Heraldry in the 21st century – can it survive?

by Mike Oettle

WHAT do Crusaders in shining armour have to do with Africa in the 21st century? Can a system of recognition devised in feudal Europe have any relevance in post-apartheid Africa?

The two cultural contexts are separated by a gulf that has been made even wider by the apartheid-era obsession with heraldic display that gave almost every white-controlled municipality (and many run by “Uncle Tom” black figures) its own coat of arms, every independent homeland state, every autonomous homeland state and even some tribal authorities.

And events in the 20th century have robbed heraldry of its former significance even in Europe, where the revolutions of 1917 and ’18 toppled three emperors (two of them also kings), three other kings and a slew of other princes and dukes.

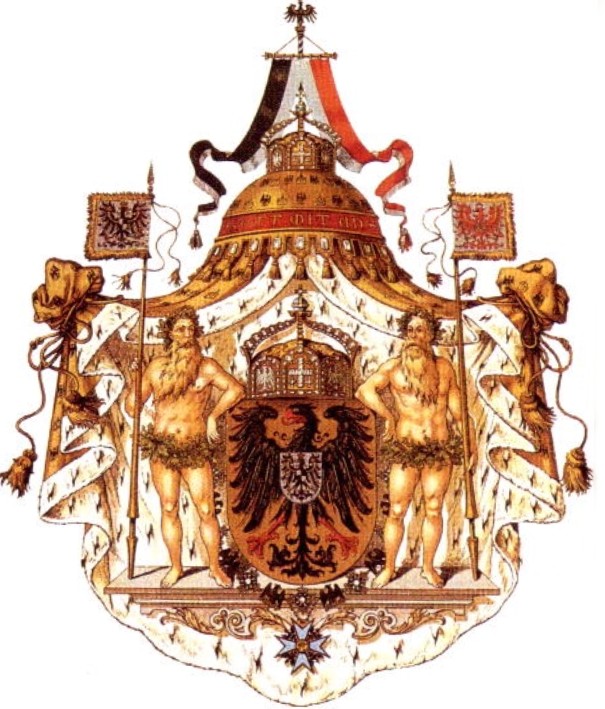

The heraldic display of these sovereign lords harked back on generations of consolidating lordships, of dynastic marriages and of proud conquest. It was also in a decadent state. Heraldry’s mediæval origins and simplicity had almost been forgotten as ever more elaborate displays of lordships crowded shields, or reduced the shield to a tiny proportion of the achievement, or complete display of the arms plus supporters and other ancillaries.

This can be seen in the arms of the German Emperor at left, where the shield charged with a black eagle on gold occupies considerably less than a third of the whole, and is in any case merely a prop for the display of the arms of the King of Prussia (a small silver shield on the eagle’s breast, showing another black eagle, this time charged with an even smaller shield on its breast). The title King of Prussia was what actually gave the emperor his wealth and power.

All that disappeared with the overthrow of these haughty rulers – but (except in Russia) their coats of arms survived, albeit without the crowns that formerly ensigned their shields, as the emblems of the new republics that took their place. Not only did the German Empire become a republic, but so did its constituent states of Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria, Saxony and Prussia become republics in their own right, each readopting the arms of its former ruler.

And the arms these republics adopted, while recalling the princes’ arms, were often a vast improvement, as in the arms (above at right) of the German Federal Republic.

Again with the exception of Russia, it was not until 1945 or even later that heraldry was tossed out altogether to the east of what came to be called the Iron Curtain. Socialist emblems, constructed with an appalling lack of originality according to a boringly repetitious pattern, were proudly displayed by the USSR, its constituent republics and many of the puppet regimes of the Warsaw Pact countries.

(It’s worth noting, however, a curious parallel with the arms of the Russian Tsars, shown below: while the Tsars displayed the arms of all their conquered provinces outside the shield of Russia, the Soviet Union represented all its diverse languages with red ribbons bearing translations of the slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” in each recognised language.)

Socialist thought permeated the universities of the West, too, and heraldry was condemned as something archaic, elitist, symbolic of exploitation and hopelessly out of touch with the modern world.

While Great Britain, handing over its colonial empire to the native inhabitants, gladly provided coat-armour and flags for the newly independent nations, other colonial powers did not. Spain and Portugal were in no position to grant such largesse, Portugal especially not since it retreated from socialist revolutions in its African possessions and was replaced by the neighbouring military in India and in Timor (where Indonesia seized power). Republican France saw itself as being above such holdovers of the ancien régime – although four of its colonies did adopt coats of arms that fully accord with the traditions of heraldry, and pseudo-heraldic devices were taken into use in several others. Lastly, Belgium was no longer welcome in the Congo, soon to become Zaïre.

America never really understood heraldry, making shields and other devices mere appendages (often in drab monotone) of the seals it regarded as the real symbols of its republican authority.[1]

In Europe, all that has changed following the fall in 1990-91 of most of the communist regimes. Post-communist governments of whatever stripe have been almost anxious to rediscover the heraldry of their feudal rulers, and wherever the Iron Curtain has been rolled back – as Churchill put it, it once stretched from Stettin (Szczecin) in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic – the pomp and gaiety of heraldry has reasserted itself as a counterweight to the greyness of socialist life that has not entirely disappeared from these countries.

(Even today it is said of travelling into eastern Germany that crossing the once heavily guarded border is like stepping into a black-and-white photograph.)

While heraldry was around in the late Middle Ages in the Balkan states and Poland, its spread further east came later, and is especially associated with Tsar Peter the Great. This explains the lack of mediæval simplicity in the arms of Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union – it is a tradition unknown in the land of the Tsars, and so is unavailable for revival in the enthusiasm for getting rid of socialist emblems.

In Africa, heraldry has a history of entering uninvited, from the first padrões erected by the navigators sent out by the Portuguese Order of Christ, to the republican devices of the Boer states of both the 19th and 20th centuries.

Yet it has a vitality that cannot be denied, a conciseness of expression that is unequalled and an attractiveness in its bold colourings that cannot but catch the eye.

Its chameleon-like ability to incorporate emblems, symbolism and colourings from other cultures gives it an adaptability that no other system of recognition can offer. Indeed, I believe that the great age of African heraldry is just dawning.