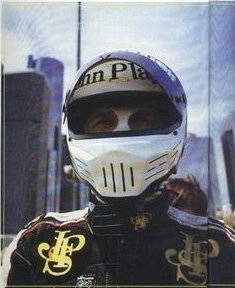

Tributes to Elio de Angelis

A

tribute to Elio by Mike Doodson, taken from the 1987 FOCA F1 Grand Prix

Yearbook

ELIO DE ANGELIS -

A Gentleman with ability and style

When

Elio De Angelis arrived in Formula 1 with Shadow, it was 1979: he was 20 years

old, with enough money from his father's civil engineering company to buy him

his place. By the end of that season, he had decided to move to Lotus, and

he was being sued for breach of contract. He later said he was happy that

Shadow wanted him to stay because of his ability, not his familys sponsorship.

When

Elio De Angelis arrived in Formula 1 with Shadow, it was 1979: he was 20 years

old, with enough money from his father's civil engineering company to buy him

his place. By the end of that season, he had decided to move to Lotus, and

he was being sued for breach of contract. He later said he was happy that

Shadow wanted him to stay because of his ability, not his familys sponsorship.

Driving racing cars

may seem like an enjoyable way for a rich young man to while away his

youth. Once, maybe that was true. Not in 1986, as Elio explained

'Everyone who comes into Formula One has to make a sacrifice, one way or

another,' he said. 'It's not that easy to come into F1: you can pay your

ticket in, but the ticket out is very easy. This is not an easy place to

sit. Tomorrow you can be sitting on the beach, without any apparent

reason.'

Finally, the

difficult sport at which this admirable Roman excelled also demanded the

ultimate sacrifice. It is possible that he died in vain. When his

Brabham ran off the Ricard track and overturned at 175mph during a test session

in May, there were no marshals at the Verrerie corner where the car landed and

caught fire. Witnesses have suggested that he died, not because of his

injuries, but because his brain had been starved of oxygen as he lay

trapped. His Father, Giulio, initiated a still unresolved legal action to

establish the truth.

It should not be

forgotten that he led the world championship points for several weeks in mid

1984 before the superior grip and reliability of the McLarens catapulted Lauda

and Prost ahead of his Lotus. Elio should certainly have won many more

Grands Prix than the two which stands to his credit. The first victory, at

the Osterreichring in 1982, was a memorable scrap which saw him cross the line a

tyre's width in front of Keke Rosberg. They were to become close friends,

perhaps because they could talk about things other than motor racing. Elio

loved his job, but he didn't take it home with him.

He was talented in

so many other ways, too. When he decided to race full-time in F1 he

learned to speak English in a matter of months. He could have been a

professional pianist ('but I didn't want to end up playing in an embassy

somewhere') and he would have made a fine diplomat. He knew the meaning of

old-fashioned values like loyalty and honour, qualities which he felt were not

forthcoming from Lotus in his sixth and last year with the British team.

Why, as his

long-term German girlfriend Ute Kittelberger, headed into her late twenties and

the end of her career as a model, he even talked of settling down and marrying

her. He had two brothers and a sister himself, so he was looking forward

to having a family of his own.

At the beginnings

of the Lotus contract he built up solid friendships with Colin Chapman and Mario

Andretti, both of them old enough to be his father. Later, after Chapman

died there were clashes of personality with those around him. He was harsh

about Nigel Mansells track manners, but actually asked to be forgiven soon

afterwards. He was never reconciled, though, to Ayrton Senna, whom he

accused of dangerous driving and machiavellian plotting.

Maybe Elio was

jealous of Senna's talent and fire, though he denied it: 'I've gone jumping over

the top of other cars and banged wheels with other people, I've done all those

things,' he insisted, 'but people tend to forget.'

The opportunity to

drive for Brabham in 1986 was one which gave him great pleasure. In spite

of the team's almost incessant setbacks with the revolutionary BT55

'skateboard', he admired designer Gordon Murray and liked the iconoclastic

Brabham mechanics. The respect was mutual. They weren't close to

making the new car a winner when Elio was killed, but he had put enough hard

work into the project by then to disprove all the theories about his alleged

lack of motivation. Murray was devastated but the accident, the first in

which a Brabham driver had been killed since he started designing cars for the

team in 1972.

In the aftermath of

the accident, there was a rush to condemn the Ricard circuit and a hasty volte-face

by FISA in its attitude towards turbo engines. It would be no tribute

to the memory of Elio De Angelis if he were to be remembered soley as the man

whose death catalysed the authorities into action, for he enhanced the image of

his chosen profession.

He was a driver who

had all the makings of a champion, in spite of, not because of, his

background. That is how we should honour his memory.

An

appreciation by Derek Allsopp

For

once, he didn't appear quite

so well-groomed, quite so sophisticated, and he had distinct problems

negociating the lingual chicanes. He spread himself across a corner of the

motorhome, his race suit half open and declared a little belatedly "tonight

I think I get a little drunk". Except that he didn't say "drunk".

For

once, he didn't appear quite

so well-groomed, quite so sophisticated, and he had distinct problems

negociating the lingual chicanes. He spread himself across a corner of the

motorhome, his race suit half open and declared a little belatedly "tonight

I think I get a little drunk". Except that he didn't say "drunk".

This was Elio de Angelis's way of enjoying victory, the second of his Formula

one career, at Imola. It was alas, to be his final victory and we were to enjoy

his driving and his company for just one more year. He died, after a terrible

crash in testing, at the Paul Ricard circuit in May 1986.

Perhaps if he had won more of his 108 races some of the uninhibited fun might

have evaporated from his hour of triumph. I like to think not. Elio had a

insatiable appetite for

the good things

in life and nothing exceeded

his delight in success. It can

be claimed - with a degree of justification - that he didn't chase that success

as forcefully as some. If the machinery met his requirements he would push

himself to the limit, if it didn't he would not attempt to defy logic or the

odds. Consider that and you have the retched irony of his death.

But there were always those who underestimated de Angelis, those who were

reluctant to acknowledge his quality. His arrival in F1 as another rich kid was

not calculated to smooth his path. Suspicion and envy find fertile ground in

this game.

I believe he was, at critical points in his career, a victim of circumstances

and misfortune. When he joined Lotus the great team was in decline anyway, but

his anxiety was compounded by the emergence of Nigel Mansell as a declared

challenger to his number one status and the death of Chapman.

The renaissance of Lotus gave him fresh optimism and eventually Mansell departed

to make way for Ayrton Senna. That was, however, the beginning of the end of his

association with the Norfolk camp. By the time of that 1985 San Marino Grand

Prix win, Senna had spelled out his own ambitions and the Latin cocktail proved

an impossible mix. Although de Angelis led Senna for much of the Championship he

was soon informed that the young Brazilian would be team leader for '86. "I

don't think it is fair, but what can I do?" Elio would ask. There was, of

course, only one answer and he left Lotus after six years with the team.

Again, he was to sign for a team with a glorious past, but an uncertain future.

Brabham were on the downward curve and a new car faced inevitable testing

problems. He had four races with Brabham, all without scoring, before his fatal

accident.

Yet, above the ill-luck and political in-fighting rose a rare man, a rare

driver, and the legacy of his is one we should cherish. Modern sport has a way

of draining the colour and substance from its exponents. De Angelis's resistance

to such a threat proved a marvellous exception. The driving reflected the man,

it had style, charm; it was easy, natural; it was unhurried, uncomplicated.

De Angelis was a roman, a fiercly proud Roman of wealthy stock. He had the looks

of a young Brando and the charisma, too. The debonair Elio didn't, however take

kindly to anyone ramming the silver spoon down his throat. "That makes me

angry" he would say.

When Elio was angry the glossy image cracked. He would remonstrate, gesticulate

in true Italian tradition. But mostly we saw another Elio; a warm wholesome,

intelligent, perceptive human, with a glint in his eye and a devastating smile.

He would engage you in frank, fascinating conversation on a range of fascinating

subjects then have you reeling in laughter at his jokes. Even in English, he was

the most captivating of raconteurs.

He was a multi-talented man. During the South African drivers' sit in of 1982,

Elio helped buoy morale with a splendid performance of classical music on the

piano. "Some day, when I finish racing, I will settle down, have a family

and play my piano".

He was a versatile sportsman. He loved skiing and tennis, and, as a player or

spectator, had a ferocious passion for football. But more than anything, he

craved speed, an obsession he inherited from his powerboat racing father Giulio.

Elio, the eldest of four children, raced with his father, and had a few

'character-building' mishaps along the way. He decided to seek fame on dry land.

He began racing karts at the age of 14 and was European champion at 18. He moved

on to cars and swiftly advanced through F3 and F2. He had his baptism of fire

with the Shadow team in 1979 and impressed sufficiently to earn his chance with

Lotus the following season, as partner to Mario Andretti.

His first Grand Prix success, at the Osterreichring in 1982, was one of the most

thrilling in the history of the World Championship. He managed to fend off Keke

Rosberg's Williams and take the decision by inches. Amid the chaos and confusion

and celebration that followed, he virtually ran down Chapman. The party spilled

into the night and into Italy, but victories were not to flow as readily as the

champagne.

Instead, de Angelis was to develop a reputation as a consistent finisher and

points scorer. He came third, behind the irresistible McLarens, in the 1984

championship and, when he achieved his second win the following spring, glimpsed

the prospect of the title itself. "Then we will have a REAL party", he

promised.

It was never to be. Elio died in a Marseille hospital on 15 May 1986 aged 28.

His car had cartwheeled over a barrier, landed upside down and burst into

flames. Approximately 8 minutes elapsed before he was released and then there

was a lengthy wait for a helicopter.

His death weighed heavily on the sport's conscience. There were sudden pledges

of improved safety standards for testing, of a reduction in power, of

modifications to the Ricard circuit.

I, for one though, will remember Elio for much more than the tragic

circumstances in which he died. You see, he really did give us so much to savour

and to celebrate, after all.

A

further tribute by Mike Doodson

Elio

de Angelis was looking forward to being with Brabham, a team that had made him offers

earlier in his career and which he felt would suit him better. However, he

insisted "As far as motivation is concerned, I have much more now than when

I started. Now I know exactly what I want - I'm not doing this just for the

pleasure of driving Formula 1". He was determined to add more victories to

the two he had won with Lotus, and if he had not sincerely believed that he

could not get that sort of success with Brabham, he would have given up racing

altogether.

Given the

radical 'skateboard' design of the Brabham BT55 and its lack of testing, those

goals seems rather further away than de Angelis had expected in the first four

races of the season. At Ricard last Wednesday, however, he and his new team were

edging a little closer to the success of which they were so confident, when his

car somersaulted off the road through the 170mph ess-bend after the pits. When

medical help finally arrived all

seemed hopeless. But he hung on for another 30 hours in a Marseille hospital

until he succumbed to serious head and chest injuries. He was 28.

Unlike many of

today's single minded drivers, there were genteel non racing facets to de

Angelis. Among other things, he was a classical pianist who also adored the

compositions of Stevie Wonder. Last year he told me "I think I'm going to

stop saying I'm a good musician, because I want to concentrate more on racing. I

had a chance to make a record, but I don't want it to detract from my

racing."

His racing career

started with karting in his early teens: he was Italian national champion in

1974 and second in the world championships of 1975. He won the Monaco F3 race in

1978 and for a brief period held a Ferrari contract - which he deliberately

dropped in order to join a British F2 team. When he arrived in F1, it was as a

renta-driver in 1979 with Ken Tyrrell, who changed his mind about his new

signing and promptly found himself on the wrong side of a high court judgement.

The de Angelis family money eased the youngster's way to Shadow, where an

amazing performance with a not very good car brought him fourth place and saved

Shadow's FOCA travel expenses for 1980. De Angelis quit, to join Lotus, and

promptly found himself in the same legal hot water where he'd left Tyrrell. The

years at Lotus saw a close, almost paternal relationship with Mario Andretti. He

had learned English in a matter of months and endeared himself by his loyalty to

his new team, which was already on a downturn. But he won a splendid first GP

victory in Austria in 1982, beating Keke Rosberg to the line by a tiny margin.

The two men were later to become close friends, largely on the basis that they

could spend time in each others company without necessarily talking shop. With

Lotus fixed up with Turbos in 1983 and eventually back on the bandwagon, de

Angelis was a consistent front runner. In 1984 he was the only man who could

match the McLarens, and for a short time in 1985 actually lead the World

Championship.

Already,

though, it was obvious that Ayrton Senna had taken over the number one position

in the team which de Angelis had worked so hard to achieve. His mechanic, Nigel

Stepney who had followed him from Shadow, said it was a carbon copy of the cold

shouldering which Nigel Mansell had suffered a year earlier. Paradoxically, it

was Senna who paid one of the sincerest possible tributes to de Angelis when the

news of his death was confirmed. "He was a very special sort of driver

because he did what he did out of love for the sport, not for any commercial

reason. He was well educated, a gentleman, someone who was good to know as a

person. I am sure he was not responsible for the accident at Ricard, because he

was someone who never went over the limit, who never pushed his luck."

Matters

of Moment - An

appreciation by Nigel Roebuck (Scanned From Motor Sport) NEW!

HOME

When

Elio De Angelis arrived in Formula 1 with Shadow, it was 1979: he was 20 years

old, with enough money from his father's civil engineering company to buy him

his place. By the end of that season, he had decided to move to Lotus, and

he was being sued for breach of contract. He later said he was happy that

Shadow wanted him to stay because of his ability, not his familys sponsorship.

When

Elio De Angelis arrived in Formula 1 with Shadow, it was 1979: he was 20 years

old, with enough money from his father's civil engineering company to buy him

his place. By the end of that season, he had decided to move to Lotus, and

he was being sued for breach of contract. He later said he was happy that

Shadow wanted him to stay because of his ability, not his familys sponsorship. For

once, he didn't appear quite

so well-groomed, quite so sophisticated, and he had distinct problems

negociating the lingual chicanes. He spread himself across a corner of the

motorhome, his race suit half open and declared a little belatedly "tonight

I think I get a little drunk". Except that he didn't say "drunk".

For

once, he didn't appear quite

so well-groomed, quite so sophisticated, and he had distinct problems

negociating the lingual chicanes. He spread himself across a corner of the

motorhome, his race suit half open and declared a little belatedly "tonight

I think I get a little drunk". Except that he didn't say "drunk".