Wellington, Oct 4 - The rare Hector's dolphin will probably

disappear from the North Island coastline within a few generations,

scientists predict.

Research publicised today by Green Party co-leader Jeanette

Fitzsimons suggests the dolphin, which is unique to New Zealand and

considered the world's rarest marine dolphin, may soon be confined

to the South Island only.

Currently, up to 120 Hector's dolphins are thought to live off the

North Island's west coast from Kawhia to the Kaipara Harbour.

Up to 4000 live off the South Island, with the biggest population

based near Banks Peninsula.

Wellington, Oct 4 - The rare Hector's dolphin will probably

disappear from the North Island coastline within a few generations,

scientists predict.

Research publicised today by Green Party co-leader Jeanette

Fitzsimons suggests the dolphin, which is unique to New Zealand and

considered the world's rarest marine dolphin, may soon be confined

to the South Island only.

Currently, up to 120 Hector's dolphins are thought to live off the

North Island's west coast from Kawhia to the Kaipara Harbour.

Up to 4000 live off the South Island, with the biggest population

based near Banks Peninsula.

Commercial fishing, particularly through the use of gillnets, has

contributed to their declining numbers.

Ms Fitzsimons said more research into the North Island Hector's

dolphin population was needed urgently.

``We desperately need more research to tell us exactly where the

North Island dolphins are, how many there are and what's killing

them,'' Ms Fitzsimons said.

``In the meantime we need a Hector's dolphin sanctuary

controlling gillnetting and trawling from Kawhia to the mouth of the

Kaipara Harbour.''

Auckland University senior lecturer Scott Baker, who supervised

the research done by doctorate candidate Franz Pichler, said figures

for the North Island Hector's dolphin population were

an estimate only, because there had been so little research.

He said the dolphin would probably be extinct on the North Island

within 10 generations if nothing was done to reverse the trend of

declining numbers.

Commercial fishing, particularly through the use of gillnets, has

contributed to their declining numbers.

Ms Fitzsimons said more research into the North Island Hector's

dolphin population was needed urgently.

``We desperately need more research to tell us exactly where the

North Island dolphins are, how many there are and what's killing

them,'' Ms Fitzsimons said.

``In the meantime we need a Hector's dolphin sanctuary

controlling gillnetting and trawling from Kawhia to the mouth of the

Kaipara Harbour.''

Auckland University senior lecturer Scott Baker, who supervised

the research done by doctorate candidate Franz Pichler, said figures

for the North Island Hector's dolphin population were

an estimate only, because there had been so little research.

He said the dolphin would probably be extinct on the North Island

within 10 generations if nothing was done to reverse the trend of

declining numbers.

Dr Baker said the research by Mr Pichler suggested the North and

South Island reproduced only among themselves.

``What Franz has established is that the North Island population

is distinct genetically from the South Island.''

That meant it was unlikely North Island numbers would be restored

by migration from other areas since the research suggested little or

no breeding between dolphins from different parts of the country.

``If they disappear from the area here they simply would not

return and that's our primary criteria for their importance.

Dr Baker said the research by Mr Pichler suggested the North and

South Island reproduced only among themselves.

``What Franz has established is that the North Island population

is distinct genetically from the South Island.''

That meant it was unlikely North Island numbers would be restored

by migration from other areas since the research suggested little or

no breeding between dolphins from different parts of the country.

``If they disappear from the area here they simply would not

return and that's our primary criteria for their importance.

``The historical evidence tells us they're simply not moving

between the areas and they're not reproducing, they're not

interchanging genes and they're not moving physically.

``Based on that historical evidence

-- that is, we assume that's been the case over the past hundreds,

thousands of years -- if this little group goes extinct they just

won't come back.''

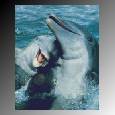

Dr Baker said the North Island dolphins had different markings,

and were larger, than the South Island population and there had been

speculation over many years that they were a different species or

subspecies to the South Island dolphin.

``The historical evidence tells us they're simply not moving

between the areas and they're not reproducing, they're not

interchanging genes and they're not moving physically.

``Based on that historical evidence

-- that is, we assume that's been the case over the past hundreds,

thousands of years -- if this little group goes extinct they just

won't come back.''

Dr Baker said the North Island dolphins had different markings,

and were larger, than the South Island population and there had been

speculation over many years that they were a different species or

subspecies to the South Island dolphin.

Evidence from Hector's dolphin deaths off the North Island

coast, suggested their numbers may already have deteriorated to the

point where problems related to a dying species, such as inbreeding,

were beginning to occur.

``In recent years animals that have washed up dead on the

beaches, of the five or six I can think of

... several of them have been adult females with young calves and

that is a little bit troubling because that's not common in the

South Island.

Evidence from Hector's dolphin deaths off the North Island

coast, suggested their numbers may already have deteriorated to the

point where problems related to a dying species, such as inbreeding,

were beginning to occur.

``In recent years animals that have washed up dead on the

beaches, of the five or six I can think of

... several of them have been adult females with young calves and

that is a little bit troubling because that's not common in the

South Island.

``That would be consistent with an inbreeding effect; that

animals are having difficulty with birth or neonatal mortality and

that sometimes carries the adult along with them.

``But we can't say with much certainty -- when you get a

population this small generalisations are hard.''

Dr Baker said more research was needed to discover why the

dolphins were dying but it wasn't always easy to get funding.

The first stage of the university's work was funded by grants

from the Worldwide Fund For Nature and the Department of

Conservation.

The next stage of the research would be to collect DNA samples

from North Island dolphins in an information-gathering exercise,

which would also allow their population to be tracked over time, Dr

Baker said.

``That would be consistent with an inbreeding effect; that

animals are having difficulty with birth or neonatal mortality and

that sometimes carries the adult along with them.

``But we can't say with much certainty -- when you get a

population this small generalisations are hard.''

Dr Baker said more research was needed to discover why the

dolphins were dying but it wasn't always easy to get funding.

The first stage of the university's work was funded by grants

from the Worldwide Fund For Nature and the Department of

Conservation.

The next stage of the research would be to collect DNA samples

from North Island dolphins in an information-gathering exercise,

which would also allow their population to be tracked over time, Dr

Baker said.

But the university was yet to hear back from the WFN and DOC over

a proposal for funding it put up in March.

The Public Good Science Fund had responded to funding requests in

the past with the response that any such funding had to come from

DOC.

``So work that we consider fundamental science on biodiversity

and the environment and endangered species, they (the Public Good

Science Fund) view as a DOC management issue.

``We don't seem to be easily eligible for that kind of thing and

I think that's a flaw in the system because DOC has got huge

responsibilities and very limited funding.''

Ms Fitzsimons said DOC didn't have enough money to do its job.

``The little money DOC has for the Hector's dolphin has gone to

sustaining the South Island subspecies.''

The North Island researchers have been able to continue only

thanks to private organisations like the Worldwide Fund for Nature

and have even forced to fund some research out of their own

pockets.''

The Green Party today released its conservation policy, with a

North Island sanctuary among its measure

But the university was yet to hear back from the WFN and DOC over

a proposal for funding it put up in March.

The Public Good Science Fund had responded to funding requests in

the past with the response that any such funding had to come from

DOC.

``So work that we consider fundamental science on biodiversity

and the environment and endangered species, they (the Public Good

Science Fund) view as a DOC management issue.

``We don't seem to be easily eligible for that kind of thing and

I think that's a flaw in the system because DOC has got huge

responsibilities and very limited funding.''

Ms Fitzsimons said DOC didn't have enough money to do its job.

``The little money DOC has for the Hector's dolphin has gone to

sustaining the South Island subspecies.''

The North Island researchers have been able to continue only

thanks to private organisations like the Worldwide Fund for Nature

and have even forced to fund some research out of their own

pockets.''

The Green Party today released its conservation policy, with a

North Island sanctuary among its measure

The fishermen of Futo, Japan, brought in a profitable catch last week: dozens of dolphins herded into a circle of nets and driven toward shore.

The sea runs red with dolphin blood after the massacre.

The fishermen of Futo, Japan, brought in a profitable catch last week: dozens of dolphins herded into a circle of nets and driven toward shore.

The sea runs red with dolphin blood after the massacre.

Most of the captured animals are about to meet a brutal and heartbreaking end. But a few of the best are worth as much as $30,000 to meet a growing international demand for captive dolphins.

Most of the captured animals are about to meet a brutal and heartbreaking end. But a few of the best are worth as much as $30,000 to meet a growing international demand for captive dolphins.

At a marine park near Tokyo, the dolphins put on the kind of show that is now a staple of aquariums and amusement parks around the world. But that's not the whole story.

For those dolphins left behind last Thursday the killing was about to begin.

Those dolphins not young enough or attractive enough for marine parks were about to be turned into meat and fertilizer. Some trucked away were still alive.

At a marine park near Tokyo, the dolphins put on the kind of show that is now a staple of aquariums and amusement parks around the world. But that's not the whole story.

For those dolphins left behind last Thursday the killing was about to begin.

Those dolphins not young enough or attractive enough for marine parks were about to be turned into meat and fertilizer. Some trucked away were still alive.

"It's an unbelievable act of cruelty to an animal that I really love," says Hardy Jones, a documentary film maker, who has photographed the same kind of capture as that occurring last week.

"And to watch it happen the only thing I can do is say to myself, 'Take the pictures and get them out so the world can see,'" he says.

If the world is outraged, it's because so many have come to know dolphins so well in captivity at parks like Sea World in San Diego.

"People can come here and learn about dolphins, experience them first hand, interact with them personally," says Jim Antrim of Sea World. "I think that's leading to a better level of understanding and appreciation for them."

American law forbids importing wild dolphins. Those at Sea World were bred in captivity. But continuing international demand is still leading to the slaughter of animals known as gentle, intelligent and friendly.

"It's an unbelievable act of cruelty to an animal that I really love," says Hardy Jones, a documentary film maker, who has photographed the same kind of capture as that occurring last week.

"And to watch it happen the only thing I can do is say to myself, 'Take the pictures and get them out so the world can see,'" he says.

If the world is outraged, it's because so many have come to know dolphins so well in captivity at parks like Sea World in San Diego.

"People can come here and learn about dolphins, experience them first hand, interact with them personally," says Jim Antrim of Sea World. "I think that's leading to a better level of understanding and appreciation for them."

American law forbids importing wild dolphins. Those at Sea World were bred in captivity. But continuing international demand is still leading to the slaughter of animals known as gentle, intelligent and friendly.

�1999, CBS Worldwide Inc., All Rights Reserved.

�1999, CBS Worldwide Inc., All Rights Reserved.

Dolphin Decision. On Apr. 29, 1999, Secretary of Commerce William Daley

issued a rule that would allow fishermen who use of tuna seines to

surround dolphins in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to be labeled such

tuna as "dolphin-safe" as long as no dolphins are observed to be killed or

seriously injured. This decision was taken after U.S. managers determined

that there was insufficient evidence that such fishing had a significant

adverse effect on dolphin populations. [American Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty of Animals press release, Assoc Press, NOAA press

release]

Dolphin Decision. On Apr. 29, 1999, Secretary of Commerce William Daley

issued a rule that would allow fishermen who use of tuna seines to

surround dolphins in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to be labeled such

tuna as "dolphin-safe" as long as no dolphins are observed to be killed or

seriously injured. This decision was taken after U.S. managers determined

that there was insufficient evidence that such fishing had a significant

adverse effect on dolphin populations. [American Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty of Animals press release, Assoc Press, NOAA press

release]

Double click on picture in cube to go to:Seashepherd org,Friends of the Ocean,D.E.E.P Online,Cetacean Society International,Save the dolphin,Pam for the love of dolphins

Double click on picture in cube to go to:Seashepherd org,Friends of the Ocean,D.E.E.P Online,Cetacean Society International,Save the dolphin,Pam for the love of dolphins

Wellington, Oct 4 - The rare Hector's dolphin will probably

disappear from the North Island coastline within a few generations,

scientists predict.

Research publicised today by Green Party co-leader Jeanette

Fitzsimons suggests the dolphin, which is unique to New Zealand and

considered the world's rarest marine dolphin, may soon be confined

to the South Island only.

Currently, up to 120 Hector's dolphins are thought to live off the

North Island's west coast from Kawhia to the Kaipara Harbour.

Up to 4000 live off the South Island, with the biggest population

based near Banks Peninsula.

Wellington, Oct 4 - The rare Hector's dolphin will probably

disappear from the North Island coastline within a few generations,

scientists predict.

Research publicised today by Green Party co-leader Jeanette

Fitzsimons suggests the dolphin, which is unique to New Zealand and

considered the world's rarest marine dolphin, may soon be confined

to the South Island only.

Currently, up to 120 Hector's dolphins are thought to live off the

North Island's west coast from Kawhia to the Kaipara Harbour.

Up to 4000 live off the South Island, with the biggest population

based near Banks Peninsula.

Commercial fishing, particularly through the use of gillnets, has

contributed to their declining numbers.

Ms Fitzsimons said more research into the North Island Hector's

dolphin population was needed urgently.

``We desperately need more research to tell us exactly where the

North Island dolphins are, how many there are and what's killing

them,'' Ms Fitzsimons said.

``In the meantime we need a Hector's dolphin sanctuary

controlling gillnetting and trawling from Kawhia to the mouth of the

Kaipara Harbour.''

Auckland University senior lecturer Scott Baker, who supervised

the research done by doctorate candidate Franz Pichler, said figures

for the North Island Hector's dolphin population were

an estimate only, because there had been so little research.

He said the dolphin would probably be extinct on the North Island

within 10 generations if nothing was done to reverse the trend of

declining numbers.

Commercial fishing, particularly through the use of gillnets, has

contributed to their declining numbers.

Ms Fitzsimons said more research into the North Island Hector's

dolphin population was needed urgently.

``We desperately need more research to tell us exactly where the

North Island dolphins are, how many there are and what's killing

them,'' Ms Fitzsimons said.

``In the meantime we need a Hector's dolphin sanctuary

controlling gillnetting and trawling from Kawhia to the mouth of the

Kaipara Harbour.''

Auckland University senior lecturer Scott Baker, who supervised

the research done by doctorate candidate Franz Pichler, said figures

for the North Island Hector's dolphin population were

an estimate only, because there had been so little research.

He said the dolphin would probably be extinct on the North Island

within 10 generations if nothing was done to reverse the trend of

declining numbers.

Dr Baker said the research by Mr Pichler suggested the North and

South Island reproduced only among themselves.

``What Franz has established is that the North Island population

is distinct genetically from the South Island.''

That meant it was unlikely North Island numbers would be restored

by migration from other areas since the research suggested little or

no breeding between dolphins from different parts of the country.

``If they disappear from the area here they simply would not

return and that's our primary criteria for their importance.

Dr Baker said the research by Mr Pichler suggested the North and

South Island reproduced only among themselves.

``What Franz has established is that the North Island population

is distinct genetically from the South Island.''

That meant it was unlikely North Island numbers would be restored

by migration from other areas since the research suggested little or

no breeding between dolphins from different parts of the country.

``If they disappear from the area here they simply would not

return and that's our primary criteria for their importance.

``The historical evidence tells us they're simply not moving

between the areas and they're not reproducing, they're not

interchanging genes and they're not moving physically.

``Based on that historical evidence

-- that is, we assume that's been the case over the past hundreds,

thousands of years -- if this little group goes extinct they just

won't come back.''

Dr Baker said the North Island dolphins had different markings,

and were larger, than the South Island population and there had been

speculation over many years that they were a different species or

subspecies to the South Island dolphin.

``The historical evidence tells us they're simply not moving

between the areas and they're not reproducing, they're not

interchanging genes and they're not moving physically.

``Based on that historical evidence

-- that is, we assume that's been the case over the past hundreds,

thousands of years -- if this little group goes extinct they just

won't come back.''

Dr Baker said the North Island dolphins had different markings,

and were larger, than the South Island population and there had been

speculation over many years that they were a different species or

subspecies to the South Island dolphin.

Evidence from Hector's dolphin deaths off the North Island

coast, suggested their numbers may already have deteriorated to the

point where problems related to a dying species, such as inbreeding,

were beginning to occur.

``In recent years animals that have washed up dead on the

beaches, of the five or six I can think of

... several of them have been adult females with young calves and

that is a little bit troubling because that's not common in the

South Island.

Evidence from Hector's dolphin deaths off the North Island

coast, suggested their numbers may already have deteriorated to the

point where problems related to a dying species, such as inbreeding,

were beginning to occur.

``In recent years animals that have washed up dead on the

beaches, of the five or six I can think of

... several of them have been adult females with young calves and

that is a little bit troubling because that's not common in the

South Island.

``That would be consistent with an inbreeding effect; that

animals are having difficulty with birth or neonatal mortality and

that sometimes carries the adult along with them.

``But we can't say with much certainty -- when you get a

population this small generalisations are hard.''

Dr Baker said more research was needed to discover why the

dolphins were dying but it wasn't always easy to get funding.

The first stage of the university's work was funded by grants

from the Worldwide Fund For Nature and the Department of

Conservation.

The next stage of the research would be to collect DNA samples

from North Island dolphins in an information-gathering exercise,

which would also allow their population to be tracked over time, Dr

Baker said.

``That would be consistent with an inbreeding effect; that

animals are having difficulty with birth or neonatal mortality and

that sometimes carries the adult along with them.

``But we can't say with much certainty -- when you get a

population this small generalisations are hard.''

Dr Baker said more research was needed to discover why the

dolphins were dying but it wasn't always easy to get funding.

The first stage of the university's work was funded by grants

from the Worldwide Fund For Nature and the Department of

Conservation.

The next stage of the research would be to collect DNA samples

from North Island dolphins in an information-gathering exercise,

which would also allow their population to be tracked over time, Dr

Baker said.

But the university was yet to hear back from the WFN and DOC over

a proposal for funding it put up in March.

The Public Good Science Fund had responded to funding requests in

the past with the response that any such funding had to come from

DOC.

``So work that we consider fundamental science on biodiversity

and the environment and endangered species, they (the Public Good

Science Fund) view as a DOC management issue.

``We don't seem to be easily eligible for that kind of thing and

I think that's a flaw in the system because DOC has got huge

responsibilities and very limited funding.''

Ms Fitzsimons said DOC didn't have enough money to do its job.

``The little money DOC has for the Hector's dolphin has gone to

sustaining the South Island subspecies.''

The North Island researchers have been able to continue only

thanks to private organisations like the Worldwide Fund for Nature

and have even forced to fund some research out of their own

pockets.''

The Green Party today released its conservation policy, with a

North Island sanctuary among its measure

But the university was yet to hear back from the WFN and DOC over

a proposal for funding it put up in March.

The Public Good Science Fund had responded to funding requests in

the past with the response that any such funding had to come from

DOC.

``So work that we consider fundamental science on biodiversity

and the environment and endangered species, they (the Public Good

Science Fund) view as a DOC management issue.

``We don't seem to be easily eligible for that kind of thing and

I think that's a flaw in the system because DOC has got huge

responsibilities and very limited funding.''

Ms Fitzsimons said DOC didn't have enough money to do its job.

``The little money DOC has for the Hector's dolphin has gone to

sustaining the South Island subspecies.''

The North Island researchers have been able to continue only

thanks to private organisations like the Worldwide Fund for Nature

and have even forced to fund some research out of their own

pockets.''

The Green Party today released its conservation policy, with a

North Island sanctuary among its measure

The fishermen of Futo, Japan, brought in a profitable catch last week: dozens of dolphins herded into a circle of nets and driven toward shore.

The sea runs red with dolphin blood after the massacre.

The fishermen of Futo, Japan, brought in a profitable catch last week: dozens of dolphins herded into a circle of nets and driven toward shore.

The sea runs red with dolphin blood after the massacre.

Most of the captured animals are about to meet a brutal and heartbreaking end. But a few of the best are worth as much as $30,000 to meet a growing international demand for captive dolphins.

Most of the captured animals are about to meet a brutal and heartbreaking end. But a few of the best are worth as much as $30,000 to meet a growing international demand for captive dolphins.

At a marine park near Tokyo, the dolphins put on the kind of show that is now a staple of aquariums and amusement parks around the world. But that's not the whole story.

For those dolphins left behind last Thursday the killing was about to begin.

Those dolphins not young enough or attractive enough for marine parks were about to be turned into meat and fertilizer. Some trucked away were still alive.

At a marine park near Tokyo, the dolphins put on the kind of show that is now a staple of aquariums and amusement parks around the world. But that's not the whole story.

For those dolphins left behind last Thursday the killing was about to begin.

Those dolphins not young enough or attractive enough for marine parks were about to be turned into meat and fertilizer. Some trucked away were still alive.

"It's an unbelievable act of cruelty to an animal that I really love," says Hardy Jones, a documentary film maker, who has photographed the same kind of capture as that occurring last week.

"And to watch it happen the only thing I can do is say to myself, 'Take the pictures and get them out so the world can see,'" he says.

If the world is outraged, it's because so many have come to know dolphins so well in captivity at parks like Sea World in San Diego.

"People can come here and learn about dolphins, experience them first hand, interact with them personally," says Jim Antrim of Sea World. "I think that's leading to a better level of understanding and appreciation for them."

American law forbids importing wild dolphins. Those at Sea World were bred in captivity. But continuing international demand is still leading to the slaughter of animals known as gentle, intelligent and friendly.

"It's an unbelievable act of cruelty to an animal that I really love," says Hardy Jones, a documentary film maker, who has photographed the same kind of capture as that occurring last week.

"And to watch it happen the only thing I can do is say to myself, 'Take the pictures and get them out so the world can see,'" he says.

If the world is outraged, it's because so many have come to know dolphins so well in captivity at parks like Sea World in San Diego.

"People can come here and learn about dolphins, experience them first hand, interact with them personally," says Jim Antrim of Sea World. "I think that's leading to a better level of understanding and appreciation for them."

American law forbids importing wild dolphins. Those at Sea World were bred in captivity. But continuing international demand is still leading to the slaughter of animals known as gentle, intelligent and friendly.

�1999, CBS Worldwide Inc., All Rights Reserved.

�1999, CBS Worldwide Inc., All Rights Reserved.

Dolphin Decision. On Apr. 29, 1999, Secretary of Commerce William Daley

issued a rule that would allow fishermen who use of tuna seines to

surround dolphins in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to be labeled such

tuna as "dolphin-safe" as long as no dolphins are observed to be killed or

seriously injured. This decision was taken after U.S. managers determined

that there was insufficient evidence that such fishing had a significant

adverse effect on dolphin populations. [American Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty of Animals press release, Assoc Press, NOAA press

release]

Dolphin Decision. On Apr. 29, 1999, Secretary of Commerce William Daley

issued a rule that would allow fishermen who use of tuna seines to

surround dolphins in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to be labeled such

tuna as "dolphin-safe" as long as no dolphins are observed to be killed or

seriously injured. This decision was taken after U.S. managers determined

that there was insufficient evidence that such fishing had a significant

adverse effect on dolphin populations. [American Society for the

Prevention of Cruelty of Animals press release, Assoc Press, NOAA press

release]

Double click on picture in cube to go to:Seashepherd org,Friends of the Ocean,D.E.E.P Online,Cetacean Society International,Save the dolphin,Pam for the love of dolphins

Double click on picture in cube to go to:Seashepherd org,Friends of the Ocean,D.E.E.P Online,Cetacean Society International,Save the dolphin,Pam for the love of dolphins

Enter into the world of Seals!

Enter into the world of Seals!

Enter into the world of Seals!

Enter into the world of Seals!