-

FACHARBEIT

aus dem Leistungskurs

Englisch

Thema:

Peace in Northern Ireland?

An analysis of the latest political developments in

Northern Ireland

(from the 1998 Good Friday Peace Accord to the present)

Verfasser: Andrea Staicu

Leistungskurs: Englisch

Kursleiter: Frau OStRin Zängle

Bearbeitungszeitraum: Kurshalbjahre 12/2 und 13/1

Abgabetermin: 1. Februar 2001

Erzielte Note:_____

Erzielte Punkte:_____

(einfache Wertung)

Abgabe am:_________

_______________________

(Unterschrift des Kursleiters)�

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction 3

- 2. Historical Background 4

- 2.1 The Plantation of Ulster 4

- 2.2 The Battle of the Boyne 5

- 2.3 The Great Famine 5

- 2.4 The Creation of Northern Ireland 6

- 2.5 The Beginning of the Troubles 7

- 3. The Good Friday Peace Accord 1998 8

- 4. The time after April 1998 10

- 4.1 Positive Developments after 1998 10

- 4.2 Negative Developments after 1998 12

- 4.3 Terrorist Activities after 1998 13

- 4.4 Further Attempts to Save the Situation 14

- 5. The Role of the US in the Peace Process 15

- 6. Statements to the Conflict 16

- 7. Personal Opinion 18

- 8. Sources used 20

- 9. Erklärung 22�

1. Introduction

1. Introduction

“Peace

process in ruins“,

“Hundreds of people injured at riots in

Northern

Ireland“,

“IRA makes zero process in giving up its

guns“ ...

People all over the world read such headlines nearly

every week in their newspapers. All these terrifying news concern one

problem which is a big burden for the innocent people who have to

live with it. The Northern Ireland Conflict

is a war between two different religious groups, the Catholic and the

Protestants, who live in the same country but support very different

attitudes towards political and religious issues. This conflict has

existed for more than thirty years and is characterized by violence

and a lack of tolerance towards people with other opinions. In the

last three decades the war killed more than 3,600 people and over

30,000 were injured, and there seems to be no end. Politicians in

Ireland and all over the world tried several times to find a solution

for the conflict, there were many negotiations between the different

parties but they never succeeded in finding a durable peace concept.

The last attempt to create peace in Northern Ireland took place in

April 1998 in Belfast. The two hostile groups signed the

“Belfast Agreement”, also known as the so called “Good

Friday Agreement” and a lot of hope was given to the Irish

people. Time passed, now we are at the beginning of the new

millennium and the question is: Have things changed in Northern

Ireland since then? Do the two different groups live in peace

together now or did the agreement fail?

On the following pages I will try to give you a short

overview of the conflict. Sometimes it is hard to understand why

people who live together in the same country and speak the same

language can not tolerate the different religious attitude of the

other group. I will try to explain what problems in the historical

background of Ireland led to the beginning of this conflict and how

the country developed in the past two years since the Good Friday

Agreement.�

2. Historical Background

It is

difficult to determine exactly what the roots of the conflict in

Northern Ireland are and when the trouble started. There are some key

dates which represent important milestones in Irish history. It all

started with the year 1170, when Henry II of England tried to

attach Ireland to his kingdom. He succeeded to conquer a small area

around Dublin, called “The Pale”.

This area adopted English administrative practices, the

English language and was looking to London for protection and

leadership. In the next decades some attempts were made in order to

extend English control over the rest of Ireland but they did not

succeed until the 16th century. In 1609,

military conquest had established English rule over most of

Ireland with the exception of Ulster. The province had succeeded in

creating an effective alliance against the foreign armies but after a

lot of fights the Irish were defeated and had to give up. Ulster was

brought under English control and British colonists confiscated and

distributed the land among themselves. By 1703, less than 5

per cent of the land of Ulster was still in the hand of the Irish.

[compare 4]

This area adopted English administrative practices, the

English language and was looking to London for protection and

leadership. In the next decades some attempts were made in order to

extend English control over the rest of Ireland but they did not

succeed until the 16th century. In 1609,

military conquest had established English rule over most of

Ireland with the exception of Ulster. The province had succeeded in

creating an effective alliance against the foreign armies but after a

lot of fights the Irish were defeated and had to give up. Ulster was

brought under English control and British colonists confiscated and

distributed the land among themselves. By 1703, less than 5

per cent of the land of Ulster was still in the hand of the Irish.

[compare 4]

2.1 The

Plantation of Ulster

The

Plantation of Ulster was unique among the Irish plantations in that

it set out to attract colonists of all classes from England, Scotland

and Wales by generous offers of land. Essentially it sought to

transplant a society to Ireland. The native Irish remained, but they

were excluded from the towns who were built by the Planters, and

banished to the mountains and bogs on the margins of the land they

had previously owned. The result of the Plantation of Ulster was the

introduction of a foreign community, which spoke a different

language, represented an alien culture and way of life, including a

new type of land tenure and management. In addition, most of the

newcomers were Protestant by religion, while the native Irish were

Catholic. So the broad outlines of the current conflict in Northern

Ireland had been sketched out within fifty years of the plantation:

the same territory was occupied by two hostile groups, one believing

the land had been usurped and the other believing that their tenure

was constantly under threat of rebellion. They often lived in

separate quarters and identified their differences as religious and

cultural as well as territorial. [compare 52]

2.2 The

Battle of the Boyne

The year

1690 is another key date in Irish history because of the

“Battle of the Boyne”. It was the decisive battle in the

struggle between former King James II of England and his successor

William III (also called William Orange) for the control of Ireland.

It was fought near the River Boyne, northwest of Dublin. James II was

a Roman Catholic and the Catholics ruled Ireland during his reign. In

1688, the English removed James from the throne and made

William III, a Protestant, king. The Irish prepared to rebel and

invited James to lead them. James borrowed troops from France. He

landed in Ireland in 1689. The English defeated him on the

banks of the Boyne on July 11th, 1690. The Battle

of the Boyne marked the beginning of Protestant control over

Catholics in Ireland. Its anniversary is celebrated by Protestants in

Northern Ireland and “Orange” became the distinctive colour

of the Protestants. [compare 23]

2.3 The

Great Famine

The

years 1845 to 1850 are probably the most tragic years

in Irish history because of the “Great Famine” which killed

more than one million people in less than five years.

“The

actual cause of (potato crop) failure was phytophthora infestans -

potato blight. The spores of the blight were carried by wind, rain

and insects and came to Ireland from Britain and the European

continent. A fungus affected the potato plants, producing black spots

and a white mould on the leaves, soon rotting the potato into a

pulp." [2; Potato Blight]

As harvests across Europe failed, the price of food rose

rapidly. Irish farmers found their food stores rotting in their

cellars, the crops they relied on to pay the rent to their British

and Protestant landlords destroyed. Peasants who ate the rotten

produce sickened and entire villages were consumed with cholera and

typhus.

On April 26th, 1849, Lord Clarendon wrote to Prime

Minister Russell: "...it is enough to drive one mad, day after

day, to read the appeals that are made and meet them all with a

negative... At Westport, and other places in Mayo, they have not a

shilling to make preparations for the cholera, but no assistance can

be given, and there is no credit for anything, as all our contractors

are ruined. Surely this is a state of things to justify you asking

the House of Commons for an advance, for I don't think there is

another legislature in Europe that would disregard such suffering as

now exists in the west of Ireland, or coldly persist in a policy of

extermination." [2; Cholera]

Landlords evicted hundreds of thousands of

peasants, who then crowded into disease-infested workhouses. [2;

Evictions] Other landlords paid for their tenants to emigrate,

sending hundreds of thousands of Irish to America and other

English-speaking countries, like Australia or Great Britain. "This

chaotic, panic-stricken and unregulated exodus was the largest single

population movement of the nineteenth century." [2; Emigration]

The combined forces of famine, disease and emigration depopulated the

island; Ireland's population dropped from 8 million before the famine

to 5 million years after. If Irish nationalism was dormant for the

first half of the nineteenth-century, the famine convinced Irish

citizens and Irish-Americans of the urgent need for political change.

2.4 The

Creation of Northern Ireland

The

following date is one of the most important for Ireland. The

partition of Ireland that took place in 1921 was a inevitable

outcome of the British attempts since the 12th century to

achieve dominance in Ireland. Throughout the centuries, insurrections

and rebellions by the native Irish against British rule had been

common. There has been pressure on the British government to grant

independence to the island and after World War I (1914-1918)

Britain agreed to limited independence. The pressure for “Home

Rule” in Ireland had been firmly resisted by Protestants in the

north who wanted to maintain the union with Britain. They feared

their absorption into a united, mainly Catholic Ireland, where they

believed their religious freedom would be restricted. Protestants

also feared the poorer economic state of the rest of the island,

compared to their own prosperous region. Most Catholics who lived in

the northern region and were the descendants of the indigenous people

who had been displaced by the settlers through the plantations,

wanted independence from Britain and an united Ireland.

The unionists threatened to use force if they were

coerced into a united Ireland and began to mobilize private armies

against such an eventuality. In an effort to compromise, the then

Prime Minister of Britain, Lloyd George, insisted that the island

should be partitioned into two sections, the six counties in the

north-east would remain part of the United Kingdom while the other 26

counties would gain independence. Each state would have its own

parliament. Irish nationalist leaders were divided over this

suggestion, but the offer was eventually accepted by those leaders

who were sent to conduct treaty negotiations with the British, as

they were anxious to avoid a return to an increasingly bloody

conflict in Ireland. It was also accepted by the unionists, although

reluctantly, as their first wish was for the whole of the island to

remain within the United Kingdom.

The decision to partition the island led to bitter civil conflicts

between those nationalists who accepted partition and those who

rejected it. Eventually, in 1923, those who accepted partition

achieved a bloody victory, and with the consent of Dublin and

Westminster the Irish Free State was formally created. The Irish

Constitution of 1937 adopted the title Eire (the Irish word

for Ireland) for the state. The state then declared itself a Republic

on Easter Monday 1949. The official title is therefore the

“Republic of Ireland”. [compare 84; 4]

2.5 The

Beginning of the Troubles

The last

important period in Irish history is the time after 1969 where

the troubles began. By the 1950s there were growing signs that

some Catholics were prepared to accept equality within Northern

Ireland rather than espouse the more traditional aim of securing a

united Ireland. In 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights

Association was formed to demand liberal reforms, including the

removal of discrimination in the allocation of jobs and houses,

permanent emergency legislation and electoral abuses. The campaign

was modelled on the civil rights campaign in the United States,

involving protests, marches, sit-ins and the use of the media to

public minority grievances. The local administration was unable to

handle the growing civil disorder, and in 1969 the British

government sent in troops to enforce order. While they were initially

welcomed by the Catholic population, they soon provided stimulus for

the revival of the republican movement. The newly formed Provisional

IRA began a campaign of violence against the army. By 1972 it

was clear that the local Northern Irish government, having introduced

internment in 1971 as a last attempt to impose control, was

unable to handle the situation. Invoking its powers under the

Government of Ireland Act, the Westminster parliament suspended the

Northern Ireland government and replaced it with direct rule from

Westminster. This situation continued into the 1990s. [compare

83]

On paper the civil rights campaign had been a remarkable

success. Several of its objectives had been conceded by the end of

1970. By that time, however, proceedings had developed their

own momentum. The IRA campaign developed strongly from 1972.

Instead of the riots between Catholics and Protestants which had

characterized 1969 and 1970, the conflict increasingly

took the form of violence between the Provisional IRA and the British

army, with occasional bloody interventions by loyalist

paramilitaries. The violence reached a peak in 1972, when 468

people died. Since then it has gradually declined to an annual

average of below 100. In the early 1990's, there were signs of

weariness over a conflict that clearly no one was winning. On August

31st, 1994, a dramatic breakthrough came when the

IRA announced a “complete cessation of military operations”

the cease-fire that set the stage for peace negotiations.

Protestant paramilitary groups of Northern Ireland also announced a

cease-fire on October 13th . The peace process had begun

but although the cease-fire was a crucial step, it only marked the

beginning of a long and hard process that involved appeasing the

demands of a number of different groups. Key players in the process

included the Protestant and the Catholic political parties, the IRA,

Sinn Fein, the British government, and the Republic of Ireland.

[compare 59; 32]

3. The

Good Friday Peace Accord 1998

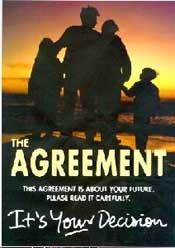

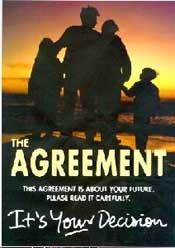

The Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday

Agreement) was reached on Friday, April 10th, 1998

in Belfast. It was the result of multi-party negotiations where all

people of the different parties in Northern Ireland tried to find a

way to co-operate in order to achieve a durable peace concept for

Northern Ireland after 30 years of war and terrorism. The most

important members who joined the negotiations were:

The Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday

Agreement) was reached on Friday, April 10th, 1998

in Belfast. It was the result of multi-party negotiations where all

people of the different parties in Northern Ireland tried to find a

way to co-operate in order to achieve a durable peace concept for

Northern Ireland after 30 years of war and terrorism. The most

important members who joined the negotiations were:

TONY BLAIR: Prime Minister of Great Britain,

SENATOR MITCHELL: Leader of Peace Talks,

DAVID TRIMBLE: Leader of the Protestant Unionist

Party,

GERRY ADAMS: Leader of the Sinn Fein, the

political arm of the IRA,

JOHN HUME: Leader of the SDLP (Social Democratic

and Labour Party) and

BERTIE AHERM: Prime Minister of the Irish

Republic.

The agreement sets out a plan for devolved

government in Northern Ireland where all sections of the community in

Northern Ireland would be prepared to participate in. It also

provided for the establishment of Human Rights and Equality

Commissions. The parties had to affirm the civil rights and the

religious liberties of everyone in the community.

- This meant the

right:

- - of free political

thought;

-

- to freedom and expression of religion;

-

- to pursue democratically national and political

aspirations;

-

- to seek constitutional change by peaceful and

legitimate means;

-

- to freely choose one’s place of residence;

-

- to equal opportunity in all social and economic

activity, regardless of class, creed,

-

disability, gender or ethnicity;

- to freedom from sectarian harassment; and

- of women to full and equal political participation.

[36]

The early release of terrorist prisoners from both sides

of the community, the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons and

far-reaching reforms of Criminal Justice and Policing in Northern

Ireland were also part of the Agreement. It also proposed an

inter-connected group of institutions that form three “Strands”

of relationships. Strand One deals with relationships within Northern

Ireland and created the Northern Ireland Assembly, its Executive and

the consultative Civic Forum. Members of the Assembly are voted in by

Proportional Representation and Ministers in the Northern Ireland

Executive are appointed according to party strengths in the Assembly.

All important decisions must have the support of both sides of the

community. For further information to the election of the Assembly

and its tasks read “The time after April 1998”.

Strand

Two deals with relationships between Northern Ireland and the

Republic of Ireland. A North-South Ministerial Council (NSMC) brings

together members of the Northern Ireland Executive and the Irish

Government. The NSMC oversees the work of six cross-border

Implementation Bodies. Strand Three deals with East-West

relationships within the British Isles. A British-Irish

Inter-Governmental Conference was established to promote bilateral

co-operation between the UK and Ireland. It replaces the Anglo-Irish

Inter-Governmental Council and Conference set up under the

Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985. A new British-Irish Council was

also created that incorporates members of all the devolved

administrations within the UK and representatives of the Isle of Man

and the Channel Islands as well as the British and Irish Governments.

Its goal will be the harmonious and mutually beneficial development

of the totality of relationships among the people of the islands.

A final

section covered validation, implementation and review. It was agreed

that referendums would be held in both parts of Ireland on May 22nd,

1998. If there were public endorsement North and South, the

two governments would take all necessary legislative and other steps

to bring all the new institutions into being, and to give effect to

constitutional changes. [compare 56; 36]

4. The

time after April 1998

The agreement seemed

to solve all problems of the country if it worked like all

participants of the negotiations hoped but everybody was realistic

and knew that the implementation of the agreement would be very

difficult. There were still a lot of issues between the different

sides and all agreements reached in the past did not succeed, mostly

because of the question of decommission.

The time after the referendum on May 22nd,

where the majority of people in the North and the South voted with

“yes“ on the agreement (in Northern Ireland 71.2% of the

voters and in the Republic of Ireland 94% voted “yes”)

[26] could have been a period during which the letter and the spirit

of the Good Friday Agreement was fully utilized, a period when Irish

nationalists, unionists and the British moved towards each other in

an effort to put behind them the enmity resulting from centuries of

conflict.

The time after the referendum on May 22nd,

where the majority of people in the North and the South voted with

“yes“ on the agreement (in Northern Ireland 71.2% of the

voters and in the Republic of Ireland 94% voted “yes”)

[26] could have been a period during which the letter and the spirit

of the Good Friday Agreement was fully utilized, a period when Irish

nationalists, unionists and the British moved towards each other in

an effort to put behind them the enmity resulting from centuries of

conflict.

It could

have been a time when former enemies gave space to each other to

learn new ways of thinking, of speaking, of trying to understand one

another. A time of certainty and decisive, forward looking leadership

to demonstrate that they had turned the corner - that a new chapter

had opened in Irish-British history - that compromise, tolerance and

the beginning of a process of reconciliation had replaced domination,

intolerance and division.

But what happened? Did the expectations come true? This

question can not be answered easily with yes or no because there were

positive developments which gave the people hope for peace but also

discouraging incidences which seemed to destroy the fragile peace

process.

4.1

Positive Developments after 1998

If you

look to the positive developments you can say: “Yes, the

expectations came true, we are on the right way!”

The

following occurrences belong to the positive ones:

Elections

took place to the new Northern Ireland Assembly on June 25th,

1998. The Ulster Unionists are the biggest assembly party with

28 seats, followed by the SDLP with 24, then the Democratic Unionists

with 20, and Sinn Fein has 18 seats. A variety of smaller parties

made up the remaining seats, for a total of 108. Looking at the

results of the election, it is a good sign, that all parties sit

together and try to find solutions for the problems.

Here

are the exact results: [26]

|

Party |

Seats |

|

Ulster

Unionist Party |

28 |

|

Social

Democratic and Labour Party |

24 |

|

Democratic

Unionist Party |

20 |

|

Sinn

Fein |

18 |

|

The

Alliance Party |

6 |

|

United

Kingdom Unionist Party |

5 |

|

Progressive

Unionist Party |

2 |

|

Northern

Ireland Women's Coalition |

2 |

|

Others |

3 |

The

first task of the new, 108-seat Northern Ireland Assembly was to

create a North-South Ministerial Council to work on cross-border

issues, including tourism and economic development. Although the

council draws members from Dublin, it is accountable to the Assembly.

A Council of the Isles, comprising delegates from Belfast, Dublin,

and London, as well as from soon-to-be-created assemblies in Scotland

and Wales, also are set up. Finally, the Irish government amends its

Constitution to remove its territorial claims to Northern Ireland.

The

Nobel Peace Price, which was awarded to John Hume and David Trimble

in 1998, gave the peace process a new momentum. The Nobel

Committee declared Hume, “the clearest and most consistent of

Northern Ireland's political leaders in his work for a peaceful

solution“. As for Trimble, the Committee notes that he “showed

great political courage when, at a critical stage in the process, he

advocated solutions which led to the peace agreement“.

The

third point which can show that things changed was something which

was also negotiated in the agreement and has already been fulfilled

is the accelerated prison release programme, which began in

September. By January 1999 over half of the qualifying

paramilitary prisoners were released. The British authorities began

the process of security normalization, gradually removing security

installations and scaling down the army presence on the ground. The

Northern Ireland Police Commission (under the chairmanship of Chris

Patten) began its work and undertook a wide-ranging consultation

exercise. [compare 31]

4.2

Negative Developments after 1998

But

there were also drawbacks in the time after April 1998 and if

you look at them, you have to say: “No! The expectations did not

came true and the months after the referendum will be remembered as a

time of recrimination, of bitterness, of the sharp word. A period of

missed deadlines, broken agreements, of unfilled opportunity. “

Here

are some good examples for such discouraging incidences, for instance

the innumerable promises of the IRA to decommission. Each time when

Sinn Fein declared that the IRA was ready to give up its guns and

stop terrorism, people hoped the troubles were over but the situation

did not change. In May 2000 the deadline for decommissioning

passed and nothing happened because the IRA did not want to give up

its guns which would have meant the lost of power. The

decommissioning of weapons has been the key stumbling block to full

implementation of the Good Friday Agreement. Disagreement over the

issue led to the suspension of the Northern Ireland Assembly on

February 11th, 2000, which had been established

after elections in June 25th, 1998. Despite furious

last-minute negotiations, no deal was struck on decommissioning, the

“absolute deadline“ which originally was set on June 30th,

1999 and Tony Blair extended it for a few months, passed

without any results and after that, Secretary of State Peter

Mandelson signed the order to suspend the assembly.

As a reaction on the suspension the IRA announced only

four days later, on February 15th that they would no

longer co-operate with the Independent Commission on Decommissioning

because of the suspension of the assembly.

The

basic problem was that David Trimble, the leader of Northern

Ireland's largest party, the Ulster unionists, also refused to

sit on the Executive with Sinn Fein, which has links to the IRA,

until the paramilitaries began to hand over their weapons. On the

other hand, Sinn Fein said decommissioning of weapons was not a

condition of the original peace deal - and it maintained that it

could not promise decommissioning on behalf of the IRA. Furthermore,

UK Prime Minister Tony Blair has given a number of personal

assurances to the unionists, including one in October 1998

that it was his view decommissioning would begin “straight

away“. [compare 63]

4.3

Terrorist Activities after 1998

Looking

at the time after the agreement, everybody had to realize that

terrorism did not stop. The following two examples show the brutality

of the paramilitary groups after April 1998 although the

leaders of all parties tried to achieve peace in Northern Ireland and

were supported by a majority of votes.

The first incidents I would like

to present happened during parades of Protestants who commemorated

King William of Orange and Catholics who tried to prevent the

Protestants from passing through their neighbourhood. The British

government sent extra troops to that area to uphold the decision of

the independent Parades Commission which decided that the parade in

Dumcree would not pass down the Garvaghy Road, a Catholic area.

After July 5th, there

was considerable violence, throughout the province, especially in

Belfast because Protestants were not allowed to march on their

traditional route. Rioters hijacked cars, blockaded streets, and

attacked security forces. Twelve Catholic churches were burned.

On

Sunday, July 12th, 1998 three young catholic

boys were killed after their home, in Ballymoney, was petrol bombed

in a sectarian attack carried out by Loyalists. The boys' mother, her

partner and a family friend escaped from the house but neither they

nor their neighbours were able to rescue the three boys.

The

bombing shocked everyone on both sides and many people called on the

Orangemen in Dumcree to dismantle their camp and go home. David

Trimble, the leader of the Ulster Unionist Party also called for an

end to the protest. The Orange Order rejected these and other similar

calls.

Within the Omagh Bombing about a month later, on August

15th, the single worst terrorist incident in the history

of the troubles occurred. A car bomb exploded in a busy shopping

district in Omagh, a town approximately seventy miles west of

Belfast. Twenty-nine people including several children were killed

and more than 200 were injured. The dead and injured included both

Catholics and Protestants. A splinter group of the IRA called the

“Real IRA“ claimed responsibility for the blast. This tiny

group was opposed to the peace process altogether. After

such terrible events some people feared that these incidents would

derail the peace process. Others were determined not to let that

happen and the people hoped terrorism would stop. [compare 63]

4.4

Further Attempts to Save the Situation

Nevertheless

tried the two sides again and again to discuss the problems and come

to an agreement. On December 10th, 1998, David

Trimble and Gerry Adams held their first one-to-one meeting, in order

to find a solution of the decommissioning problem. This was the first

meeting between Sinn Fein and a Unionist leader since the formation

of Northern Ireland. The meeting took place in private at Stormont,

Belfast. Both men later described the meeting as cordial and

businesslike. Trimble said: “We discussed the issues which are

familiar to you and we examined those issues in a fair amount of

detail. I can’t say there was an awful lot of progress but we

have agreed to meet again” [19]. At the end of the meeting,

there was no concrete result because they could not deliver on

decommissioning. The following meeting also failed and the

participants finished the discussion without a satisfying solution

for both sides.

On

Friday December 18th, 1998 the Agreement on

Government Departments and Cross-Border Bodies was signed. In a

significant breakthrough in the implementation of the Belfast

Agreement, six new North-South administrative bodies and an increase

from six to ten ministries in Northern

Ireland were agreed after 18 hours of negotiations between the

Northern parties. The six North South bodies will cover inland

waterways, agriculture, food safety, the Irish and Ulster-Scots

languages, European Union funding programmes, and trade and business

development.

Furthermore

The Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) handed over some weapons which

should be destroyed to the International Decommissioning Body. The

LVF was the first paramilitary group to voluntarily hand over its

weapons. This gesture was seen as a first real step of

decommissioning but afterwards nothing else happened and the other

groups still refused to give up their guns.

On

Monday September 6th, 1999, George Mitchell, former

Chairman of the multi-party talks, was in Castle Buildings to start

the review of the Good Friday Agreement. He made clear that the

review would concentrate specifically on breaking the deadlock over

decommissioning and the formation of an executive. The talks

adjourned until the following week to give politicians time to study

the Patten report on policing.

After

10 weeks of painstaking negotiations between the pro-agreement

parties in Northern Ireland, Senator George Mitchell returned to the

United States after issuing a report on his review. He concluded that

the basis now existed for devolution to occur and the formation of an

executive to take place. Before leaving Northern Ireland, the senator

was thanked during a press conference in Castle Buildings by all the

participants and parties involved.

The

British Government issued a statement, expressing gratitude for

Senator Mitchell's help in transforming the Northern Ireland

situation from one of conflict and confrontation to one of dialogue

and peace.

On

October 26th, 2000, the IRA released a statement

saying it will allow some of its arms dumps to be re-inspected.

General John de Chastelain of the Decommissioning Commission said

after this inspection that no progress had been made on actual

paramilitary disarmament. [compare 61]

5.

The Role of the US in the Peace Process

The

Northern Ireland Conflict is not only a local problem of the Irish

people, it concerns also politicians all over the world, especially

the USA. The fact that over 40 Million Americans

have Irish roots explains why the United States strove for a peaceful

solution to the Northern Ireland conflict. Most of them immigrated to

America during the Great Famine in the hope for a better life. This

Irish-Americans wanted to help their fellow-countryman who still

lived in war and so wanted a number of US Presidents and the US

Congress.

The interventions from across the Atlantic consisted of political

support during peace negotiations and practical help of the economy

and the reconciliation of the community. The US participation began

with the era of President Carter who promised financial support of a

possible agreement and its implementation and culminated with Bill

Clinton who made in 1992 during his Presidential campaign many

policy-commitments concerning his Administration´s approach to

Northern Ireland. While President Clinton pushed the rapprochement to

Sinn Fein for example by enabling Gerry Adams to visit America which

was never possible in the past he also get in contact with the

Unionists. President Clinton declared Senator George Mitchell his

„economic envoy“ to Ireland as a result of the IRA

cease-fire in August 1994. The Irish people expressed great

gratitude for the support of the United States and the also the wish

for a soon peaceful solution of the conflict through their

extraordinary welcome of President Clinton and his wife Hilary Rotham

Clinton during their historic visit of both parts of Ireland. This

journey in November 1995 was something special because it was

the first visit by a US President in office to Northern Ireland. The

President asked the Republicans for a new attempt to a cease-fire and

played an important role in the Multi-Party Talks which began in June

1996. The American Administration enhanced the search for an

agreement together with the new elected Prime-Ministers of Ireland

and Britain, Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair after the IRA declared a

cease-fire in July 1997 and Sinn Fein supervened the peace

talks in September. Without the Presidents personal diplomacy towards

the end of the talks the historic Good Friday Agreement reached on

April 10th, 1998 would not have been achieved. When

President Clinton met Tony Blair in May 1998 before the

referendum on the Good Friday Agreement he encouraged him: „we

will stand with those who stand for peace. I want to make it clear

that anyone who reverts the violence, from whatever side and whatever

faction will have no friends in America.“ This words expressed

his strong will to fight against all terrorist groups who expect to

enforce a solution with violence.

The interventions from across the Atlantic consisted of political

support during peace negotiations and practical help of the economy

and the reconciliation of the community. The US participation began

with the era of President Carter who promised financial support of a

possible agreement and its implementation and culminated with Bill

Clinton who made in 1992 during his Presidential campaign many

policy-commitments concerning his Administration´s approach to

Northern Ireland. While President Clinton pushed the rapprochement to

Sinn Fein for example by enabling Gerry Adams to visit America which

was never possible in the past he also get in contact with the

Unionists. President Clinton declared Senator George Mitchell his

„economic envoy“ to Ireland as a result of the IRA

cease-fire in August 1994. The Irish people expressed great

gratitude for the support of the United States and the also the wish

for a soon peaceful solution of the conflict through their

extraordinary welcome of President Clinton and his wife Hilary Rotham

Clinton during their historic visit of both parts of Ireland. This

journey in November 1995 was something special because it was

the first visit by a US President in office to Northern Ireland. The

President asked the Republicans for a new attempt to a cease-fire and

played an important role in the Multi-Party Talks which began in June

1996. The American Administration enhanced the search for an

agreement together with the new elected Prime-Ministers of Ireland

and Britain, Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair after the IRA declared a

cease-fire in July 1997 and Sinn Fein supervened the peace

talks in September. Without the Presidents personal diplomacy towards

the end of the talks the historic Good Friday Agreement reached on

April 10th, 1998 would not have been achieved. When

President Clinton met Tony Blair in May 1998 before the

referendum on the Good Friday Agreement he encouraged him: „we

will stand with those who stand for peace. I want to make it clear

that anyone who reverts the violence, from whatever side and whatever

faction will have no friends in America.“ This words expressed

his strong will to fight against all terrorist groups who expect to

enforce a solution with violence.

In

September 1998, the second visit of the President and the

First Lady to Ireland (North and South) occurred and ended as

successful as the first.

The

President availed of this visit and a number of more recent

opportunities to emphasize the continued commitment of the United

States to the achievement of a lasting settlement in Northern

Ireland. All these attempts of Bill Clinton to help Northern Ireland

show how engaged he was in the peace process. [compare 59]

6.

Statements to the Conflict

In

the following paragraph I will try to find out what politicians and

other people involved in the Northern Ireland Conflict say about the

Good Friday Agreement and the Peace Process as a whole.

At

the beginning there are some statements of the British Prime Minister

Tony Blair. The Electronic Telegraph quoted Mr. Blair on Saturday,

April 11th, 1998, saying: “I believe today

courage has triumphed. I said when I arrived here that I felt the

hand of history upon us. Today I hope that the burden of history can

at long last start to be lifted from our shoulders.“ He referred

to the Agreement and expressed his hope that after this Good Friday

Peace Accord it would be possible to bring the war to an end. He also

emphasized that the agreement represented an opportunity for peace

in Northern Ireland and that much difficult work laid ahead. He said:

“It will take more of the courage we have shown, but it need not

mean more of the pain. Today is only the beginning. It is not the

end. Today we have just the sense of the prize before us. The work to

win that prize goes on. In the past few days the irresistible force

of the political leaders has been focused on that same immovable

object. I believe we have now moved it.“ [13]

Peter

Mandelson, the British minister for Northern Ireland said in an

interview of the “Chicago Tribune“ on October 15th,

2000: “There has been a transformation since the signing

of the Good Friday Agreement. We have cease-fires that are largely

intact, a peace which, though not perfect, is enduring. But we have

an infant democracy, a set of political institutions that are

fragile. If these changes lose the backing of one [religious]

tradition or another, then the peace process will stop. Therefore,

the spirit of compromise has to be maintained. We're in transition in

Northern Ireland from one era to another. We haven't yet arrived.

Dissident Republicans are determined to continue with violence and

terrorism, or loyalist dissidents are determined to feud among

themselves.” [77]

US

Senator Mitchell, the peace talks chairman, was quoted in the “Irish

News” on November 30th, 1998 during his visit

in Belfast saying: “It is unrealistic to think that a conflict

which is as long and as complex as this one could suddenly be ended

with the approval of a single document. I think the direction is

set." Gerry Adams met Mr Mitchell at that time and he said in

this interview with the “Irish News”: “At the moment I

think that everyone is ready to close on the implementation of

policy-making bodies, but the senator knows that there is still a lot

of movement needed on many fronts and I will be discussing these

issues with him.” [86]

David

Trimble was quoted in an article of the “BBC news online”

from January 8th, 2000 being sceptical about the

process but he said; “I'm quite confident about arrangements and

I'm quite confident about the future. And I've said ever since the

agreement that things are not going to be easy, that there are going

to be problems and we have had problems. But we have also had

enormous progress since the agreement, and I look forward to the

coming weeks and months with considerable confidence." [7]

Education

Minister Martin McGuinness was also quoted in the same article

talking about decommissioning and he said: “We're all on board

the same boat now and we've moved away from the berthing post. We're

still in the harbour but we're moving forward - I think anyone who

jumps off at this stage will be drowned.” He added: “We've

charted a course away from the injustice, the causes of conflict and

conflict itself - we have to stay on this course.” [7]

These

few quotations show that on the other hand all politicians from

different parties and even from different countries try to find a

solution for the conflict which satisfies both sides and want to

implement the agreement as quickly as possible. On the other hand all

of them know that it is not easy to find a result for all issues and

problems. Sometimes you can hear voices saying that it makes no sense

to hope for peace and nothing will move in the problem of

decommissioning, like in the article of “The Irish Times”

published on Tuesday April 13th, 1999 where the

mood was very depressive and negative. Members of Sinn Fein were

quoted saying things like: ”We have accepted compromises in the

past for the sake of peace, but decommissioning is different. They

are asking us to surrender. You can't underestimate the emotiveness

of this subject for republicans.” [12] Another quotation which

shows how ironic some people react to the peace process is the

following, also published in the same article: ”The guns are

silent so what is the problem for the unionists and the British? They

just seem to want to rub our noses in the dirt." [12] It is hard

to explain such people what the real aims of the Good Friday

Agreement are because they are to pigheaded.

As a

conclusion you can say that all statements concerning the peace

talks, the agreement and the Northern Ireland Conflict as a whole

given by politicians and people who know the problems or have to live

with it are more or less positive and optimistic. They know that it

is still a long way till the situation will be totally different and

Northern Ireland will live in peace but all in all they will try to

find a solution.

7.

Personal Opinion

By

dealing for several months with the topic “Northern Ireland

Conflict”, I reached a better insight into the situation of

Northern Ireland. And now, after finishing my work it may be a little

bit easier to understand what is going on in this country and why all

the problems still exist for 30 years. During my investigation I

learned something about the background of the conflict, about the

differences of catholics and protestants, about the issues and

problems which have to be solved in order to achieve peace between

the two hostile groups and about the attempts which were and still

are made by politicians from both sides to find a satisfying solution

for all of them.

Although

I read very much about this topic it is hard for me to comprehend why

these people cannot find a way to make an end to this endless war.

This conflict runs so deep that a foreigner is hardly able to

understand the whole extent of the problems. In my opinion

politicians and especially the few terrorist groups who try to solve

the problems with violence have to change their attitudes. Peace can

only come if both sides learn to trust each other. Someone has to

make the first step, for example in decommissioning and the other

side has to follow. As long as decommissioning is a stumble stone in

the peace process, the war will not come to an end. Moreover people

have to learn to compromise, to be more tolerant and to accept also

other views.

The

“Good Friday Agreement” of 1998 was an excellent

beginning for the peace process, but it is still a long way until all

the points of the agreement are fully implemented and it will require

much efforts to reach the aim of the agreement. In my view it is not

impossible that the next generations will live in peace together but

the parents have to tell their children that it is not so important

to what religion you belong or what your political attitude is, but

that we are all human beings who live on the same earth and breath

the same air and we should not fight against each other because in

the end no one is the winner, there are only loosers, who share the

same sorrows.

1. Introduction

1. Introduction This area adopted English administrative practices, the

English language and was looking to London for protection and

leadership. In the next decades some attempts were made in order to

extend English control over the rest of Ireland but they did not

succeed until the 16th century. In 1609,

military conquest had established English rule over most of

Ireland with the exception of Ulster. The province had succeeded in

creating an effective alliance against the foreign armies but after a

lot of fights the Irish were defeated and had to give up. Ulster was

brought under English control and British colonists confiscated and

distributed the land among themselves. By 1703, less than 5

per cent of the land of Ulster was still in the hand of the Irish.

[compare 4]

This area adopted English administrative practices, the

English language and was looking to London for protection and

leadership. In the next decades some attempts were made in order to

extend English control over the rest of Ireland but they did not

succeed until the 16th century. In 1609,

military conquest had established English rule over most of

Ireland with the exception of Ulster. The province had succeeded in

creating an effective alliance against the foreign armies but after a

lot of fights the Irish were defeated and had to give up. Ulster was

brought under English control and British colonists confiscated and

distributed the land among themselves. By 1703, less than 5

per cent of the land of Ulster was still in the hand of the Irish.

[compare 4] The Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday

Agreement) was reached on Friday, April 10th, 1998

in Belfast. It was the result of multi-party negotiations where all

people of the different parties in Northern Ireland tried to find a

way to co-operate in order to achieve a durable peace concept for

Northern Ireland after 30 years of war and terrorism. The most

important members who joined the negotiations were:

The Belfast Agreement (also known as the Good Friday

Agreement) was reached on Friday, April 10th, 1998

in Belfast. It was the result of multi-party negotiations where all

people of the different parties in Northern Ireland tried to find a

way to co-operate in order to achieve a durable peace concept for

Northern Ireland after 30 years of war and terrorism. The most

important members who joined the negotiations were: The time after the referendum on May 22nd,

where the majority of people in the North and the South voted with

“yes“ on the agreement (in Northern Ireland 71.2% of the

voters and in the Republic of Ireland 94% voted “yes”)

[26] could have been a period during which the letter and the spirit

of the Good Friday Agreement was fully utilized, a period when Irish

nationalists, unionists and the British moved towards each other in

an effort to put behind them the enmity resulting from centuries of

conflict.

The time after the referendum on May 22nd,

where the majority of people in the North and the South voted with

“yes“ on the agreement (in Northern Ireland 71.2% of the

voters and in the Republic of Ireland 94% voted “yes”)

[26] could have been a period during which the letter and the spirit

of the Good Friday Agreement was fully utilized, a period when Irish

nationalists, unionists and the British moved towards each other in

an effort to put behind them the enmity resulting from centuries of

conflict.

The interventions from across the Atlantic consisted of political

support during peace negotiations and practical help of the economy

and the reconciliation of the community. The US participation began

with the era of President Carter who promised financial support of a

possible agreement and its implementation and culminated with Bill

Clinton who made in 1992 during his Presidential campaign many

policy-commitments concerning his Administration´s approach to

Northern Ireland. While President Clinton pushed the rapprochement to

Sinn Fein for example by enabling Gerry Adams to visit America which

was never possible in the past he also get in contact with the

Unionists. President Clinton declared Senator George Mitchell his

„economic envoy“ to Ireland as a result of the IRA

cease-fire in August 1994. The Irish people expressed great

gratitude for the support of the United States and the also the wish

for a soon peaceful solution of the conflict through their

extraordinary welcome of President Clinton and his wife Hilary Rotham

Clinton during their historic visit of both parts of Ireland. This

journey in November 1995 was something special because it was

the first visit by a US President in office to Northern Ireland. The

President asked the Republicans for a new attempt to a cease-fire and

played an important role in the Multi-Party Talks which began in June

1996. The American Administration enhanced the search for an

agreement together with the new elected Prime-Ministers of Ireland

and Britain, Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair after the IRA declared a

cease-fire in July 1997 and Sinn Fein supervened the peace

talks in September. Without the Presidents personal diplomacy towards

the end of the talks the historic Good Friday Agreement reached on

April 10th, 1998 would not have been achieved. When

President Clinton met Tony Blair in May 1998 before the

referendum on the Good Friday Agreement he encouraged him: „we

will stand with those who stand for peace. I want to make it clear

that anyone who reverts the violence, from whatever side and whatever

faction will have no friends in America.“ This words expressed

his strong will to fight against all terrorist groups who expect to

enforce a solution with violence.

The interventions from across the Atlantic consisted of political

support during peace negotiations and practical help of the economy

and the reconciliation of the community. The US participation began

with the era of President Carter who promised financial support of a

possible agreement and its implementation and culminated with Bill

Clinton who made in 1992 during his Presidential campaign many

policy-commitments concerning his Administration´s approach to

Northern Ireland. While President Clinton pushed the rapprochement to

Sinn Fein for example by enabling Gerry Adams to visit America which

was never possible in the past he also get in contact with the

Unionists. President Clinton declared Senator George Mitchell his

„economic envoy“ to Ireland as a result of the IRA

cease-fire in August 1994. The Irish people expressed great

gratitude for the support of the United States and the also the wish

for a soon peaceful solution of the conflict through their

extraordinary welcome of President Clinton and his wife Hilary Rotham

Clinton during their historic visit of both parts of Ireland. This

journey in November 1995 was something special because it was

the first visit by a US President in office to Northern Ireland. The

President asked the Republicans for a new attempt to a cease-fire and

played an important role in the Multi-Party Talks which began in June

1996. The American Administration enhanced the search for an

agreement together with the new elected Prime-Ministers of Ireland

and Britain, Bertie Ahern and Tony Blair after the IRA declared a

cease-fire in July 1997 and Sinn Fein supervened the peace

talks in September. Without the Presidents personal diplomacy towards

the end of the talks the historic Good Friday Agreement reached on

April 10th, 1998 would not have been achieved. When

President Clinton met Tony Blair in May 1998 before the

referendum on the Good Friday Agreement he encouraged him: „we

will stand with those who stand for peace. I want to make it clear

that anyone who reverts the violence, from whatever side and whatever

faction will have no friends in America.“ This words expressed

his strong will to fight against all terrorist groups who expect to

enforce a solution with violence.