|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Petty Officer Louis Robert Wood

|

|

|

|

Royal Fleet Reserve, H.M.S. Hogue |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lewis Robert Wood (he later used "Louis" as the preferred spelling for his first name) was born on 19 November 1881 at 5 Union

Place, off Cowick Street in Exeter. Within the family, he was known as "Lou", but he appears in the records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission under his middle name, Robert. |

|

|

|

Louis was the second of Frederick Louis Wood's thirteen children, and stayed behind in Britain when his parents emigrated to

Canada in 1905. In 1914, Louis was thirty-two years old, and a member of the Royal Fleet Reserve, which indicates that he was a Royal Navy veteran. As a Reservist, Louis was automatically called up when war was declared on 4 August.

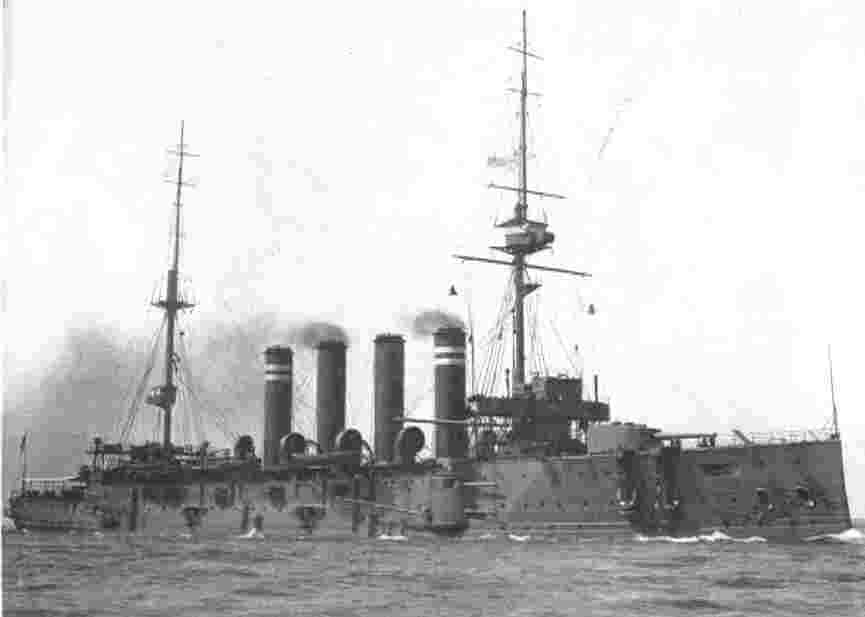

Due to

the plentiful number of naval reservists, the Royal Navy found itself with more men called up than could be accomodated on active ships, and adopted a policy of reactivating semi-obsolete vessels to be manned by the Reserve. They included three

cruisers of the "Cressy" class - HMS Cressy, HMS Hogue and HMS Aboukir - which were normally docked in semi-retirement on the Medway. These three slow, ageing vessels were painted and scraped, and assigned to the Royal Navy's 7th Cruiser Squadron. A

crew of more than 700 reservists was assigned to each -- including Louis, who became No. 161053, Petty Officer (Stoker) Louis Robert Wood, HMS Hogue. |

|

|

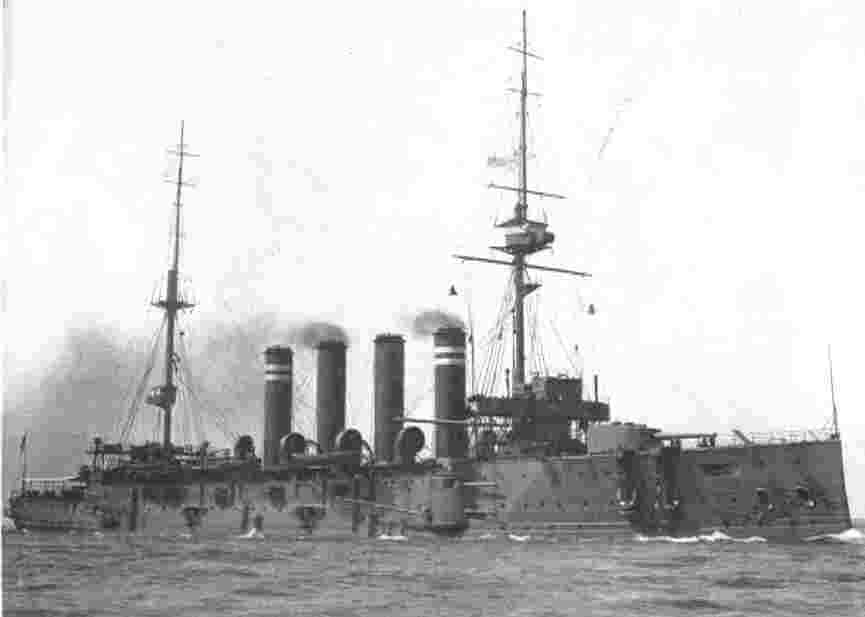

H.M.S. Hogue

|

|

|

|

(Photo courtesy Steve Johnson). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue were "local" ships, manned almost entirely by men who lived within walking distance of the Medway. These were primarily from

Chatham, Maidstone, Rochester and Gillingham, and most had limited naval experience and training. (Though the ships were commanded by seasoned regular Navy officers). |

|

|

|

|

In September 1914, the three cruisers were allocated to the Southern Force of the 7th Cruiser Squadron, and given

responsibility for patrolling the "Broad Fourteens" area of the North Sea (ie the northern part of the Dutch coast). The assignment was debated within the Admiralty -- some senior officers protested that a patrol of three aged cruisers would be a

sitting target for the modern vessels of the German North Sea Fleet, and the Cressy, Hogue and Aboukir were referred to informally as the "live bait" patrol. Nevertheless, the Admiralty confirmed the assignment on the grounds that no major German

vessels had been spotted in the Broad Fourteens, and it was believed that the very size of the old cruisers should deter the smaller German craft, ie torpedo boats and mine-layers, that were most likely to be encountered in that area. |

|

|

|

On 20 September 1914, the Cressy, Aboukir and Hogue set off on patrol in heavy weather which prevented their destroyer escorts

from accompanying them. Two days later, as they were patrolling twenty miles off the Hook of Holland on the early morning of September 22nd, the cruisers were spotted by the German submarine U-9.

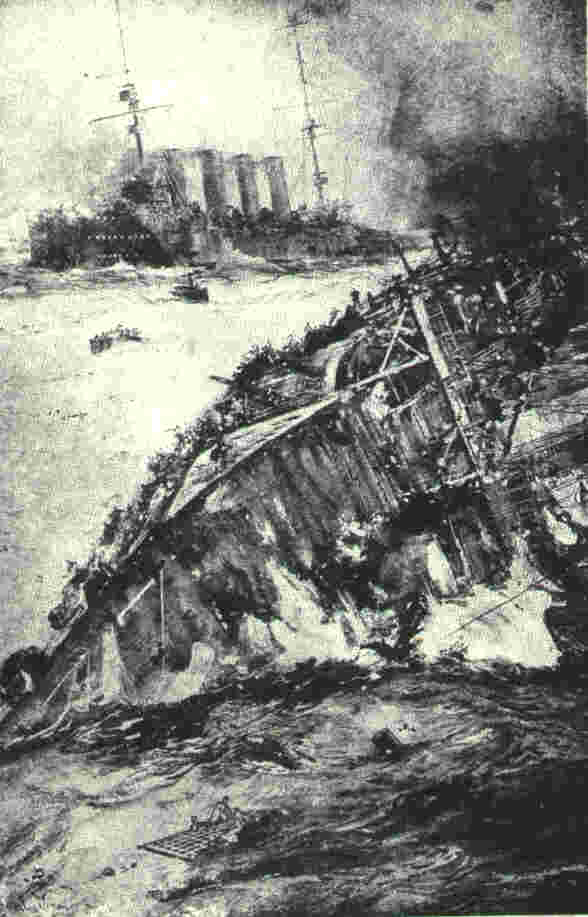

HMS Aboukir was attacked first. She was struck by

a single torpedo at 0630am, and sank within half an hour. Believing that the Aboukir had been sunk by a mine, rather than a torpedo, Hogue and Cressy approached to pick up survivors. At 0705am, while HMS Hogue was stationary and searching for

survivors, she was struck by two torpedoes on her starboard side, which left her engine room flooded. One crew member later recalled that there was "a terrific crash...the ship lifted up, quivering all over...a second or two later another and duller

crash and a great cloud of smoke, followed by a torrent of water....The noise for a second or two was deafening". |

|

The North Sea, with the Broad Fourteens Basin

indicated in red. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The crew of the Hogue managed to man her guns and fire at the U-9 and, once all her watertight doors were closed, it seemed

that the ship might stay afloat. But at 0710am, an explosion below decks sent her heeling violently to starboard. Unable to target their guns down into the water any longer, the Hogue's gunners ceased firing, and the order was given to abandon ship. By

0715am, HMS Hogue had sunk.

It was now apparent that the Aboukir and Hogue had been sunk by a submarine, rather than mines, and HMS Cressy began to zig-zag, in an attempt to avoid torpedo attack. But the Cressy too was torpedoed, and sank in a

single devastating explosion at 0730am. The entire attack upon the three cruisers had taken barely sixty minutes.

The closest Royal Navy vessels were over fifty miles distant from the attack, so the first rescue vessels on the scene were two

Dutch steamers and a British trawler, which arrived at about 0830am. These vessels took aboard the exhausted survivors whom they found clinging to wreckage from the three cruisers. Survivors picked up by British vessels were put ashore at Harwich, and

assembled at the Great Eastern Hotel, where hundreds of anxious relatives were waiting, in the hope of recognising their family member among the living. It soon became apparent to them that there were far too few survivors to account for the combined

ships' complements of almost 2,200, and that the loss of the three cruisers had been (in the words of the London Chronicle) "a disaster the meaning of which it would be foolish to minimise". |

|

|

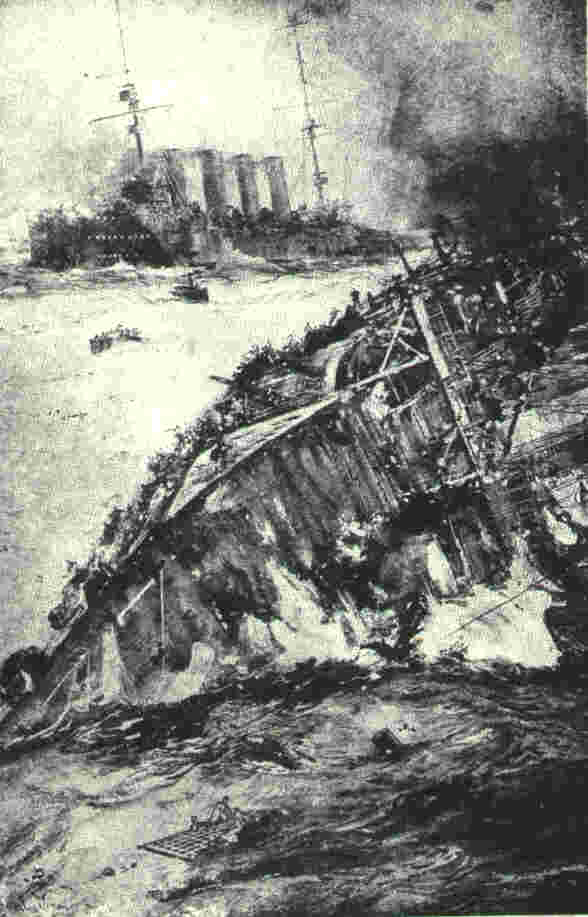

HMS Hogue closes to rescue survivors from the sinking Aboukir. (A contemporary print). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

In fact, the U-9's attack on the Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue would prove to be one of Britain's worst maritime disasters of the

Great War. Over eight hundred survivors from the three cruisers were recovered, but 1460 crewmen were lost, including Louis Wood. Petty Officer Louis Robert Wood was killed on 22 September 1914, when HMS Hogue was sunk off the Dutch North Sea coast.

His body was never recovered, and he is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial. |

|

|

|

The Chatham Naval Memorial |

|

|

(Details from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Chatham Naval Memorial stands in the Great Lines area of Chatham, closely overlooking the city centre streets where the

Wood sons grew up. It commemorates those Royal Navy crewmen whose home port was Chatham, and who were lost at sea during the two world wars. There are identical memorials at Plymouth and Portsmouth, honouring the sailors from those ports who died at

sea and have no known grave.

The Chatham Memorial was opened in 1924, and consisted at that time of a central memorial column (pictured above, left), inscribed: |

|

|

IN HONOUR OF THE NAVY,

AND TO THE ABIDING MEMORY OF THOSE RANKS AND RATINGS

WHO LAID DOWN THEIR LIVES IN DEFENCE OF

THE EMPIRE,

AND HAVE NO OTHER GRAVE THAN THE SEA. |

|

|

|

At the base of the column are attached a series of bronze panels, bearing the names of Royal Navy sailors who sailed out of

Chatham during the Great War, and never returned.

In 1952, the Memorial was extended to include the naval dead of the Second World War. The 1939-45 extension (pictured top right) comprises a semi-circular wall around the northern half of the

memorial column. It holds fifty bronze panels, bearing the names of 10,112 Royal Navy crewmen who were lost at sea. The central point of the wall is marked by a gateway bearing the inscription: |

|

|

ALL THESE WERE HONOURED IN THEIR GENERATIONS

AND WERE THE GLORY OF THEIR TIMES.

|

|

|

|

Louis Robert Wood is commorated by name on Panel 4 of the 1914-18 memorial column of the Chatham Naval Memorial (inscription

shown, lower right), along with more than 8,500 other Chatham sailors lost in the Great War. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

or return to Biographies Home Page |

|