| ||||||

| Articles | Projects | Resume | Cartoons | Windsurfing | Paintings | Album |

More Whale Blubber? Yes, Thank You!

The Benefits and the Dangers of the Country Food Diet of the Inuit People of Northern Canada

by Waterose

for more Cartoons

�����The Canadian North means different things to different people. To some people it is a cold, distant, foreign place, but to other people it is a special place that is home. A homeland should provide security and resources for prosperity and growth of future generations of the people.

�����The people of the North are the Inuit and their future existence is threatened by the toxic poisons in their homeland and in their traditional natural foods which are called "country food"(Wenzel 118). Country food is all harvested wildlife and is comprised primarily of seal, whale, caribou and fish (ibid 130). The Inuit can consume either toxic country food or expensive imported food. Neither choice offers optimal health benefits. However, the best choice for the survival of the Inuit is to cultivate their experience and knowledge in wildlife harvesting to obtain country food. This is the best choice because of the physiographic nature of the region, the natural resources available to the people, the causes of the toxicity, and most importantly, the global recognition and participation in the solution to the problems faced by people in the North.

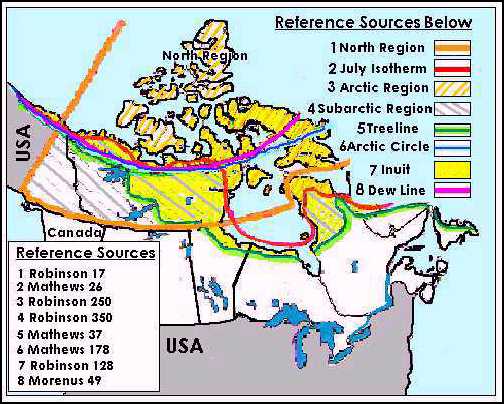

�����For the purpose of further discussion certain terms need to be defined regarding location, place, and the people. Attached is Appendix I Map: The Canadian North Defined which illustrates points of discussion for reference purposes. The North region in Canada is "defined by political criteria ... as [the] Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories, north of 60 degrees North latitude" (Robinson 19). This region can be divided into two sub-regions, the Arctic and the Subarctic, on the basis of climate (ibid 250). The line of demarcation is the 10�C isotherm for July which does not follow the Arctic Circle defined by the 66.5 degrees North latitude (ibid). The Arctic is located north of the 10�C July isotherm, and the Subarctic is located south of the 10�C July isotherm (ibid). The North region is comprised of a wide range of landforms which includes: from the west to the east, the Northern Cordillera of B.C. mountains, the Mackenzie Valley Interior Plains, the Canadian Shield and Precambrian rock, and the Arctic Islands (ibid 251).

������This region is characterised by a cold climate and a sparse population density. The average winter temperatures are cold ranging from -30�C to -20�C (Mathews 25) and the average summer temperatures are cool ranging from 10�C to 20�C (ibid), depending on latitude and proximity to moderating water bodies. The average annual precipitation is low ranging from 0-80 cm (ibid), with "12-15 cm in North Central Canada and desert conditions in the central Arctic" (Robinson 29). Due to this harsh climate, this region cannot support agriculture and the people rely on hunting as the primary source of country food (ibid 254).

������The people of the North include non-indigenous people, the Inuit people and the Indian people (Robinson 258). The Inuit live North and east of the tree line (ibid). This area is located on Appendix I Map. The Indians live south of the treeline (ibid). "The Inuit are the chief inhabitants of the treeless Arctic region, whereas Indians are a minority group in the forested Subarctic Northwest region" (ibid). The Inuit live in a region which has a very limited carrying capacity for population because of the physiography and climate.

������The population density in the North is sparse. The Yukon Territory has a gross population of 27,797 persons with a population density of 0.06 persons per square kilometre (Mathews 7). The Northwest Territories has a gross population of 57,649 persons with a population density of 0.02 persons per square kilometre (ibid). The low population density is directly related to the natural resources provided by the region. The climate of this region is too inhospitable to be attractive to non-indigenous people, hence the indigenous people comprise the majority of the population in the North region. The harsh climate conditions render transportation over vast distances practically impossible, and expensive by traditional southern standards. This expensive cost of transportation inflates the cost of imported food products from the south to the North (Wenzel 118-119).

������The nutritional value of southern convenience foods is insufficient to meet the caloric needs of the Inuit (Native Foods 35, McCarten). " 'In cold temperatures, people tend to need more calories to fend off the cold, a lot more than people in the south are likely to need', said Dr. Bev Hasten of the Health Protection Branch in Ottawa" (McCarten). However, Nutrition Canada reports in an earlier study in 1975 that the Inuit consistently have lower median caloric intakes than the national median caloric intakes (Eskimo Survey 33). The lower caloric intake may be due to the consumption of imported southern foods rather than country food. The nutritional value in country food can sustain the Inuit dietary needs. It is important to note that the Inuit obtain essential natural oils from animal fats that non-arctic populations obtain from vegetable oils. The country food diet is essential to the Inuit way of life. The physiographic and climatic characteristics of the North determine the types of natural resources available to the Inuit and to the animals they harvest for food.

������The problems associated with harvesting and consuming country food are multitudinous. Country food contains poisonous toxins. The scientific factors of the long term effects of the toxins are uncertain, the climate of the region retards decomposition of the toxins, the local and multi-national points of origin sources complicate safe control of the toxins, and global forces move anthropogenic toxins in the hydrologic cycle.

������Scientific and technological anthropogenic contributions to the North significantly alter the environment. The effects of the introduction of synthetic chemicals into the environment are only being discovered and analysed in recent years. Two key characteristics of the North are the cold temperatures and the low amounts of precipitation that hinder the decomposition of synthesised compounds. Thus, the toxic compounds are stable longer and in relatively higher concentrations in the ecosystem. The ecosystem includes the abiotic and the biotic elements.

������The biotic consumers ingest the toxins beginning with the oceanic plankton (Twitchell 54). The concentration of toxic substances in animal tissues increases exponentially with each shift in the food chain by means of biomagnification (ibid). Evidence of toxicity in the food chain in the North includes the following: "dangerously high levels of cadium and mercury ... in the meats and fats of ringed seals and beluga whales" (McCarten), "polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB's) in polar bears in concentrations three billion times greater than in the Arctic Ocean" (Twitchell 54), "organochlorines [that] accumulate in the fat of whales, seals, and caribou" (ibid 55), and "toxaphenes in arctic whales and fish" (ibid 57). The absolute and long term effects of these toxins in the Inuit diet is uncertain. However, it is certain that the "most severe damage occurs [in the foetus] before birth" (Cone) and that "Inuit women have six times more PCB's in their milk than women in the south" (ibid). The presence of these and other toxins lowers the immune system and "Inuit infants have provided a living test tube for immunologists" (ibid). "There is a marked increase in the incidence of infectious disease among breast-fed babies exposed to a high concentration of contaminants" (ibid). There is a much higher disease rate in the North than in the south including "meningitis, bronchitis, pneumonia" (ibid), "diabetes and cardiovascular disease" (Native Foods 36-37). This is strong evidence to suggest an unhealthy connection between toxic contaminants in the North and the country food diet of the Inuit people.

������The source of the contaminants in the North is nebulous. Each type of source requires a different type of solution. There are primarily three types of point of origin sources ranging from local to global; these include leakage from dump sites, individual spill sites, DEW Line stations (Distant Early Warning Line system), and trans-boundary global pollution. Concerning localised problems, the Inuit people can learn from mistakes made in the south and initiate stringent waste management plans. "Poison in the Land" describes a typical example of a localised problem (Poison 7). The Apex dump, located near Iqualuit (62�N 62�W) [see Appendix 1 Map for location], leaches "poisonous metals...into the soil, drinking water...and the clam digging areas" (ibid). "The federal government ... [will pay] $2 million to remove contaminated soils and to tear down a building floor that is covered with PCB-laden transformer oil ... and another $150,000 to pay the cost of crushing barrels at the North 40 dump site" (ibid). Localised problems are expensive to clean up, but they can be accomplished.

������Periodically, a localised spill can cause a catastrophic event. The Exxon Valdez event of March 24, 1989 is the largest oil spill in the Arctic region - "over eleven million gallons of crude oil spread over 1,000 square miles of water and land (500 miles of shoreline)" (Oil Age 312). This oil spill devastated marine mammal resources and fish stocks that the Inuit rely on for country food (ibid). The technology used for cleaning up this oil spill exacerbated the problem by forcing the oil on the shoreline back into the ocean and "killing all surface and subsurface animal and plant life to seven inches below the surface" (ibid 2). The Arctic is frequented by ocean tanker vessels carrying oil and there have been many frequent smaller oil spills (ibid 312). However, this catastrophic event triggered global awareness to the dangers of oil freighter traffic in the Arctic and forced industry and governments to initiate emergency contingency plans in the event of a similar future occurrence. Clean up technology and emergency clean up action plans for oil spills are now in place globally, and in Canada (Burrard Clean).

������The issue cleaning up the old DEW Line stations represents a unique problem for discussion because the solution involves co-operation between United States (USA) and Canada. The DEW Line stations were constructed by USA and Canada in the Arctic from Alaska to Eastern Canada during the period of 1952 to 1957 (Morenus front flap) at a cost of more than $700,000,000 to Canada and USA (ibid 175). The DEW Line consisted of three thousand miles of towers, stations, and lines that functioned as a radar detection system in case North American air was invaded by hostile forces (ibid 159). The purpose of the DEW Line became obsolete with satellite technology and the equipment at the DEW Line sites has been abandoned. The sites leak deadly levels of PCB toxins. The most interesting aspect regarding the clean-up of the DEW Line sites is the provision of the Nunavut settlement agreement between the Inuit and the government of Canada. More specifically, Article 11, Part 9, Section 11.9.1 provides for special treatment regarding prioritising waste clean-up of the abandoned Dew Line sites (Agreement 99). This section recognises the severity of the problem and provides a mechanism for solution. Furthermore, the Inuit authorities insist that the Department of National Defence provide in-depth and conclusive proof that the plans for clean-up provide a viable solution under Arctic conditions (National 1-2). This demand reflects the growing concern and wisdom of the Inuit in that they are taking more responsibility for the health and welfare of their land. It is ironic that Morenus describes the Dew Line in terms of "The Dew Line may well be our lifeline!" (Morenus 183) when in fact the Dew Line is the most significant contributor of PCB's in the North. The Dew Line is a trans-border problem involving only two countries and requires co-operation between Canada and USA for resolution of the problem.

������Canada and United States are working together towards solutions. They participated at a special multi-national conference, "The Arctic: Choices for Peace and Security - A Public Inquiry, held March 18 and 19, 1989 in Edmonton, Alberta" (Arctic 5). The issues included "Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic, ... resource extraction, ... and the preservation of the Arctic" (ibid 9). Mary Collins, Canada's Associate Minister of National Defence, delivered the opening remarks speech calling for mutual international co-operation for "environmental integrity" (ibid 18) of the North. John F. Merritt, executive director of the Canadian Arctic Resources Committee, presented an overview of the environmental problems plaguing the North and summarised the international problem of pollution drifting in the oceans and atmospheric cycles.

������"It is even more important to tackle the larger problems causing deteriorating global air quality and the poisoning of the planet's oceans. It will take concerted international action, based on a recognition that pollution is no respecter of sovereignty, to deal with these issues. It is only international co-operation, which Canadians should pursue both as individuals and as a people, that will prevent the Arctic Basin sink from becoming the Arctic Basin cesspool" (Arctic 26).

������While this conference did not in itself produce significant results, it did set a precedent for significant future international negotiations towards solutions.

������Subsequent to this conference, other international conferences focusing on the "importance of Arctic Ecosystems and an increasing knowledge of global pollution and resulting threats to the environment and to the people that depend on country foods in the Arctic and Subarctic"(Kakfwi) followed. These conferences include: the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy in 1989, the First Ministerial Conference in Finland-1991, and the Second Conference of the Ministers in Greenland-1993 at which the Ministers signed a Declaration on Environment and Development in the Arctic (Kakfwi). In Canada, a special three year study was initiated in 1994, the Eco-Research project on Contaminants in the Eastern Canadian Arctic, to "gain an understanding of the effect of food chain contaminants of the health and quality of life of the Inuit People" (Risk 6). This project includes workshops between the Inuit, the government, the academic researchers, and the industrial sector to develop strategies for "managing risks imposed by ecosystem contaminants" (ibid). National and international efforts to protect the Arctic environment are reaching a new pinnacle of success in the formation of the Arctic Council this year. The Arctic Environment Ministers signed the:

������"Inuvik Declaration on Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development that includes the full commitment of all eight Arctic countries to establishing an Arctic Council as early as the summer of 1996. The Arctic council will be a forum for international co-operation in environmental, economic, cultural and social concerns of Northerners" (Kakfwi).

������To date, this international effort to protect the Arctic environment is the most significant achievement with respect to alleviating the continued dumping of toxic contaminants into the North region.

������The presence of toxic contaminants in the country food of the Inuit presents a dilemma. Should the Inuit be encouraged to continue to harvest and consume toxic country food at the risk of damaging future generations or should the Inuit be encouraged to abandon traditional country food and consume inappropriate foods imported from the south? The Inuit should cultivate and renew their commitment to harvesting country food because country food can meet their unique food requirements in a cold North region where their caloric needs are higher due to the extended periods of cold climate. Traditionally, the Inuit have harvested wildlife for their food-source, and they have the experience and knowledge in their culture to continue to harvest the natural resources provided by the region. The presence of dangerous toxins in the country food is under extensive investigation by the Inuit, the Canadian government, and the other Arctic countries. Significant steps are being taken, from a local level to the global level, to clean-up existing sites of contamination, and to prevent further exacerbation of additional toxic pollutants from entering the already stressed ecosystem on a global level.

������The Inuit are a small isolated and sparsely populated people with limited economic and political power, yet they are achieving global co-operation and commitment to protect their home, their homeland, their security, their resources, their survival of their future generations and their way of life.

Appendix I: Map

The Canadian North Defined

Works Cited

- Note: Some of the reference links below are no longer valid.

Agreement Between the Inuit of the Nunavut Settlement Area and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. Ministry of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Ottawa,1993.

Burrard Clean Operations, a Division of Western Canada Marine Response Corporation. Colin Hendry. Guest Speaker. Environmental Studies Program. Langara College. October 11,1995.

Cone, Marla."Human Immune Systems May be Pollution Victims." Los Angeles Times. 13 May 1996. Was available at: Oak Internet. On-line. 31 Oct 1996. URL: http://www.math.ucla.edu/~kostello/soc18/articles/immune.htr

Jorgensen, Joseph G. Oil Age Eskimos. Berkeley Los Angeles: University of California Press,1990.

Kakfwi, Stephen. "Ministers Statements to the Legislative Assembly" Office of the Press Secretary. 26 Mar 1996. Was available at: Oak Internet. On-line. 31 Oct 1996. URL:http://www.ssimicro.com/~xpsogn/Net/Text/pr95/statements/arcticenviron.htr

Manitoba Geographical Studies 1. Developing the Subarctic. Ed.John Rogge. Winnipeg:University of Manitoba,1973.

Mathews, Geoffrey J. Canada and the World:An Atlas Resource. 2nd ed. Scarborough:Prentice Hall,1995.

McCarten, James. "Toxic or not, Inuit Stand by Whale Meat". Edmonton Journal. Dec.28 1995. Was available at: Oak Internet. On-line. 31 Oct 1996. URL: http://www.highnorth.no/to-or-n.ht

Morenus, Richard.DEW Line:Distant Early Warning The Miracle of America's First Line of Defense. New York:Rand McNally,1957.

"National Defence asked to Suspend DEW Line Cleanup." Nunatsiaq News. Year 23. Number 16. 19 May 1995.

Native Foods and Nutrition. Minister of National Health and Welfare. Canada, 1985.

Nutrition Canada: The Eskimo Survey Report. Minister of National Health and Welfare. Canada,1975.

"Poison in the Land." Nunatsiaq News 19 May 1995. Year 23 No 16. 7.

"Risk Management Workshops on Ecosystem Contamination in Nunavik and Labrador:The Eco-Research Project." Oak Internet. On-line. 31 Oct 1996.URL: http://sail.uwaterloo.ca/~irr/news.dec95.html#arct

Robinson, J. Lewis. Concepts and Themes in the Regional Geography of Canada. Vancouver:Talonbooks,1989.

True North Strong and Free Inquiry Society. The Arctic:Choices for Peace and Security:A Public Inquiry. Conference Report of Speakers. West Vancouver:Gordon Soules Books,1989.

Twitchel,Karen. "The Not-so-pristine Arctic." Canadian Geographic. Feb/March 91.

Wenzel, George. Animal Rights-Human Rights. Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. Toronto:University of Toronto Press,1991.

email Waterose

email Waterose

Please Sign My Guestbook

Please View My Guestbook

| Articles | Projects | Resume | Cartoons | Windsurfing | Paintings | Album |

| ||||||