|

|

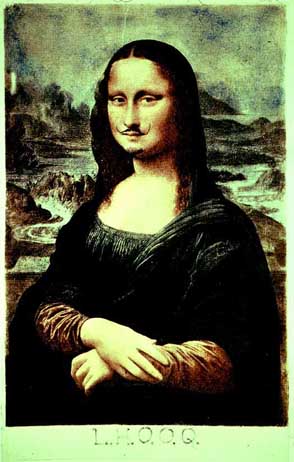

Taken from Dismantling The Da Vinci Code:

Brown�s analysis of da Vinci�s work is just as ridiculous. He presents the Mona Lisa as an androgynous self-portrait when it�s widely known to portray a real woman, Madonna Lisa, wife of Francesco di Bartolomeo del Giocondo. The name is certainly not�as Brown claims�a mocking anagram of two Egyptian fertility deities Amon and L�Isa (Italian for Isis). How did he miss the theory, propounded by the authors of The Templar Revelation, that the Shroud of Turin is a photographed self-portrait of da Vinci?

Taken from Cracks in the Da Vinci Code:

The Bizarre Interpretation of Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper in The Da Vinci Code

One of the most famous paintings in the world is Leonardo da Vinci�s The Last Supper. Leonardo painted it on the refectory wall of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, Italy, between 1495 and 1498. In this painting Leonardo attempts to capture the reactions of the twelve following Jesus� declaration: �Amen, amen I say to you, one of you shall betray me� (John 13:21).3 To establish compositional balance in the picture Leonardo grouped the twelve apostles into four groups of three, two on either side of Jesus. It is the threesome immediately at Jesus� right hand � to the left of him as we view the picture � that plays the most important role in The Da Vinci Code. There we see the figures of John, Judas, and Peter. The triangular structure of this grouping is derived from Peter�s leaning forward to ask John a question and John�s leaning back to hear it. In this Leonardo is following the cue of John 13:24: �Simon Peter therefore beckoned to him, and said to him: Who is it of whom he [Jesus] speaketh?� In the Gospel story, John then asks the question of Jesus and is told: �He it is to whom I shall reach bread dipped. And when he had dipped the bread, he gave it to Judas Iscariot� (John 13:26). And so, Judas is portrayed clutching the money bag in his right hand (see John 13:29), with his left hand hovering over a piece of bread on the table (apparently Leonardo alludes here as well to the words of Jesus in Matthew 26:23: �He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, he shall betray me� [cf. Mark 14:20]). The above interpretation is the standard one given by credible art historians since the time of Leonardo. The Da Vinci Code, however, offers another, very novel interpretation of this group of figures, one that it shares with, and probably derives from, an earlier book by conspiracy theorists Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince, entitled The Templar Revelation: Secret Guardians of the True Identity of Christ (1997). The Da Vinci Code explicitly praises The Templar Revelation on page 253.

On page 243 of The Da Vinci Code we encounter the following dialogue:

Sophie made her way closer to the painting, scanning the thirteen figures�Jesus Christ in the middle, six disciples on His left, and six on His right. �They�re all men,� she confirmed.

�Oh?� Teabing said. �How about the one seated in the place of honor, at the right hand of the Lord?�

Sophie examined the figure to Jesus� immediate right, focusing in. As she studied the person�s face and body, a wave of astonishment rose within her. The individual had flowing red hair, delicate folded hands, and the hint of a bosom. It was, without a doubt�female.

�That�s a woman!� Sophie exclaimed.

Teabing was laughing. �Surprise, surprise. Believe me, it�s no mistake. Leonardo was skilled at painting the difference between the sexes.�

...

Sophie moved closer to the image. The woman to Jesus� right was young and pious-looking, with a demure face, beautiful red hair, and hands folded quietly�.

�Who is she?� Sophie asked.

�That, my dear,� Teabing replied, �is Mary Magdalene.� (p. 243)

According to The Da Vinci Code, Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus, and their offspring included the Merovingian kings of France. Hence Mary Magdalene, and not the last-supper cup, was the Holy Grail, in that her womb served as the chalice from which the royal blood of Jesus flowed forth in a royal posterity. A mysterious society called the Priory of Sion (Leonardo was supposedly served as one-time Grand Master [p. 204]) was dedicated to protecting �the true history of Jesus,� which the Roman Catholic Church throughout its long history had energetically tried to suppress. This ancient antagonism between Rome and the Priory of Sion, The Da Vinci Code asserts, is also symbolically represented in The Last Supper:

[Teabing] �Jesus was the original feminist. He intended for the future of His Church to be in the Hands of Mary Magdalene.�

�And Peter had a problem with that,� Langdon said, pointing to The Last Supper. �That�s Peter there. You can see that Da Vinci was well aware of how Peter felt about Mary Magdalene.�

Again, Sophie was speechless. In the painting, Peter was leaning menacingly toward Mary Magdalene and slicing his blade-like hand across her neck. The same threatening gesture as in the Madonna on the Rocks!

�And here too,� Langdon said, pointing now to the crowd of disciples near Peter. �A bit ominous, no?�

Sophie squinted and saw a hand emerging from the crowd of disciples. �Is that hand wielding a dagger?�

�Yes. Stranger still, if you count the arms, you�ll see that this hand belongs to � no one at all. It�s disembodied. Anonymous.� (p. 248)

We will now respond to the Da Vinci Code�s assertions about The Last Supper in the reverse order:

(1) The dagger held in the hand of a disembodied arm.

The term dagger is ominous. But what we see in the picture is not a dagger. It is a knife. A dagger, as Webster�s Third New International Dictionary reminds us, is �a short weapon used for stabbing.� Nick Evangelista tells us in his The Encyclopedia of the Sword (1995) that the word dagger �derives from the Celtic word dag, meaning �to stab.��4 Given their purpose, daggers usually have thin pointed blades. The blade referred to in The Last Supper is too broad and not pointed enough to be justly described as a dagger. In addition, it also appears that only one of its edges is sharp, implying that its purpose was cutting not stabbing.

As to the arm, it is not disembodied. There are six disciples to Jesus� right in The Last Supper, and twelve arms and hands. The knife is in Peter�s right hand. This is evident from the painting itself and from the Study for the Right Arm of Peter in the Windsor Castle Royal Collection (no. 12546). The Templar Revelation had also referred to the knife as a dagger and had made the claim that it was being wielded in the picture by a disembodied arm and hand (p. 22).

(2) The menacing �blade-like hand,� just like the one in the Madonna on the Rocks.

The relaxed gesture of Peter�s right hand in The Last Supper (which points vaguely toward Jesus) relates to the request its owner was making of John. The gesture implies that Peter speaks to John behind his hand in a whisper. The only people, one would think, that would describe the hand as blade-like would be those who have not seen the painting since its most recent cleaning and restoration, completed in 1999. And indeed Dan Brown seems to be unfamiliar with this most recent restoration, since the only one he refers to in the context is one that, he appears to say, was concluded in 1954.5 This lapse on Brown�s part may derive from his reliance on The Templar Revelation, which, as we said, was published in 1997, two years before the completion of the most recent restoration. The Templar Revelation described Peter�s gesture as follows: �a hand cuts across her gracefully bent neck in what seems a threatening gesture� (p. 22).

Although the smudgy, unrestored version of Peter�s hand might have been described as blade-like, the hand on the present painting really cannot. Furthermore, even before the most recent restoration, the original character of Peter�s gesture could be clearly discerned from early copies of The Last Supper, such as the anonymous one at the Parish Church of Ponte Capriasca in Italy, and the one by G. A. Bultraffio, now at the London Royal Academy of Art (c. 1510). The most recent cleaning merely confirmed what was already known from early copies about Peter�s gesture.

As to the threatening gesture in the Madonna on the Rocks, The Da Vinci Code is again strikingly inaccurate in its interpretation (see pp. 13, 138-9). In its description of the picture as a whole, characters are misidentified and gestures inaccurately described. In this case, the hand of the angel Uriel is described as �making a cutting gesture as if slicing the invisible head gripped by Mary�s claw-like hand� (p. 139). A glance at the picture will reveal that Uriel is actually pointing placidly toward the child John the Baptist (which, by the way, The Da Vinci Code mistakes for the child Jesus). The gesture is in no way menacing. The Templar Revelation had offered the same bizarre reading of the Madonna on the Rocks, making the same mistakes about the gesture and about the identity of its characters (see esp. p. 30).

(3) Leonardo was �skilled at painting the difference between the sexes,� and the �delicate folded hands, and the hint of a bosom. It was, without a doubt�female.�

The reference to delicate folded hands as a proof that the figure traditionally identified as John was really Mary Magdalene is forced. In the Study for the Hands of John in the Windsor Castle Royal Collection (no. 12543), they do not appear distinctly feminine. They may be the hands of a woman, but then again they could as easily be those of a man. In The Last Supper itself, John�s hands are no less masculine than most of the other hands in the picture.

As for the hint of a bosom, this is entirely unjustified. Even if an overly fertile imagination might find such a �hint� in the folds of John�s cloak, nevertheless on the other side, where given the absence of the obscuring cloak we should be able to detect even clearer evidence of a bosom, we see instead that John�s chest is conspicuously bosomless. Are we then to suppose that Magdalene had only one breast? Here again Brown�s assertion may derive from reliance on The Templar Revelation, where we read of �the tiny, graceful hand, the pretty, elfin features, the distinctly female bosom and the gold necklace� (p. 20).7

Interestingly a more recent, post-1999-Last-Supper-restoration book by The Templar Revelations author Lynn Picknett now replaces the old distinctly female bosom claim, with the equally groundless assertion that there is �a dark smudge where �his� breasts should be.�8 Picknett apparently wants us now to believe that the female bosom was originally there, but that it was subsequently rubbed out.

In a posting from ABC News (Nov 3, 2003) we read:9

�Many art historians have dismissed the theory that the figure is a woman, saying it's just a tradition to paint John as beardless and long-haired. �It looks like a young male. I see no breasts,� art historian Jack Wasserman told ABCNEWS.�

Wasserman is a well-known Leonardo scholar.

Finally, John�s face is admittedly effeminate, but not more so than the faces of Jesus and Philip in the same picture. Many of the young, beardless men in Leonardo�s paintings and drawings are effeminate (see, for example, the startlingly effeminate St. John the Baptist in the Louvre).

This may relate to the artist�s homosexuality.

Read Brian Onken's brilliant review of this book that inspired the Da Vinci Code.

Pierre Plantard

"...the legitimacy of the Priory of Sion history rests on a cache of clippings and pseudonymous documents that even the authors of ''Holy Blood, Holy Grail'' suggest were planted in the Bibliotheque Nationale by a man named Pierre Plantard. As early as the 1970's, one of Plantard's confederates had admitted to helping him fabricate the materials, including genealogical tables portraying Plantard as a descendant of the Merovingians (and, presumably, of Jesus Christ) and a list of the Priory's past ''grand masters.'' This patently silly catalog of intellectual celebrities stars Botticelli, Isaac Newton, Jean Cocteau and, of course, Leonardo da Vinci -- and it's the same list Dan Brown trumpets, along with the alleged nine-century pedigree of the Priory, in the front matter for ''The Da Vinci Code,'' under the heading of ''Fact.'' Plantard, it eventually came out, was an inveterate rascal with a criminal record for fraud and affiliations with wartime anti-Semitic and right-wing groups. The actual Priory of Sion was a tiny, harmless group of like-minded friends formed in 1956.

Plantard's hoax was debunked by a series of (as yet untranslated) French books and a 1996 BBC documentary, but curiously enough, this set of shocking revelations hasn't proved as popular as the fantasia of ''Holy Blood, Holy Grail,'' or, for that matter, as ''The Da Vinci Code.'' The only thing more powerful than a worldwide conspiracy, it seems, is our desire to believe in one." [Laura Miller "The Da Vinci Con," The New York Times Review (Sunday, February 22, 2004), 23.]

Taken from Tektonics.org

|

..."The Bible did not arrive by fax from heaven... .The Bible is the product of man, my dear. Not of God. The Bible did not fall magically from the clouds. Man created it as a historical record of tumultuous times, and it has evolved through countless translations, additions, and revisions. History has never had a definitive version of the book." [Dan Brown, The DaVinci Code (Doubleday, 2003), 231.] |

Even in this vague summary, a host of problems emerges:

The implied view being addressed � that �the Bible arrived by fax from heaven� or �dropped out of the clouds� � is a tendentious straw man. The Bible was composed by men, yes, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. It is never claimed, however, that this inspiration involved the Spirit taking any kind of unnatural force over the Bible�s authors, much less that it fell from the clouds. Rather it is held that God chose specific instruments from men and that the Spirit guided them.

�Countless translations, etc.� is excessive hyperbole and vague generalization. Without a specific charge of what was translated, added, or revised, it is impossible to respond to this point specifically. Generally however, these considerations may be offered:

Translation issues for the Bible are not different than translation issues for any document, and cause no more difficulty. The statement implies that there is some great confusion over translation that is cause for concern. It is true that there are issues one may discuss in terms of translating the Bible from ancient Hebrew and Greek to any modern language, but this is a natural function of all translation processes, and in no way is this ever thought to detract from offering a �definitive,� reasonable account of what has been written. In fact, the transmission of the ancient texts, the voluminous quality of manuscript copies, the science of textual criticism, and the art of translation ensure that any reputable modern translation of the Bible is an accurate rendition of what was originally said. This subject has been covered so comprehensively and so well by so many scholars that Brown�s misrepresentation of the facts is inexcusable.

Brown�s imaginary arguments undermining the trustworthiness of the Biblical text are so unsophisticated and off the mark that one example will suffice to show his inadequacies. In Aramaic Sources of Mark's Gospel, Biblical scholar Maurice Casey examines the process of Mark's use of Aramaic sources in composing his Greek Gospel and offers a list of inevitable complications of translation and bilingualism and actual examples in practice. How a bilingual learns a language -- and how they keep up with it -- inevitably affects their translation ability. There is a vast difference between a person who grows up with both languages (and may therefore be less proficient in both of them) and a person who learned a second language, and did not use their first language for many years. A modern scholar who learns ancient Greek or Hebrew must encounter similar difficulties. As Casey puts it, "All bilinguals suffer from interference," and translators more so.[8] A few of examples offered by Casey bring this point home:

*Bilinguals "often use a linguistic item more frequently because it has a close parallel in their other language." Thus: "...Danish students are reported using the English definite article more often than monoglot speakers of English. This reflects 'the fact that Danish and English seem to have slightly different conceptions of what constitutes generic as opposed to specific reference.' " Or: "...there is a tendency for English loanwords among speakers of Austrian German to be feminine -- die Road, die Yard, etc. -- and this is probably due to the similarity in sound between the German die and the accented form of English 'the', whereas the German masculine der and neuter das sound different."

*When a source text is culture-specific, there is great need for changes to make the text intelligible. The example of how two German editions of Alice and Wonderland translated a particular passage differently serves well:

�Perhaps it doesn't understand English,� thought Alice, �I dare say it's a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.�

One edition substituted "English" so that the translation simply said that the mouse did not understand much, and to make the reference to William the Conqueror intelligible, added a phrase about William coming from England. A different translation made the language not understood by the mouse into German, and changed William the Conqueror into Napoleon. There were thus two different methods used to make the text intelligible to native readers.

*A German person on a bus asks a person next to an empty seat, "Ist dieser Platz frei?" It is literally in English, "Is this place free?" But an English person would say, "Is this seat taken?" Or, a polite request in Polish to a distinguished guest to take a seat is literally, in English, "Mrs Vanessa! Please! Sit! Sit!" The "short imperative" to "Sit!" sounds "like a command rather than a polite request" made to someone unruly rather than to a distinguished guest.

*Translating Dickens into German, there is a phrase in The Olde Curiosity Shop where a character speaks of it being "a fine week for ducks." English speakers naturally know this to mean it was a rainy week. A German translator however concluded that for us, "a fine week for ducks" meant it was a fine week to go hunting for them!

Such then are typical problems of translating from one language to another. The sort of exhaustive knowledge required to perform an exact translation is simply beyond the understanding of most people, and presents a practical impossibility. This does not mean we must press a panic button over not being able to provide �definitive� translations of every single word immediately, giving us the full range of meaning implied in every word, but nevertheless enough to be reasonably certain of what is being said. Even the examples above clearly transmit the main meaning of the passage, even if some nuance is lost to non-native speakers. Linguistic studies continue to be performed to this day giving us new insight into ancient languages. This is so not only for Biblical languages, but other ancient languages like Latin, and a professional historian, unlike our fictional Teabing, would never offer such a ridiculously generalized statement.

Additions and revisions are also of no more issue than those found in any other document. Again, without a specific �addition� or �revision� to address, we can only offer some general points. There are a number of �checkpoints� that give us a reasonable certainty of what the Bible originally said when written. The first set of checkpoints come through the process called textual criticism. Put simply, scholars collect and compare copies of the work in question, work out their relative ages, and by this means decide what the likeliest reading of the original document was. In terms of evidence, it is common to speak of the �embarrassing� wealth of evidence we have for the text of the New Testament, comprised of over 24,000 copies or pieces of manuscripts, some dating as early as the second and third century. In contrast, consider that the words of the Roman historian Tacitus, writing about 100 AD, are attested to by a mere handful of manuscripts (less than a dozen) which date to a far later time at the earliest (the eleventh century!). The Old Testament does not have quite as much or the same quality of manuscript evidence, but does still exceed significantly what is available from the likes of Tacitus and most other ancient works. On this basis, it is difficult to justify any claim that we do not possess a �definitive� idea of what the Bible actually said in its originals, or autographa, unless one wants to throw out all other ancient writings with it.

In terms of revisions, ancient writers did have justifiable reasons for performing certain types of revisions: As language changed or as certain facts become less known, it would become necessary to adjust the text in order for it to remain coherent to later readers. The Greek historian Herodotus, for example, used Greek measurement units to report weight, currency, and distance which would not have been used by the people of the places he reported upon. He does this even when translating inscriptions made by the people he is studying. Such revisions are very easy to discern and are not as problem for arriving at a �definitive� version of the biblical text. Moreover, they should not be mistaken for wholesale content-revisions, or changes in ideology, and they were certainly not �countless,� if we are to have any respect at all for the evidence provided by textual criticism.

|

�Jesus Christ was a historical figure of staggering influence, perhaps the most enigmatic and inspirational leader the world has ever seen�.Understandably, His life was recorded by thousands of followers across the land�.More than eighty gospels were considered for the New Testament, and yet only a relative few were chosen for inclusion � Matthew, Mark, Luke and John among them�The Bible, as we know it today, was collated by the pagan Roman emperor Constantine the Great.�[Brown, 231.]

|

Was Jesus a figure of �staggering influence� about whom �thousands of followers� wrote? The answers to these questions is, �No, not exactly,� and �No, not that the evidence would allow.�

Jesus became a figure of �staggering influence� only AFTER the Christian church became a prominent force. As far as the historians of the day were concerned, Jesus was just a "blip" on the screen. Jesus was not considered to be historically significant by historians of his time. He did not address the Roman Senate, or write extensive Greek philosophical treatises; He never traveled outside of the regions of Palestine, and was not a member of any known political party. It is only because Christians later made Jesus a "celebrity" that He became known. Historian E. P. Sanders, comparing Jesus to Alexander the Great, notes that the latter "so greatly altered the political situation in a large part of the world that the main outline of his public life is very well known indeed. Jesus did not change the social, political and economic circumstances in Palestine ..the superiority of evidence for Jesus is seen when we ask what he thought.� Jesus was also executed as a criminal, providing him with the ultimate �marginality�. He lived an offensive lifestyle and alienated many people. He associated with the despised and rejected: Tax collectors, prostitutes, and the band of fishermen He had as disciples. Finally, he was a poor, rural person in a land run by wealthy urbanites. The idea that Jesus had a �staggering influence� during his own life on earth is completely in error, which means that he could not have had �thousands of followers� to write authoritative biographies. In fact, three or four biographies would be the most we should expect � especially since 90 to 95 percent of all ancient persons were illiterate and unable to write such a work to begin with!

Were there eighty Gospels out of which four were chosen? If this is so, then we are justified in asking several questions:

1) What are the dates of the manuscripts of the �excluded� Gospels? If we are to consider any such work, we need to know how close it is to the time when Jesus lived. One way of determining this is to know what the earliest manuscript of it is. When we look at the evidence (sadly, evidence doesn�t seem to bother Brown in the least), we find that while there is near universal Christian knowledge and acceptance of the four canonical Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John) by the middle of the second century, none of the non-canonical Gospels were even close in date of composition, breadth of distribution, or proportion of acceptance. These were, for the most part, pseudo-gospels attributed to other Apostles but generally disqualified by most churches because they had no historical �chain of evidence� actually connecting them to real Apostles, and/or because they made claims that were contrary to what was already accepted in the canonical Gospels. This issue is also well known among Biblical scholars and information is easily obtainable in books written on a lay level such as Norman Geisler and William Nix�s A General Introduction to the Bible (Chicago: Moody Press, 1986) or online in sources such documented by the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia�s documents at http://www.reference-guides.com/isbe/B/BIBLE_THE_IV_CANONICITY/ .

2) Is there any evidence of this �excluded� Gospel being used at an earlier date? It is also useful to find citations of a work in contemporary writers, for if they quote a work, that is evidence that it existed at the time of their writing. Although there may have been as many as 50 pseudepigraphal gospels, most are known only by name from a few isolated statements by early church writers. The most significant ones are well known and the reasons they were never accepted by the majority of the church is well known and has never been kept secret by any hierarchy. Geisler and Nix provide lay readers with a good summary of this issue in their book referenced above (pages 297-317) saying, �the extra-canonical literature, taken as a whole, manifests a surprising poverty. The bulk of it is legendary, and bears the clear mark of a forgery. Only here and there amid a mass of worthless rubbish, do we come across a priceless jewel� (311). In fact, that �priceless jewel� in almost every instance is a mere repetition of what we find in one or more of the canonical Gospels.

3) Does the context cohere with what we would expect of the historical Jesus? In other words, if Jesus is said to open a �refrigerator� and take out a �burrito� and put it in a �microwave oven,� then we can be fairly sure that it does not accurately report the activities of a Jesus living in the first century. For example, in the Gospel of the Ebionites we find that John the Baptist didn�t eat honey and locusts, as the canonical Gospels record, but only honey. The Ebionites were vegetarians and didn�t let the truth get in the way of their dietary agenda. The Gospel of Peter laid the blame for the crucifixion solely at the feet of the Jews, exonerating the Romans � an anti-Semitic stance Brown should consider intolerable. The very �Gospels� Brown brings forth to undermine the consistent story of the canonical Gospels promote teachings completely contrary to the �secret� Christianity Brown says they represented!

It is this sort of data that scholars take into account when deciding whether a document is an authoritative source. In this chapter Brown does not name any of the other Gospels he has in mind, but he will name two of them in a later chapter, and we will address them in our discussion of those chapters. In closing, it is worth noting that Brown�s putative historian perpetrates two enormous blunders that would be an embarrassment to any scholar:

�Fortunately for historians�some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert.�

First, as I explained to the woman at the bookstore, the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947, not in the 1950s. (Note for those with problems: Three times I have had people write me claiming that Brown is right here because Dead Sea Scrolls continued to be discovered into the 1950s. But this is clearly not what Brown intends to report: If it were, he would have said that they were found beginning in 1947 and through the 1950s; as it is, his claim here remains a blunder. In addition, I have noted with satisfaction that two different experts in Burstein's guidebook [see below] peg Brown for exactly the same error.) Second, they did not contain any �gospels� or anything mentioning Jesus. They overwhelmingly predate the New Testament and are mostly copies of Old Testament books, and internal documents for the Qumran community. Brown also has his character allege that the Vatican �tried very hard to suppress the release of these Scrolls� because they contained damaging information. This is merely an obnoxious conspiracy theory found in popular writers, with no basis in fact. Again, the evidence concerning the Dead Sea Scrolls has been written about in so many books, journals, and articles, many on a lay level, that Brown can only make his erroneous statements with a complete disregard for the facts. There is nothing in the Dead Sea Scrolls that promotes either traditional or deviant Christianity. The community at Qumran responsible for the Scrolls was not Christian, but Jewish. While the Dead Sea Scrolls say nothing directly about Christianity, they do provide two important substantiations of traditional Christianity. First, the texts of the Old Testament preserved among the Dead Sea Scrolls provide us with verification that the Old Testament preserved by Jews and Christians throughout the centuries after Christ was an accurate rendition of what was known to Jews of Jesus� day. Second, the community at Qumran reflects a first century Judaism much more like that depicted by the New Testament writers than it does the Judaism that developed after the destruction of the Second Temple in A. D. 70. Those who speculated in times past that the Judaism presented in the New Testament was a later invention by Christian opposers to Judaism were refuted by what we have learned from the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Did Constantine decide the canon? How did the process work? Constantine was not the decider of the canon, and played in fact no role at all in its assembly; the church at large was the party responsible. The process of canonizing the New Testament was based on a model that had existed for centuries whereby various religions chose a collection of normative sacred books. It is likely that Paul himself began the process by collecting his own letters, or that one of his friends like Luke or Timothy did so. Far from being an arbitrary process, or one decided upon by Constantine much later, the formation of the canon was the result of carefully-weighed choices over time by concerned church officials and members. Later votes on the canon were merely the most definitive steps taken at the end of a long and careful, sometimes difficult, process. Biblical scholar Robert Grant, in The Formation of the New Testament, writes that the New Testament canon was:

...not the product of official assemblies or even of the studies of a few theologians. It reflects and expresses the ideal self-understanding of a whole religious movement which, in spite of temporal, geographical, and even ideological differences, could finally be united in accepting these 27 diverse documents as expressing the meaning of God's revelation in Jesus Christ and to his church.

To claim that Constantine was behind the canon, or was responsible for destroying Gospels he did not approve of, is a ludicrous distortion of history. In fact, Constantine convened the Council at Nicea, paid the travel expenses of those who attended, and provided his summer lake palace for the site, but he had no ecclesiastical authority at all. The information we have on the Council is fascinating and in no way supports the idea of a pagan Roman�s overthrow of �early Christianity� or any conspiracy. A good introduction to the facts about the Council is available in the Summer 1996 issue of Christian History magazine, �Heresy in the Early Church,� at http://www.christianitytoday.com/ch/51h/

|

�The vestiges of pagan religion in Christian symbology are undeniable. Egyptian sun disks became the halos of Catholic saints. Pictograms of Isis nursing her miraculously conceived son Horus became the blueprint for our modern images of the Virgin Mary nursing Baby Jesus. And virtually all the elements of the Catholic ritual � the miter, the altar, the doxology, and communion, the act of �God-eating� � were taken directly from earlier pagan mystery religions.� |

In his text Brown only names one particular mystery religion alleged to provide a source for Christian beliefs (see below), but in general, this can be said in reply:

The taking over of symbolism is true � but signifies ideological victory, not borrowing. Note to begin with that we are talking here not of apostolic Christianity of the first century, but of Christianity in the third and fourth centuries. What we see here is not so much �borrowing� but a sort of advertising campaign, or a type of artistic one-upmanship. The pagan deity Mithra was depicted slaying the bull while riding its back; the church did a lookalike scene with Samson killing a lion. Mithra sent arrows into a rock to bring forth water; the church changed that into Moses getting water from the rock at Horeb. Why was this done? It was done because this was an age when art usually was imitative. This is because the people of the New Testament world thought in terms of what could be "probabilities," or verification from general or prior experience. Imitation was a way of asserting your superiority: �Mithra is not the real hero. Samson is. Ignore Mithra.� �This mystery religion uses a miter as a sign of power. Well, we have the true power. We claim the miter for our own.� Note that the borrowing only involved art and ritual � it did not involve borrowing of ideology.

Now in terms of the only specific mystery religion Brown names, Mithraism:

The pre-Christian God Mithras � called the Son of God and the Light of the World � was born on December 25, died, was buried in a rock tomb, and then resurrected in three days.

Not surprisingly, scholars of Mithraism know nothing of any of this. Let�s look at the claims one at a time:

He was called the Son of God and the Light of the World. This is simply false. I have previously surveyed Mithraic studies literature and neither of these titles is noted by Mithraic scholars.

He was born on December 25. This may be true, but it is of no relevance, for the New Testament does not associate Dec. 25th with Jesus� birth at all. When the Christian Church chose December 25 as the birthday celebration for Jesus Christ, they did so in direct opposition to the pagan mid-winter festival of Saturnalia, not because they believed Jesus was born, like the pagan god(s), on that date.

He died,and was buried in a rock tomb, and then resurrected in three days. This is simply false. The Mithraic scholar Richard Gordon says plainly that there is �no death of Mithras � which means, there can be no burial of Mithras, and no resurrection of Mithras, either. Some amateur writers cite the church writer of the fourth century, Firmicus, who says that the Mithraists mourn the image of a dead Mithras; but this is far too late to have influenced Christianity (if anything, the influence was the other way around) and after reading the work of Firmicus, I found no such reference at all. More relevant perhaps is the late second-century church writer Tertullian's Prescription Against Heretics, chapter 40 which says, "if my memory still serves me, Mithra�sets his marks on the foreheads of his soldiers; celebrates also the oblation of bread, and introduces an image of a resurrection, and before a sword wreathes a crown�" The argument therefore relies on Tertullian's memory, and it isn't the initiates of Mithra, but Mithra, himself who introduces an �image� of a resurrection(?) � he is not �resurrected� himself.

Therefore, the comment of Brown�s character is a dismally erroneous assessment of what is reported by Mithraic scholarship.

|

�Christianity honored the Jewish Sabbath of Saturday, but Constantine shifted it to coincide with the pagan�s veneration day of the sun.�[Brown, 232-3] |

This is also simply false. All available evidence indicates that Christianity was honoring Sunday long before Constantine. Brown is perhaps confused because certain New Testament passages, for example, record Paul going to the synagogue on the Sabbath to preach to the Jews (if one wants to preach to the Jews and the Gentile God-fearers who attended with them, then it is logical to look for them where they are found - on the Sabbath, in the synagogue!). However, it is clear that Christian observations are held on the �first day of the week� (Acts 20:7, 1 Cor. 16:2; cf. Rev. 1:10), and there is also ample evidence of Sunday being observed well before Constantine:

1. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch (110 AD), wrote: "If, then, those who walk in the ancient practices attain to newness of hope, no longer observing the Sabbath, but fashioning their lives after the Lord's Day on which our life also arose through Him, that we may be found disciples of Jesus Christ, our only teacher.� Ignatius specifies the "Lord's Day" as the one on which "our life arises through Him" -- the resurrection day, which was a Sunday.

2. Justin Martyr (150 AD) describes Sunday as the day when Christians gather to read the scriptures and hold their assembly because it is both the initial day of creation and the day of the resurrection.

3. The Epistle of Barnabas (120-150) cites Isaiah 1:13 and indicates that the "eighth day" is a new beginning via the resurrection, and is the day to be kept

4. The Didache (70-75) instructs believers: "On the Lord's own day, gather yourselves together and break bread and give thanks."

5. Other later testimonies from Irenaeus, Cyprian, and Pliny the Younger, which pre-date Constantine significantly, testify that Christians worshipped on Sunday.

So once again, Brown�s �historian� receives a dismal grade in history.

|

�At [the Council of Nicea]�.many aspects of Christianity were debated and voted upon � the date of Easter, the role of the bishops, the administration of sacraments, and, of course, the divinity of Jesus�.until that moment in history, Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal prophet�a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless. A mortal.� [Brown, 233] |

This is a half-truth. The Council of Nicea did seriously consider alternating views of Jesus, not so much as �mortal� versus �God� but as �eternal� versus �created,� and they were debating because heretics had come out against the already-held view that Jesus was divine. The heretical view, held by the presbyter Arius, maintained that Jesus was not divine by nature, but was created in ages past by God. Jesus was thus not argued to be �mortal� or just a �great and powerful man� even by the heretical. (As an aside, Constantine, who Teabing blames so much on, was himself sympathetic to the Arians!)

Beyond this, the New Testament itself gives clear evidence of Jesus being viewed as divine:

� Through the New Testament, Jesus describes himself, and other New Testament writers describe him, in terms of the Wisdom of God, a pre-New Testament Jewish figure that was regarded as divine, and as an attribute of God personified.

� Jesus identified himself as the Son of Man, a phrase associated with a divine figure in Daniel 7.

� Paul in 1 Cor. 8:4-6 offers a revised version of the Jewish Shema which includes Jesus in the identity of Yahweh, the God of the Jews.

� A variety of New Testament passages affirm the absolute and full deity of Christ, such as John 1:1 (�the Word was God�), John 5:18 (�calling God His own Father, making himself equal with God�), John 20:28 (�[you are] my Lord and my God�), �Titus 2:13 (our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ,�), Romans 9:5 (�God over all, blessed forever�), and Colossians 2:9 (�within Him dwells all the fullness of being God in bodily form�), and others.

Chapter 55 of The DaVinci Code, then, is laden with error and represents the poorest scholarship one will find between two covers. To put these sorts of statements into the mouth of a historian is an insult to the profession.

|

��Jesus as a married man makes infinitely more sense than our standard biblical view of Jesus as a bachelor�Because Jesus was a Jew�the social decorum during that time virtually forbid a Jewish man to be unmarried. According to Jewish custom, celibacy was condemned, and the obligation for a Jewish father was to find a suitable wife for his son. If Jesus were not married, at least one of the Bible�s gospels would have mentioned it and offered some explanation for His unnatural state of bachelorhood.�[Brown, 245.]

|

All of this is in service of an explanation that Jesus was married to Mary Magdalene, and is taken not from any reputable source on Jewish customs, but from Baigent and Leigh�s material (see below). And is it correct? Once again Teabing would be pulled over by the History Police for this sort of bungle. First, he is committing the classic fallacy of argument from silence � you cannot affirm whatever you want simply because the text doesn�t deny it. Second, the following data from Glenn Miller�s Christian ThinkTank overturns his speculations altogether:

It would have been �normal� for [Jesus] to have been married, but not obligatory for that time (or any other time, for that matter).

1. The rabbinic literature--which is what people sometimes use to argue that celibacy was a capital offense(!)--notes and gives rules for exceptions to rules which were themselves non-binding:

"Celibacy was, in fact, not common, and was disapproved by the rabbis, who taught that a man should marry at eighteen, and that if he passed the age of twenty without taking a wife he transgressed a divine command and incurred God's displeasure. Postponement of marriage was permitted students of the Law that they might concentrate their attention on their studies, free from the cares of support a wife. Cases like that of Simeon be 'Azzai, who never married, were evidently infrequent. He had himself said that a man who did not marry was like one who shed blood, and diminished the likeness of God. One of his colleagues threw up to him that he was better at preaching that at practicing, to which he replied, What shall I do? My soul is enamored of the Law; the population of the world can be kept up by others...It is not to be imagined that pronouncements about the duty of marrying and the age at which people should marry actually regulated practice." [HI:JFCCE:2.119f]�

2. Judaism at the time of Jesus, of course, was a "many splintered thing", with the forerunners of the rabbinics being only one sect among many, one viewpoint (actually, multiple viewpoints!) on a spectrum of viewpoints. Accordingly, there were other groups at the time that either (a) required celibacy; or (b) allowed it.

The Essenes (and the somehow-related Qumran folks) were described by Josephus, Philo, and Pliny as being celibate, but the data is inconclusive as to whether they REQUIRED it or merely ENCOURAGED it. [OT:FAI:130ff]

Philo describes another Jewish sect of both men and women--the Therapeutae --who were celibate in their studies and pursuit of wisdom and the holy life (De Vita Contemplativa 68f).

3. But the dominant class of individuals who were �allowed� or �expected� to be celibate were prophetic figures, throughout Jewish history:

The prophet Jeremiah�

The wilderness prophet Banus:

"More well-known, though still exceptional, would have been the undoubted celibacy of wilderness prophets like Banus (Josephus Life 2.11) and John the Baptist." [DictNTB, s.v. "marriage"]

John the Baptist (and possibly his prototype Elijah]�

Even the 2nd century AD Hasidic miracle-worker, the Galilean rabbi Pinhas ben Yair taught that abstinence was essential to reception of prophetic wisdom and the Holy Spirit. [JJ:102]

4. Although the Rabbinic writers stressed the importance of marriage for procreation, it is noteworthy that this prophetic ideal of celibacy still showed up in the rabbinics:

"Judaism saw nothing wrong in portraying as celibate the great primordial prophet, seer, and lawgiver Moses (though only after the Lord had begun to speak to him). We see this interpretation already beginning to develop in Philo in the 1st century A.D. What is more surprising is that this idea is also reflected in various rabbinic passages. The gist of the tradition is an a fortiori argument. If the Israelites at Sinai had to abstain from women temporarily to prepare for God's brief, once-and- for-all address to them, how much more should Moses be permanently chaste, since God spoke regularly to him (see, e.g., b. Yabb. 87a). The same tradition, but from the viewpoint of the deprived wife, is related in the Sipre on Numbers 12.1 (99). Since the rabbis in general were unsympathetic--not to say hostile--to religious celibacy, the survival of this Moses tradition even in later rabbinic writings argues that the tradition was long-lived and widespread by the time of the rabbis� In view of this "marginal" tradition in early Judaism, it is hardly surprising that the Jewish scholar Geza Vermes has no difficulty in seeing Jesus as celibate and explaining his unusual state by his prophetic call and the reception of the Spirit." [MJ:1.340f]

So, although it would have been �normal� and expected for a young Jewish man to be married, we have examples of where celibacy was accepted, encouraged, or required. Therefore, Jesus would not have had to have been married�

Miller adds that it is a mistake to misuse Rabbinical literature (as Teabing is likely doing by Brown�s account) to assume that a rabbinic opinion was somehow a law. As the historian E.P. Sanders notes, according to Miller:

�There is also a more general point with regard to calling an opinion a law: once one starts quoting rabbinic statements as laws governing Palestine, one may draw absolutely any portrait of first-century Palestine that one wants. There are thousands and thousands of pages, filled with opinions." [JPB:463]

These �laws� may not be laws, but anything from �a simple description of common practice, which someone finally decided to write down� to a prohibition offered precisely because so many people were doing the opposite. It may be something intended only for the Pharisees, or may be an expression of an ideal that was never followed. As Miller notes, quoting Jewish scholar Ze'ev Safrai: "The public at large did not obey the rabbis. Among the Jews, only a minority followed the rabbis, obeyed their decisions and was influenced by their sermons and moral teachings�.The scholar or reader who wishes to do real history must take into account all sorts of possibilities when he or she faces a rabbinic passage; the response, 'everybody did it because the rabbis laid it down' is seldom the correct one."

Therefore, it is false to say that Jesus as a married man �makes infinitely more sense;� it is simply false to claim that the �social decorum� (or anything else) �virtually forbid a Jewish man to be unmarried;� it is false that �celibacy was condemned,� and the silence on the subject in the Gospels is not room for a positive proof whatsoever. (Let it finally be added, as many have noted, that Jesus does have a "bride" -- the church! This is how the body of believers is identified in Revelation, which clearly points to Jesus being single on earth.)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Home

|

|