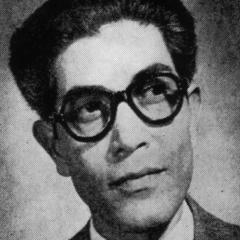

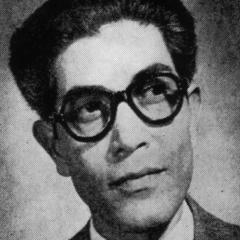

Professor Ahmed Ali was born in Delhi in 1910, and educated at Aligarh and Lucknow universities, standing first-class and first in the order of merit in both B.A. (Honours), 1930 and M.A. English, 1931. He taught at leading Indian universities including Lucknow and Allabbad from 1932-46 and joined the Bengal Senior Educational Service as Professor and Head of the English Department at Presidency College, Calcutta (1944-47). Professor Ahmed Ali was also BBC's Representative and Director in India during 1942-44. He went to China in 1947 as British Council Visiting Professor of English at the National Central University at Nanking. There, he learnt Chinese and translated from Chinese poets, and gathered material for his book Muslim China ; his house became a gathering of friends and China his second home. A year later India was divided and he came from China to Karachi in 1948; becoming Director of Foreign Publicity, Government of Pakistan. He joined the Pakistan Foreign Service at the insistence of Mr. Liaquat Ali Khan, and the first file he received was marked "China" but was blank. He successfully  established diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic of China in record time and the Pakistani embassy in Peking in 1950; and the Embassy in Morocco, in 1958. With Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Surahwardy he visited China again in 1956.

established diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic of China in record time and the Pakistani embassy in Peking in 1950; and the Embassy in Morocco, in 1958. With Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Surahwardy he visited China again in 1956.

Professor Ahmed Ali started his literary career at a very young age and became co-founder of the All-India Progressive Writers' Movement and Association with the publication of Angare in 1932, a collection of short stories by four young friends, which was later banned by the British Government of India in March of 1933. Shortly afterwards Ahmed Ali and  Mahmud-uz-Zaffar announced the formation of a "League of Progressive Authors", which was later to expand and become the All-India Progressive Writers' Association. Ahmed Ali presented his paper Art ka Taraqqi-Pasand Nazariya in its lnaugural Conference in 1936. A pioneer of the modem Urdu short story, Ahmed Ali's works include collections of short stories: Sholay (1934); Hamari Gali (1940); Qaid Khana (1942); and Maut Se Pahle (1945).

Mahmud-uz-Zaffar announced the formation of a "League of Progressive Authors", which was later to expand and become the All-India Progressive Writers' Association. Ahmed Ali presented his paper Art ka Taraqqi-Pasand Nazariya in its lnaugural Conference in 1936. A pioneer of the modem Urdu short story, Ahmed Ali's works include collections of short stories: Sholay (1934); Hamari Gali (1940); Qaid Khana (1942); and Maut Se Pahle (1945).

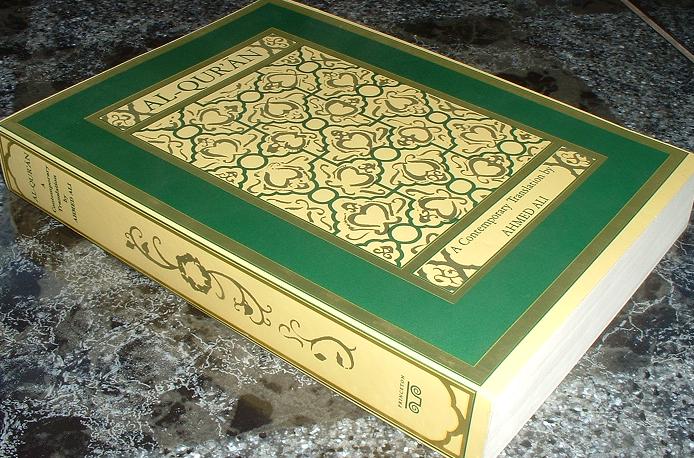

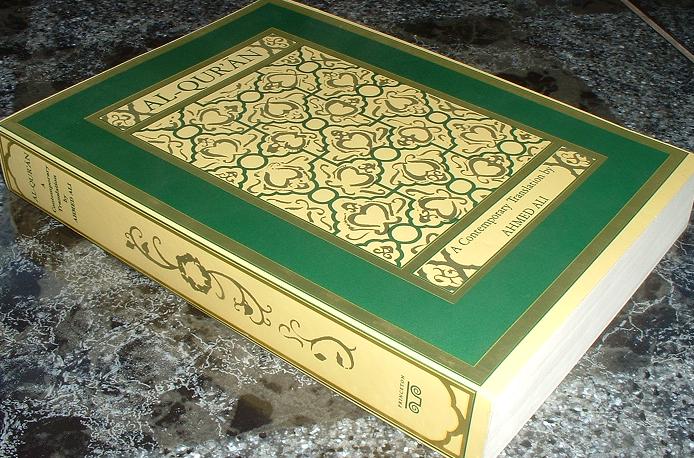

Al-Qur'an: A Contemporary Translation Princeton University Press , Oxford University Press & Akrash</ref> is Ahmed Ali's most outstanding contribution in the field of translation. Approved by eminent Islamic scholars , it has come to be recognised as the best of existing translations of the holy Qur'an . In the words of Dr. F. E. Peters of New York University : "Ahmed Ali's work is clear, direct, and elegant - a combination of stylistic virtues almost never found in translations of the Qur'an. His is the best I have read."

Professor Ahmed Ali was a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Humanities at Michigan State University in 1975, Fulbright Visiting Professor of History at Western Kentucky University and Fulbright Visiting Professor of English at Southern Illinois University in 1978-79. He was made an Honorary Citizen by the State of Nebraska in 1979. He was Visiting Professor at the University of Karachi during 1977-79, which later conferred on him an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature in 1993.

A distinguished gentleman of refined taste and manners, Professor Ahmed Ali had a deep interest in Sufism and a passion for Ghalib. His writings voiced concern over the decay of Muslim culture and the injustices of colonial powers. Proficient in several languages including French, Chinese, Persian and Qur'anic Arabic, he captivated audiences by his eloquent speech and expression. Steeped in tradition but progressive at heart, he was equally at home in the East and the West. Professor Ahmed Ali had travelled widely, and was an avid collector of Chinese porcelain and paintings, Gandhara art and other antiques. He rubbed shoulders with kings and dignitaries and among his circle of friends were E. M. Forster, George Orwell, Virginia Wolf and the Bloomsbury Group, Han Su Yin, Tien Chen, Sarojini Naidu, Laxmi Pandit, Raja Rao, Jamni Roy, Kunwar Natwar Singh and the Surahwardy family; Mohsin Abdullah and Laurence Brander from Aligarh and Lucknow were his dear friends to the end.

Professor Ahmed Ali's career spanned the better part of the 20th century and he put the people of Pakistan in touch with both their past and present. His renderings of literatures of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Far East established links which were not yet known, and are remembered respectfully. His creative writings draw wide interest and are an enduring contribution to international letters. He was elected a Founding Fellow of the Pakistan Academy of Letters in 1979 and was awarded the Sitara-i-lmtiaz in 1980 in recognition of his contribution to letters and the nation.

Professor Ahmed Ali died in Karachi on 14th January 1994.

During the 1950s Ahmed Ali worked for the Pakistan Foreign Service, establishing embassies in Morocco and China .

- Zeno (1994). "Professor Ahmed Ali and the Progressive Writers' Movement" (pasted below). Annual of Urdu Studies 9 : 39–43. ISSN: 0734-5348. Retrieved on 2006 - 12-02 .

- Mahmud, Shabana (May 1996). "Angare and the Founding of the Progressive Writers' Association". Modern Asian Studies 30 (2): 39–43.

- Ali, Ahmed (1974), "The Progressive Writers Movement and Creative Writers in Urdu", in Carlo Coppola, Marxist Influences and South Asian Literature , East Lansing: Michigan State University, ISBN 81-7001-011-X

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ahmed Ali Scholar, poet, teacher, and diplomat Ahmed Ali (1908-1998) holds an honored place as novelist and chronicler of India's shift from an English colony to a free state. In addition to being a prolific author of poems and world-class novels, translator of the Koran and the ghazals of Ghalib, and critic of poet T. S. Eliot, Ali lived a double life in business and politics. He worked as a public relations director and was a foreign spokesman for Pakistan. While serving in the diplomatic corps, he traveled the world.

The son of Ahmad Kaniz Begum and Syed Shujauddin, a civil servant, Ali was born in Delhi, India, on July 1, 1908. He grew up during the emergence of Indian nationalism and the Muslim League, the impetus behind the creation of a separate state of Pakistan. After his father's death, he passed into the care of conservative relatives who lived under a medieval set of standards. According to their orthodox views, Ali could not read poetry or fiction in Urdu, even the classic fable collection The Arabian Nights, which they denounced as immoral .

Escape Through Reading

To flee intellectual isolation, Ali read a volume of children's fables - Charles Kingsley's The Water-Babies: A Fairy Tale for a Land-Baby (1863) - and began writing his own fiction around the age of eleven. For material, he adapted adventure stories and tales he heard from his aunts and from storytellers. In his teens, he expanded his reading experience to European novelists James Joyce, D. H. Lawrence, and Marcel Proust and the verse of revolutionary English poet T. S. Eliot.

An Intellectual in the Making

During Ali's youth, the era was gloomy with upheaval as India struggled to free itself from British colonialism. At this momentous time in the nation's transformation, from 1925 to 1927, he attended Aligarh Muslim University in southeast Delhi. After transferring to Lucknow University, where he completed a B.A. and M.A. with honors, he thrived in an academic community and enjoyed the atmosphere of the King's Garden and the River Gomti. He was influenced by socialist and communist doctrines and gained the camaraderie of British and Indian professors, who admired his candor .

Ali channeled his idealism into political activism. The rise of the freedom movement that followed the Simon Commission Report on Indian Reforms stressed the nation's need for total change. He recognized that Indians lived a shallow existence that perpetuated failed ideals adopted from their British overlords. He realized that the people's reliance on religion and fatalism worsened slavery, hunger, and other remnants of imperialism.

After graduating in 1931, Ali earned his living by lecturing in English at Lucknow, Allahabad, and Agra universities. Choosing Urdu, the language of the Progressive Writers' Movement, he simultaneously began writing short fiction. He collaborated with three friends to publish a first pro-revolution anthology, Angaray (Burning Coals), which earned the scorn of conservatives and Islamic fanatics. In addition to ridiculing the authors, his critics threatened them with death by stoning. Three months later, agitators caused the British government to ban the book. In response to censorship, Ali maintained hope for the future through literature. To advance Indian reform, he helped to found the Progressive Writers' League and dedicated himself to a literary life.

Finding a Voice

For the next twelve years, Ali wrote short stories, some of which reached English and American readers in translation. His experiments with symbolism, realism, and introspection helped to direct the modern Urdu short story. He followed the joint fiction collection with his own anthology, Sholay (Flames) (1932) and two plays, Break the Chains (1932) and the one-act The Land of Twilight (1937). In 1936, he co-founded the All-India Progressive Writers Association, the preface to a new era in Urdu literature. The league's internal squabbles over progressivism caused a break with orthodox members. Opposed to stodgy conservative proponents of the working class, he chose a more inclusive, humanistic world view.

To reach more readers, Ali abandoned Urdu in favor of English. In 1939, he produced his masterwork, Twilight in Delhi, the saga of an upper-class Muslim merchant and his family during and after the 1857 mutiny , India's first war of independence. In an act of personal and ethnic introspection, Ali locked himself in his apartment and composed fiction that exposed his homeland's social problems. He believed that India was trapped in an inescapable low, an historic ebb that was part of a universal cycle of rise and fall, birth and decay. He stressed the powerlessness of human actors caught up in events orchestrated by invisible forces.

At the beginning of World War II, Ali carried his novel manuscript to London and sold it to Hogarth Press . After editorial clashes over themes the staff considered subversive , the company issued his book in 1940. It found immediate favor with critics Bonamy Dobree, E. M. Forster, and Edwin Muir. When a later edition reached American audiences in 1994, Publishers Weekly called it a fascinating history and cultural record of India.

A Taste of Success

When Ali returned home, he had become a legend. His novel was a popular favorite that All-India Radio broadcast to listeners. Still much in demand, it has become a classic of world literature. He turned to scholarly writing and published Mr. Eliot's Penny World of Dreams: An Essay in the Interpretation of T. S. Eliot's Poetry (1941).

During World War II, Ali worked for the British Broadcasting Corporation in Delhi as representative and listener research director. He continued writing short stories and issued three Urdu collections: Hamari Gali (1944), Maut se Pahle (1945), and Qaid Khana (1945). In the late 1940s, he headed the English department at Presidency College in Calcutta and was visiting professor for the British Council in Nanking at the National Central University of China. The next year, he resided in Karachi and directed foreign publicity for the government of Pakistan.

Restored Initial Aims

Ali discovered that his academic and civic work was not conducive to the demands of writing. Retreating to the solitude of the Kulu Valley in the Himalayas, he followed his first novel with Ocean of Night, a sequel set between the world wars and depicting the 1947 split of the Indian state into India and Pakistan. Sensitive to the hardships that reform placed on individual citizens, the text focused on India's loss of traditions and the new and uncharted direction that his fellow Indians faced.

During a reflective period, Ali worked for twelve years as counselor and deputy ambassador in the diplomatic service and resided in China, England, Morocco, and the United States. In traveling over four continents, he encountered new mindsets and attitudes. He composed Muslim China (1949) for the Pakistan Institute of International Affairs and translated The Flaming Earth: An Anthology of Indonesian Poetry (1949) and The Falcon and the Hunted Bird (1950). These translations introduced the English-speaking world to classic Urdu verse.

Family life also competed for Ali's attention. In 1950, he married Bilqees Jehan Rant, mother of their sons Eram, Orooj, and Deed and a daughter, Shehana. In 1960, he began supporting his family by directing public relations for business and industry. On the side, he collected verse for Purple Gold Mountain: Poems from China (1960) and translated and edited The Bulbul and the Rose: An Anthology of Urdu Poetry (1960). In 1964, he returned to his second novel and published it.

When Ali again scheduled time for intensive writing, he edited Under the Green Canopy: Selections from Contemporary Creative Writings from Pakistan (1966). He also produced bilingual Italian-Urdu short fiction entitled Prima della Morte (1966) and composed The Failure of an Intellect (1968) and Problems of Style and Technique in Ghalib (1969). In addition, he translated Ghalib: Selected Poems (1969), the ghazals of early 19th-century poet Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib of Agra. As India's socio-political obsessions shifted from secular to religious, Ali found an absorbing set of problems to ponder . These challenges formed the plot of a third novel, Rats and Diplomats, a fictional canvas stripped of old themes and motifs. He completed it in 1969, but withheld it from publication until 1985.

Balanced Work and Art

In this second waiting period, Ali worked as deputy director for the United Kingdom Immigrants Advisory Service and chairman of Lomen Fabrics, Ltd., until 1978. He also translated The Golden Tradition: An Anthology of Urdu Poetry (1973) and published a critical volume, The Shadow and the Substance: Principles of Reality, Art and Literature (1977). Retired from business, he lectured at Michigan State and Karachi University and served Western Kentucky and Southern Illinois universities as Fulbright visiting professor.

Still driven to write fiction that illuminated India's growth pangs, Ali pursued his career for internal reasons rather than for royalties. Working twelve-hour days at his home in Karachi, he created stories that expressed his joy in national advances and that taught the new generation about the forces that brought India into the modern age. In 1980, he received Pakistan's Sitara-e-Imtiaz (Star of Distinction), his most treasured award.

In his 70s, Ali issued a contemporary bilingual edition of the Koran, which critic Edwin Muir applauded for its pictorial elegance, rhythm, and spiritual power. He continued to produce short stories and verse and published The Prison-House (1985) and Selected Poems (1988). His collection of antiques, Gandhara art , and Chinese porcelain allowed him moments of relaxation. The University of Karachi presented him an honorary degree in 1993. Ali died on March 19, 1998, in Stockport , England.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

PROFESSOR AHMED ALI was born in Delhi in 1910, and educated at Aligarh and Lucknow universities, standing first-class and first in the order of merit in both B.A. (Honours), 1930 and M.A. English, 1931.

Professor Ahmed Ali taught at leading Indian universities including Lucknow and Allabbad from 1932-46 and joined the Bengal Senior Educational Service as Professor and Head of the English Department at Presidency College, Calcutta (1944-47). Professor Ahmed Ali was also BBC's Representative and Director in India during 1942-44. He went to China in 1947 as British Council Visiting Professor of English at the National Central University at Nanking. There, he learnt Chinese and translated from Chinese poets, and gathered material for his book Muslim China; his house became a gathering of friends and China his second home. A year later India was divided and he came from China to Karachi in 1948; becoming Director of Foreign Publicity, Government of Pakistan. He joined the Pakistan Foreign Service at the insistence of Mr. Liaquat Ali Khan, and the first file he received was marked "China" but was blank. He successfully established diplomatic relations with the Peoples Republic of China in record time and the Pakistani embassy in Peking in 1950; and the Embassy in Morocco, in 1958. With Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Surahwardy he visited China again in 1956.

Professor Ahmed Ali started his literary career at a very young age and became co-founder of the All-India Progressive Writers' Movement and Association with the publication of Angare in 1932, a collection of short stories by four young friends, which was later banned by the British Government of India in March of 1933. Shortly afterwards Ahmed Ali and Mahmud-uz-Zaffar announced the formation of a "League of Progressive Authors", which was later to expand and become the All-India Progressive Writers' Association. Ahmed Ali presented his paper Art ka Taraqqi-Pasand Nazariya in its lnaugural Conference in 1936. A pioneer of the modem Urdu short story, Ahmed Ali's works include collections of short stories: Sholay (1934); Hamari Gali (1940); Qaid Khana (1942); and Maut Se Pahle (1945).

Ahmed Ali achieved international fame with his novel Twilight in Delhi , which was first published by The Hogarth Press in London in 1940. It was widely acclaimed by critics, and hailed in India as a major literary event, and took the English speaking world by storm. It has since acquired the position of a legend. The leading critic, Maurice Collis, in Time and Tide of London wrote: "It may well be that we may not understand India until it is explained to us by Indian novelists of the first ability as it was that we understood nothing of Russia before we read Tolstoy, Turgenev and the others. Ahmed Ali may well be the vanguard of such a literary movement." This judgement was reechoed by the Oxford History of India in 1958 when it said in reference to Ahmed Ali, Mulk Raj Anand and R.K. Narayan: "... it can be said that they have taken over from E.M. Forster and Edward Thompson the task of interpreting modern India to itself and the world." Twilight in Delhi has been translated into many languages including French, Spanish and Italian. Its exemplary Urdu translation, Dilli ke Sham (1963), by Professor Ahmed Ali stalented wife, Bilqees Jehan, in the opinion of some critics restored the natural language to the book, but those who read it in the translation said it could not have been written in English while those who had read it in the original English said it was untransiatable. This curious controversy was put to an end by the American critic, Dr. David D. Anderson, when he said: "the novel transcends language as any substantial work of art ultimately must do…".

Ahmed Ali's other works include two novels, Ocean of Night and Of Rats and Diplomats; The Prison-House; Purple Gold Mountain; Selected Poems; Mr. Eliot's Penny-world of Dreams; Muslim China; Ghalib: Selected Poems, The Problem of Style and Technique in Ghalib; and The Flaming Earth . Professor Ahmed Ali translated from Urdu, Persian, Indonesian, Chinese and Arabic. His translation of classical Urdu poetry, The Golden Tradition (Columbia University Press, 1973), makes an important contribution to the study of comparative literatures, and surveys in depth the literary and philosophical background of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries.

AI-Qur'an, A Contemporary Translation (Princeton University Press, Oxford University Press & Akrash) is Professor Ahmed Ali's most outstanding contribution in the field of translation. Approved by eminent Islamic scholars, it has come to be recognised as the best of existing translations of the holy Qur'an. In the words of Dr. F. E. Peters of New York University: "Ahmed Ali's work is clear, direct, and elegant - a combination of stylistic virtues almost never found in translations of the Qur'an. His is the best I have read."

Professor Ahmed Ali was a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Humanities at Michigan State University in 1975, Fulbright Visiting Professor of History at Western Kentucy University and Fulbright Visiting Professor of English at Southern Illinois University in 1978-79. He was made an Honorary Citizen by the State of Nebraska in 1979. He was Visiting Professor at the University of Karachi during 1977-79, which later conferred on him an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature in 1993.

A distinguished gentleman of refined taste and manners, Professor Ahmed Ali had a deep interest in sufism and a passion for Ghalib. His writings voiced concern over the decay of Muslim culture and the injustices of colonial powers. Proficient in several languages including French, Chinese, Persian and Qur'anic Arabic, he captivated audiences by his eloquent speech and expression. Steeped in tradition but progressive at heart, he was equally at home in the East and the West. Professor Ahmed Ali had travelled widely, and was an avid collector of Chinese porcelain and paintings, Gandhara art and other antiques. He rubbed shoulders with kings and dignitaries and among his circle of friends were E. M. Forster, George Orwell, Virginia Wolf and the Bloomsbury Group, Han Su Yin, Tien Chen, Sarojini Naidu, Laxmi Pandit, Raja Rao, Jamni Roy, Kunwar Natwar Singh and the Surahwardy family; Mohsin Abdullah and Laurence Brander from Aligarh and Lucknow were his dear friends to the end.

Professor Ahmed Ali's career spanned the better part of the 20th century and he put us in touch with both our past and our present. His renderings of literatures of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Far East established links which were not yet known, and are remembered respectfully. His creative writings draw wide interest and are an enduring contribution to international letters. He was elected a Founding Fellow of the Pakistan Academy of Letters in 1979 and was awarded the Sitara-i-lmtiaz in 1980 in recognition of his contribution to letters and the nation.

Professor Ahmed Ali died in Karachi on 14th January 1994.

(Courtesy: Orooj Ahmed Ali and Shahana Ahmed Ali)

Professor Ahmed Ali and the

Progressive Writers’ Movement

Professor Ahmed Ali's death last week spelt the end of a legend—the

legend of Angar, a book of short stories by four friends who together

came to be known as the earliest initiators of the Progressive Writers’

Movement (PWM) in Urdu literature. The other three writers were Syed

Sajjad Zaheer, Mahmuduzzafar, and Rashid Jahan. They had all died

many years before Ahmed Ali breathed his last some days ago. While

Zaheer, Zafar, and Jahan continued to be associated with the PWM quite

unambiguously over the last sixty years, Professor Ahmed Ali’s position in

it became somewhat confused a few years after its official beginning in

1936. His friends remembered him as one of them because of his

participation in the Angar group, but they also regretted that he had

parted company with them after some time.

The opponents of the Progressive Writers (PW) emphasized Ahmed

Ali’s renunciation, as they called it, from the mainstream of the

Movement and regarded it as a sign of its failure and ideological poverty.

For many years, they continued to be thrilled at the discomfiture of the

Progressives due to Ahmed Ali’s “betrayal,” until he himself issued a

rejection of any such renunciation or “betrayal.”

In the Afterword of The Prison-House, an English language

translation of his short stories (1986), Ahmed Ali gave his version of his

relationship with Progressivism, at once different from the versions of the

opponents of the PWM as well as its official proponents. Ahmed Ali

maintained that he had continued to be a progressive writer throughout

his life, ever since his participation in the activities of the Angar group in 1932 –33, the original sponsors of the PM.

Abriged; courtesy of Dawn (February, 1994); originally published as “In

Memory of Prof. Ahmed Ali.”

In his own words:

The publication of Angaray (Burning Coals) in December 1932

was followed by an all-India agitation against the book and its

authors […] by reactionary parochial forces. As a result Sajjad

Zaheer disappeared from the scene, and took up residence in

London as early as February or March 1933. The book was banned

soon after by the government of India. On fifth April 1933 we

published our “Defence of Angaray” statement announcing the

formation of the League of Progressive Authors, which was

renamed in 1936 “All India Progressive Writers’ Association.” Our

statement was, thus, the first manifesto, as Angaray was its first

manifestation. (p. 164)

Ahmed Ali was not only one of the signatories of the first manifesto

of 5 April 1933, but also one of the most active participants of the All-

India Progressive Writers’ Association (AIPWA) in 1936. This was

acknowledged by Sajjad Zaheer long afterwards in Råshn≥’μ—a semiofficial

history of Progressive Writers Association (PWA)—in which it has

been stated that in 1936 Ahmed Ali’s house in Allahabad became the

office of the proposed movement.

He actively participated in the first Progressive Writers Conference in 1936 and also in the second in Calcutta two years later, besides working

on the editorial board of New Indian Literature, the English language

organ of the AIPWA, published in 1939. In the first issue of this

magazine, he contributed a translation of Premchand’s famous short story “Kafan” (The Shroud).

This establishes incontrovertibly that not only was Ahmed Ali an

initiator of the PM because of his association with the Angar group in

1932–33 but had also continued to be a participant in the activities of the

AIPWA at least until 1939. His short stories “Hamari Gali” (Our Lane)

and “Mera Kamra ” (My Room) were both published in the Association’s

official Urdu organ Naya Adab (New Literature) published from

Lucknow.

Ahmed Ali’s claim to have been, and to have continued to be, a progressive

writer is not proved merely by his organizational and participatory

association with the PM in 1932, 1936, 1938 and 1939; it is also

proved through the general drift of his writing. For instance, in such

stories as “Hamari Gali” and “Mera Kamra,” we find him ideologically and

politically identifying himself with the general trend that Progressive writing assumed in the 1930s and later.

There are two basic characteristics in his writing that establish his

identity as a progressive writer. Firstly, in the formal aspect of his fiction,

he appears to be a strict realist who is concerned above all with the social

reality of his group [sic —Eds.] Secondly, in terms of content, he comes

off as an astute and unremitting satirical critic of the life of his society

who passionately upholds the cause of social change. Both these characteristics

endure throughout in his writing, indeed till the very end. These

twin characteristics of realism and social criticism defined the nature of

Urdu progressive writing in its heyday.

In western countries, where realism originated in the nineteenth

century, it stood for a kind of literary activity aiming at the faithful

depiction of the life of the individual in society as it actually was, not as it

ought to be, or as it was imagined to be in romances and allegories.

The emphasis on the role of literature as a mirror of society next led

the nineteenth-century European writers to turn it into an instrument of

social criticism. Dickens and Thackeray in England; Balzac, Stendhal and

Flaubert in France; and Gogol, Pushkin, Turgenev, Tolstoy and

Dostoevsky in Russia depicted the reality of their changing societies with

all the ugly features of economic, social and political degradation which

characterized them.

Urdu prose writers at the beginning of the twentieth century were, by

and large, unaware of the changes in literary activity and purpose that

were taking place among the European writers. But by the end of the

First World War they could be said to have caught up with those

changes.

Along with the awareness of a new mode of writing—realism,

especially connected with social criticism—the Urdu writer found himself

in the midst of a political storm in his society, a storm whipped up by a

set of freshly-introduced political ideas. Anti-imperialism, national independence,

social revolution—these ideas possessed the consciousness of

people everywhere. The end of the First World War found the Muslim

people locked into a bitter confrontation with tyranny and imperialist

exploitation everywhere. The Russian socialist revolution worked as an

explosive ideological force among the younger generation. These crisscrossing

patterns of political and social dynamism, and the national

revolutionary struggle going on in India itself, awakened the Urdu writer,

as they did the writers of other Indian languages, to the new realities of

life that ran counter to the traditional views of their forefathers as much

as to the preferences of their colonial masters and the latter’s followers among the indigenous people.

It was these social, economic, and political factors, both at home and

abroad, that helped forge a new literary consciousness in Urdu, the PWA

being its most organized expression throughout the fourth decade of this

century. All the same, it was not the first expression of its kind. A close

look at the literary corpus of the nineteenth century reveals the traces of a

gradual change and its final consolidation with Ghalib. There can be little

doubt that a transformation in the form and purpose of Urdu literature

sets in after the 1857 débâcle, reaching its completion in the works of two

of the most powerful and influential writers of the early twentieth

century, Iqbal and Premchand.

Thus the Progressives of the 1930s were not without predecessors and

mentors. And strangely, both Iqbal and Premchand shared a set of ideological

features—anti-imperialism, anti-feudalism, anti-capitalism, and

socialism verging on social revolution—which they bequeathed to the

Progressives who, by and large, adopted them.

Iqbal and Premchand and their ideological predilections were not the

only influence. The Progressives were affected equally, in a most direct

and profound way, by the rapid growth of socialist and communist political

parties nationwide. It is for this reason that one sees an unmistakable

influence of leftist political parties and their ideals on many of the early

Progressives—especially the Communist Party, which was both exceedingly

well organized and the most powerful of any political bodies in the

country calling for social revolution. This was the party most able to

stimulate and organize the working classes—the peasants, the urban

proletariat, the lower middle-class.

As in other sections of the politically conscious element of the Indian

population, the communists had their allies and followers among the

writers. Many of the leading members of the PWA in 1936 were either

intrepid and ardent communists themselves or, at any rate, “fellowtravelers”

of the communists. And there was a certain doctrinaire layer in

the PM which tried to forge an identity between the principles and

activities of the PWM and the communist movement. Many of the

conflicts—both ideological and organizational—within the PWM were a

consequence of the contradiction between the dogmatists like Sajjad

Zaheer and Ali Sardar Jafari on the one hand and Maulana Hasrat

Mohani, Ismat Chughtai, Saadat Hasan Manto, Akhtar Husain Raipuri,

and Ahmed Ali on the other. They were all Progressives, even organizationally

much of the time, and continued to claim their association

with the movement until the end of their careers, and yet we find them expressing their conflicts quite loudly, sometime even quite violently.

Ahmed Ali’s case represents that of many anti-doctrinaire Progressives

who did not “betray” the Movement, although some of the die-hard

officials of the PWA criticized and even anathematized them. What had

happened was that as time passed the exigencies of the political

movement changed the conflicting principles on both sides and impelled

the various groups and individuals in the overall PM to fall apart, and

rifts and schisms were created.

Ahmed Ali, in the Afterword referred to above, has given expression

to such a schismatic ideological position, in contradiction to the officiallyproclaimed

schismatic ideology. But there is no reason for us to disbelieve

him when he claims that he was among the prime movers of the PM and

had remained a staunch follower of the original principles on which it was

founded.

In his short story “Mera Kamra,” he has given expression to his lifelong

social and political ideals. In the dialogue between Lenin and the

Devil we find Ahmed Ali making Lenin express the following sentiments:“But you are an egoist, my friend. You are bitter against the

design of Nature for not creating a mate for you. We want to

demolish the designs of self-seeking men to perpetuate superstition

and ignorance, and overthrow the yoke of ages, and put an end to

all forms of exploitation, mental or material. We have no sympathy

with Anarchy as you had planned; we stand for Revolution and the

Rights of Man. And whereas it was because of this we shall succeed…” (p. 68)

There is no difference between these principles and the general

principles of the Progressive Movement as envisaged by its founders.

Mevlut Ceylan Interviews

Ahmed Ali (1910-1994)

Karachi: August 1986

Mevlut: When selecting your wording what do you pay most attention to? Does sensitivity or does content play a greater role when you choose your words?

Ahmed: It is the subject that calls up words. Meanings and words are interrelated. Without sensitivity one cannot choose the right word for the right meaning, though in all true art it is the computers of the mind that matches words and meanings. In ordinary language, it is only through symbols that one can suggest the meaning.

The symbols of poetry are words. Words have different qualities, of similes or metaphors, which reach different levels, simile traveling along certain levels, allegory sounding deeper levels through metaphor. All art is creation which springs from the unknown subconscious. It is a complex abstract process which, in order to assume concrete form, employs images which, in poetry, assume the form of words, in painting of colour, and sound in music.

Ideas belong to the realm of thought which is a hidden activity and requires expression to come into the open. But words are not ideas; they are only symbols which have acquired certain definite meanings which are often nebulous. Nevertheless they evoke response similar, or close to, the ideas or feelings of the creator or vates as the poet was called, or as close as the associative quality of words can communicate them to the sensitivity of the reader.

Poetry and prophecy are akin in delving into the source of inspiration (called revelation in the case of poetry); only poetry fails to reach the innermost depth of the dark force that lies hidden in the collective subconscious we call divinity.

Semantic symbols in the form of simile and metaphor play an illuminative role in poetry, and metaphor and allegory in prophecy. In poetry a single word can illumine connections which the multitude cannot grasp; and in allegory the significance is communicated to the select few, though the word is available to all.

A common example from poetry could be:

My love is like a red, red rose

That's newly sprung in June

Robert Burns |

Which would not mean anything to a person who has not seen a rose. For allegory, consider

It is one who conjoined two large bodies of water,

One fresh (and) sweet, the other brine (and) bitter,

And has placed an interstice, a barrier between them

Qur'an, 25:53 |

You can yourself draw the conclusion: which plays a more important role in poetry, content or word or both!

Mevlut: When did you first get involved with poetry?

Ahmed: I suppose when I was eleven or twelve, though even as a child, my mother used to tell me, and I have a vague recollection of it, I used to babble for hours playing by myself, making up words that made no sense.

Mevlut: Do you think that special situations are needed for writing poetry? Does poetry live within you?

Ahmed: Being “wrapt up” in poetry does not make you a poet, as being dressed up in clothes does not make you a man, though it may give you culture and polish. The springs of poetry lie within you; you cannot acquire them by reading which, however, may impart appreciation and a criterion of good and bad, that is, literary efficiency.

Since poetry resides within you, special “situations” are necessary to bring it our of you. The name of “situations” in art and poetry is experience. Feeling and the capacity to experience being inborn, only those can feel and experience who are sensitive by nature.. In fact, predilection to poetry itself occasions situations, as it is visionaries who alone see visions which non-visionaries can neither invent nor see.

Mevlut: Can you comment on the development of literature (in particular of poetry) and the stage, which it has reached today? In today's mass media and era of high technology of communications, do you think that literature has been untouched by these – can mass media convey the messages in poetry or art—changes?

Ahmed: One requisite of poetry is leisure. Without leisure one cannot contemplate. Without contemplation emotion cannot open out into its many-coloured spectrum nor find occasion for recollection in tranquility which renews the springs of inspiration. You cannot write poetry riding a double-decker bus in the madness of London rush.

Few have, therefore, been able to write poetry in our day, except by finding refuge in the isolation of their minds: Ezra Pound in his essentially demented personal situation, T.S, Eliot in the paranoiac awareness of the irreligiosity of his generation and the consequent escape into the psychotic state of Christian mysticism, and Rainer Maria Rilke in the loneliness of suffering and resultant leisure his peculiar circumstances provided for contemplation as the Duino Elegies show. Nonetheless, with the exceptions of Rilke it is doubtful if their poetry achieved real greatness – Pound is so fragmented.

The art of poetry has been progressively declining since its rise in the Elizabethan age, in the same proportion as material success incumbent on imperialist expansion and industrialization, the consequent hurry and mechanization of life have increased, culminating in the increase of materialism represented by Darwin's devastating theory of man's descent from the ape.

This took away the sense of wonder at the phantasmagoria of life and the divine order of Creation, and gave rise to pessimism which has led to the gradual desiccation of whatever hope remained in the eternal mystery of the beginning and the End.

The best ages of poetry in the West, to confine ourselves to the English-speaking world, were the Elizabethan and the Caroline when in the former a new wide vista of hope and wonder was opening up before the mind, and in the latter a leisure was created for contemplation and love after the turmoil in the intervening decades. (See, for instance, Andrew Marvell's “To His Coy Mostress.”) The French Revolution broke the atmosphere of complacency that had come upon Europe, and agitated the spirit into a second Romantic interlude.

But it was short-lived and marked with a sense of haste, as though a hidden hand were pushing it out. And the poetic careers of Wordsworth and Coleridge were confined to the brief period of the Lyrical ballads, and those of Shelley, Keats and Byron were too short.

The coming Industrial Revolution, trailing into the Victorian age, produced an era of skepticism, doubt, and a false sense of security in imperialism and the certainty of possessing everything that was good and beautiful, and the hypocrisy of Victorian morals against the background of prostitution and French cancan . . . The poet of fin de siecle is consequently sick and tired, and easily trails off into the sentimentality of the Georgians when the poets were crying over the dead ass as if it were their brother.

Today, with all sense of wonder drained by the arrogance of power, the nuclear explosions, the conquest of space, Reagan's Star Wars, there is no room for wonder or poetry. Man has become his own creator and destroyer; the Big Idea of life has fled. When all real poetry and literature, the greatness of thought and the written word have been drowned in the noise of electronic machines, the tape and the TV, the radio, the screen, and the computer has replaced the human mind, what message there then remains for man's artificial devices to convey, when the spirit itself is dead?

Mevlut: Do you think that poetry can change our world? Why poetry?

Ahmed: In view of what has been said above, which seems to point to the death of poetry, how can it “change the world”? Not that poetry does not have the power to change the world. It has definitely changed it once. That was after the invasions of Changez Khan and Halaku's hordes when the Islamic world lay devastated in the throes of death with no hope of its rising out of the traumatic experience.

What then sustained the Muslims and raised them out of their stupor was the poetry and message of Jaluddin Rumi and Sa'di Shirazi which filled them with hope and vigour again. There was no other power that could have awakened them and made them whole. But then belief was alive; today faith in the eternal principle and the guiding hand that shapes the destiny of man is dead.

Mevlut: How do you relate the essence of the poem with its style?

Ahmed: The answer to the relation of the essence of the poem with the style lies embedded in the answer to questions above. It is essentially the nature of the subject that dictates the style, the subconscious acting as computer.

Mevlut: In your view, what makes a poem relevant for the future?

Ahmed: The factor that contributes most to the relevancy of a poem is the nature of experience. If it has a lasting import and universality, it cannot fail to cast its shadows into the future. Its relevancy to the future lies in its presenting the eternal verities of life, of fellow-feeling and bearing with fortitude the trials that befall. Its appeal even to the future is assured in such a case.

posted 8 July 2005

| Ahmed Ali (1910-1994)

Man of Letters , short story writer, literary/cultural activist, novelist, translator, diplomat, university professor, poet was born in Delhi in 1910, and educated at Aligarh and Lucknow universities: B.A. (Honours), 1930 and M.A. English, 1931. H is circle of friends included E. M. Forster, George Orwell, Virginia Wolf and the Bloomsbury Group, Han Su Yin, Tien Chen, Sarojini Naidu, Laxmi Pandit, Raja Rao, Jamni Roy,Kunwar Natwar Singh and the Surahwardy family; Mohsin Abdullah and Laurence Brander from Aligarh and Lucknow |

were his dear friends to the end. Ahmed Ali died in Karachi on 14th January 1994.

During a period in which a modernist movement in Urdu literature, Ahmed Ali co-authored the historic and revolutionary collection of Urdu short stories Angaray [ Red Hot Coals]. Angaray criticized mullahs, social hypocrisy and much else, caused an uproar. The authors were accused of being “atheists” and “anti-Muslim.” The Government of India banned the book.

On April 5, 1933 Ahmed Ali and Mahmuduzzafar published a joint statement “In Defence of Angaray ” in The Leader , [Allahbad] and proposed a League of Progressive Authors, which would bring out similar collections. In 1936 this became “The All India Progressive Writers Association" committed to independence, religious harmony and the socialist, egalitarian creed..

Ahmed Ali broke away from the Progressive Writers Association, amid much acrimony and accusations of betrayal he could not accept limitations imposed by the Marxist ethos and wanted to explore dimensions beyond proletariat literature and went to on found, The Progressive Writers Association which was to have far-reaching consequences for South Asian literature.

In 1934, he published his first Urdu collection ' Shole y [ Flames ].His much-praised Urdu short story 'Hamari Gali' set in Delhi was published in New Writing in London. 'Hamari Gali' took him back to his roots, to Delhi and made him realize that he wanted a much larger canvas to portray its bygone culture.

To reach a broader anglophone audience Ali wrote Twilight in Delhi in English, first published by The Hogarth Press in London in 1940 . The novel provides a portrait of the static and decaying traditional culture of Delhi, the Mughal capital, while the British hold the Coronation Durbar of 1911 and draw up plans for their new imperial city, New Delhi.

Here's a poetic passage from Twilight in Delhi:

Night envelopes the city, covering it like a blanket. In the dim starlight roofs and houses and by-lanes lie asleep, wrapped in a restless slumber, breathing heavily as the heat becomes oppressive or shoots through the body like pain. In the courtyards, on the roofs, in the by-lanes, on the road, men sleep on bare bed, half naked, tired after the sore day's labour. A few still walk on the otherwise deserted roads, hand in hand, talking; and some have jasmine garlands in their hands. The smell from the flowers escapes, scents a few yards of air around them and dies smothered by the heat. Dogs go about sniffing the gutters in search of offal |

His linguistic strategy was innovative and courageous, a hallmark in efforts to translate one culture (Urdu and Persian images; traditional Indo-Muslim culture ) into the language of another culture, a colonial and imperial power, namely, English.

Ahmed Ali's other works include two novels, Ocean of Night and Of Rats and Diplomats ; The Prison-House ; Purple Gold Mountain ; Selected Poems ; Mr. Eliot's Penny-world of Dreams ; Muslim China ; Ghalib: Selected Poems, The Problem of Style and Technique in Ghalib ; and The Flaming Earth .

Professor Ahmed Ali translated from Urdu, Persian, Indonesian, Chinese and Arabic. His translation of classical Urdu poetry, The Golden Tradition (Columbia University Press, 1973), makes an important contribution to the study of comparative literatures, and surveys in depth the literary and philosophical background of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries.

AI-Qur'an, A Contemporary Translation (Princeton University Press, Oxford University Press & Akrash) is Professor Ahmed Ali's most outstanding contribution in the field of translation. Approved by eminent Islamic scholars, it has come to be recognised as the best of existing translations of the holy Qur'an.

Professor Ahmed Ali was a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Humanities at Michigan State University in 1975, Fulbright Visiting Professor of History at Western Kentucy University and Fulbright Visiting Professor of English at Southern Illinois University in 1978-79. He was made an Honorary Citizen by the State of Nebraska in 1979. He was Visiting Professor at the University of Karachi during 1977-79, which later conferred on him an honorary degree of Doctor of Literature in 1993.

A distinguished gentleman of refined taste and manners, Professor Ahmed Ali had a deep interest in sufism and a passion for Ghalib. His writings voiced concern over the decay of Muslim culture and the injustices of colonial powers. |

posted 8 July 2005

Professor Ahmed Ali was responsible for writing arguably the greatest novel ever written about Delhi. Born in Delhi, India, he was involved in progressive literary movements as a young man. He contributed to Aangarey ( Red Hot Embers, 1933 ), a collection of short

Professor Ahmed Ali was responsible for writing arguably the greatest novel ever written about Delhi. Born in Delhi, India, he was involved in progressive literary movements as a young man. He contributed to Aangarey ( Red Hot Embers, 1933 ), a collection of short  stories that caused an uproar among fundamentalist Muslims. The book was banned in March 1933, the publisher was raided by police, and copies of the book were burnt in the streets. His other books include: The Golden Tradition (translations of Urdu poetry); Ocean of Night ; Of Rats and Diplomats ; Twilight in Delhi ; and Al-Qur'an, a Contemporary Translation .

stories that caused an uproar among fundamentalist Muslims. The book was banned in March 1933, the publisher was raided by police, and copies of the book were burnt in the streets. His other books include: The Golden Tradition (translations of Urdu poetry); Ocean of Night ; Of Rats and Diplomats ; Twilight in Delhi ; and Al-Qur'an, a Contemporary Translation .

Mahmud-uz-Zaffar announced the formation of a "League of Progressive Authors", which was later to expand and become the All-India Progressive Writers' Association. Ahmed Ali presented his paper Art ka Taraqqi-Pasand Nazariya in its lnaugural Conference in 1936. A pioneer of the modem Urdu short story, Ahmed Ali's works include collections of short stories: Sholay (1934); Hamari Gali (1940); Qaid Khana (1942); and Maut Se Pahle (1945).

Mahmud-uz-Zaffar announced the formation of a "League of Progressive Authors", which was later to expand and become the All-India Progressive Writers' Association. Ahmed Ali presented his paper Art ka Taraqqi-Pasand Nazariya in its lnaugural Conference in 1936. A pioneer of the modem Urdu short story, Ahmed Ali's works include collections of short stories: Sholay (1934); Hamari Gali (1940); Qaid Khana (1942); and Maut Se Pahle (1945).  have been written in English while those who had read it in the original English said it was untranslatable. This curious controversy was put to an end by the American critic, Dr. David D. Anderson, when he said: "the novel transcends language as any substantial work of art ultimately must do…".

have been written in English while those who had read it in the original English said it was untranslatable. This curious controversy was put to an end by the American critic, Dr. David D. Anderson, when he said: "the novel transcends language as any substantial work of art ultimately must do…".