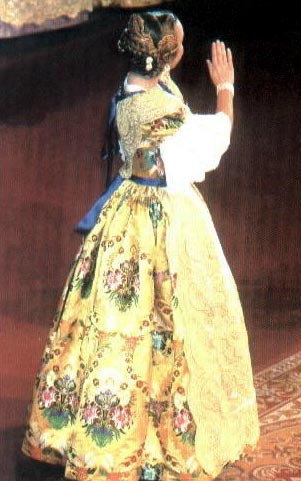

From Marc Simmons book Coronado's Land - Essays on Daily Life in Colonial New Mexico: [ppg 3-4] In 1598 Don Juan de O�ate and a wagon train of colonist marched north from the El Paso Valley to establish the first Spanish settlement in the Southwest. They expected to prosper and to create a shining center of Hispanic civilization on the upper Rio Grande. With that in mind the first settlers brought with them the fancy clothes they had been accustomed to wearing in central Mexico. The men had splendid velvet suits with high fluted collars and lace cuffs. They also wore sateen caps and expensive shoes from Cordova, Spain, richly carved and stitched. The women in the cavalcade were no less gaudily attired. Many had full silk dresses decorated with gold piping and lacy trim. Their hair was held by tortoise shell combs and covered with expensive fringed and embroidered shawls imported from Manila. They were shod in dainty slippers of bright colors. As it turned out, New Mexico proved to be so poor that no one was able to build palaces and mansions, for which such clothing might have been appropriate. Velvet and silk served well in the great cities farther south. But on the frontier they were totally impractical. Before long the colonists packed away their finery and took to dressing like the Indians. In other words, they began wearing clothes made of gamuza. That was simply buckskin, the softly tanned hide of deer and antelope, which abounded in the province. The Indians and Spaniards inhabiting the upper Rio Grande Valley in colonial days had a distinctive way of dressing their locks, one that conformed to ancient custom and perfectly suited them. The first requirement for both men and women was that the hair be left long. Males formed their heavy manes in two braids that hung down the back, sometimes as far as the waist. every man took special pride in his hair. The braids showed that he was a good and honorable citizen, and he would fight to preserve them. Short hair was a mark of dishonor. Only criminals, those recently released from jail, went about with their heads close-cropped. Such a man was called El Pel�n, or "Baldy". He was a social outcast and decent people refused to associate with him. Women wore a single braid, knotted and tied up on the back of their heads. It was a symbol of virtue. Ladies guilty of some moral indescretion might be seized by their fellow villagers and, with the snip of the scissors, shorn of their precious hair. No punishment was more severe, for the victim faced taunts and scorn from the community while the hair grew back. Until that happened, she was addressed only as La Pelona. On the New Mexico frontier of a century ago, Spanish women developed their own aids for facial improvement, using locally available mineral and vegetable products. They applied cosmetics so heavily that many of the first Anglos entering the territory were shocked. These men came from prim eastern society whre proper women did not rouge or powder their faces. The universal cosmetic of the Southwest was flour-paste, plastered in a thick coat from forehead to chin. It gave the appearance of a mask and one purpose was to protect the skin from the sun. A Yankee lawyer upon first observing ladies wearing a covering of flour wrote "They remain in this repulsive condition two or three weeks upon the eve of a grand ball or fiesta at which they desire to appear in all their freshness and beauty". Powdered chalk was sometimes substituted for flour. To both, women generally added some form of red coloring. German traveler Baldwin Mollhausen, visiting the Rio Grande Valley in the 1850s, spoke of the use of blood. "Faces of the feminie sex peeped curiously as we pased by the farms," he recorded. "But neither age, nor youth, beauty, nor ugliness could be discerned through the mask of chalk or the blook of cattle, with which they had seen fit to bedaub themselves." More commonly used as a rouge than cow's blood was a plant called alegr�a, which was red cockscomb. Maidens crushed the flowers, spit on them, then rubbed the crimson coloring on their cheeks. George Ruxton, a somewhat snobbish British youth, toured Mexico in 1846. Passing through Chichuahua and El Paso, he reached Socorro where he found that "the women besmear themselves with fresh coats of alegr�a when their faces become dirty; thus their countenances are covered with alternate strata of paint and dirt, caked and cracked in fissures." The heavy layers of powder and red paint served a funtion the critics never seemed to notice. They helped disguise pock marks, the terrible scars left by smallpox with which practically all New Mexicans in the old days were afflicted.If the Spanish ladies applied it a little too thickly to suit Anglo tastes, they had a reason. And, of course, some Hispanic women needed little makeup for their natural beauty to be obvious. Actually in some conservative New Mexico families, over-use of cosmetics was frowned upon. If a girl applied too heavy a coat of powder, one of her elders at the dinner table might say casually, "�A esta se le volco la olla!" meaning "This young lady seems to have let the pot boil over." The remarked referred to the ash cloud that rose and covered the cook's face when she allowed a boiling pot to spill into the fire. Thus shamed, the girl would rush from the table and scrub off the powder.

Left to Right: Light Pikeman, Officer, and Ensign.

The apparel shown in this illustration was typical of Spanish military dress both in Europe and in the New World during the last decades of the sixteenth century. Note the doublets and the peascod doublet-shaped body armor of the ensign.

Left to Right: Light Pikeman, Officer, and Ensign.

The apparel shown in this illustration was typical of Spanish military dress both in Europe and in the New World during the last decades of the sixteenth century. Note the doublets and the peascod doublet-shaped body armor of the ensign.Garments like these would have been worn at the time of the founding of St. Augustine, Florida in 1565 and the Spanish colonial occupation of Santa Elena on modern-day Parris Island, South Carolina during the 1566-1587 period.

Source: John Tincey and Richard Hook, The Armada Campaign 1588. (Oxford: Osprey Publishing, Osprey Military Elite Series No. 15, 1999, Plate K, p. 43.)

<

<