from "Constructing Public Opinion - How Politicians and the Media Misrepresent the Public"

I want to talk to you about a little problem called the language barrier. Have you ever given much thought to how difficult it must be for non-native English speakers to learn English so they can participate in international discussions, get jobs in English-dominated sectors such as IT, or immigrate to (or visit) English-speaking countries? Have you ever wondered how the international news you get on TV or in newspapers might be distorted by poor translations and by the extra "spin" added by English media? Have you ever wondered what the billions who cannot speak English might say to us, if only we could understand them? Have you ever heard of someone being charged with a crime but unable to defend himself against the charges because he doesn't speak the local language? Have you ever resisted going to a foreign country because you're afraid of being unable to communicate?

I believe that human communication should be considered a basic human right. I believe that the world needs a universal second language.

If you agree, please visit onetongue.org and register your support.

I strongly believe that the universal language should be something a heck of a lot easier than English.

First of all, English is not as universal as some people think. It is only the third most common language behind Mandarin and Spanish. Only about 5.4%* of the world's population speaks it natively, and only 9.6% know it as a second language. Heck, English isn't even universal in the U.S.

English is difficult, even among natural languages, and is many times more difficult than any constructed auxilliary language. Here are some of the things that make it difficult:

A few months ago I had never heard of Esperanto. The day I learned of its existence was the day I decided to learn it.

Esperanto is the easiest living language to learn in the world*; after I studied it just five months in my free time, already I could write most of what I am saying now, in Esperanto, without a dictionary. Although I write slowly in Esperanto, and lack a large vocabulary--even so, in a perfect world where everyone knows Esperanto, I could travel around the world and communicate with anyone.

Esperanto is my second language after English. I've always wanted to know what it's like to think in another language, and soon I hope to find out. Before Esperanto I couldn't decide what language to learn: any one language is of little use outside the area in which it is spoken. If I learned French it would be useful only in Quebec, France, and other French-speaking places; if German, it would be of little use outside Germany; if Spanish, I'd be limited to Spain, Mexico and maybe some of those South American nations I know nothing about. Now, Esperanto has few speakers, but they are scattered throughout the world and can be met on the Internet. So, I expect, through this language I can get a taste of any culture I like--either by talking to an Esperantist online, or by travelling to a country and getting a tour from one.

I have read that one can learn a third language more easily than a second, and Esperanto is one of the easiest routes to that second language. I read of an experiment where a group of students were taught Esperanto for one year and French for three. Afterward, test scores showed that those who learned Esperanto were better at French than a control group that learned French for four years. While presumably any second language would provide some benefit in learning a third, only Esperanto can be learned so quickly that it can be added to a curriculum without adding classroom hours.

Personally, I see another benefit to Esperanto: if taught properly, it can be used to break some of your silly English habits. When you learn Esperanto you are learning a far more logical language than English, and thanks to the grammar codings you get a kind of lesson in grammar every time you speak it. If you take French as a second language, for instance, you will find yourself attempting to translate from English to French and back--from one complicated language to another complicated, but entirely different, language. I figure, if you learn to speak Esperanto fluently, and then French, your brain need only deal with the complications of French, not English.

Esperanto is more fun to learn than any other language. This is because you can start saying things with it almost immediately. You don't have to study conjugations (whatever those are) or memorize complicated and random rules; you learn a few words, and a few simple rules, and after a little practice, you can not only write correct sentences, but you can be sure that they are correct, without having an expert check your work.

Last but not least, if Esperanto were widely adopted, it could eliminate the language barrier. I did not properly realize how significant the language barrier is until I read some essays of Claude Piron, a former U.N. translator. He has a lot of interesting things to say on the subject; there are many essays but this frustrated tirade is a good place to start your enlightenment.

"In society as it is now organized at the global level, if you want to avoid all psychological disturbances or handicaps linked to language, there remains only one means: to be a native speaker of English."

It's understandable that I have not given much thought to language barriers in the past, as I'm a native English speaker living in a place where almost everyone speaks English for a thousand miles around, and working in a profession (computer programming) where English is nearly universal. In fact, the only place I recall encountering the language barrier in an important way was at the University of Calgary, where perhaps the majority of professors spoke English as a second language. Most of them had a good grasp of English terms and grammar, but spoke with such thick accents that I could scarcely understand them; a few professors, and far too many TAs (teaching assistants), even had difficulty finding the words to speak, and understanding students. On the teacher-evaluation sheets given to us, I criticized the professors for their poor English, but truly I only wanted to blast the university for hiring ESL teachers on a continent of millions of native English speakers. "Surely," I wrote, "there are enough native English speakers in North America to fill the university's needs?" The learning environment at the university is poor even with a native English speaker heading the class; when impaired communications are added, I start to get really mad.

Now, probably, the universality of English in my region is an illusion. From my point of view, the language barrier only appears when people open their mouths. The janitor I walk by in the hall, the cook at McDonald's, the immigrants who rarely leave home--if they don't speak to me, I am none the wiser. I am rather curious how many non-native-English-speaking people actually live around here. It's understandable that they don't want to talk, since they correctly fear that they cannot express themselves or understand what is said to them. When a non-native speaker tries to communicate, he may feel inferior, appear to be less intelligent than he is, and annoy the native with whom he is trying to communicate, all at the same time--even if he has devoted thousands of hours to studying English!

Is this fair? No. Does it have to be this way? No.

Whenever I try to point out something isn't fair, somebody always responds dismissively: "So what? Life isn't fair. Deal with it."

But people who say this ignore the fact that if we, as a people, were willing, we could eliminate all the greatest things that make life unfair. Most unfairness is man-made. It is our fault. Although systematic unfairness is often caused by a small minority, if a large enough number of people stood up and demanded better, they could have it. But when people say "Deal with it", they don't really mean it. They don't mean "deal with the problem", to eliminate it; instead they mean "accept it as a given".

Besides, despite all our talk, in the first world, of equality and justice for all, we are really only talking about ourselves. If a genocide happens somewhere in Africa--Rwanda, that's somewhere in Africa, isn't it?--and, say, 800 000 die, it is a news item that gets no more airtime than the adjacent news item about the latest celebrity scandal. The World Health Organization reports that eleven million young children die each year, mostly from preventable causes. I never heard that on the news; the press release only turned up on some Google search I was making. You could blame the media, but it seems to me that media outlets, especially the big ones, are mainly out to turn a profit. If they choose stories based on what they think will get the most viewership or readership, it seems to me that the way preventable major world disasters are ignored is the fault of the people at large. It is our fault because, as a whole, we prefer to ignore such disasters rather than try to prevent them. Especially ignored are ongoing disasters, things like world hunger, giant refugee camps, and child slave labor. Somehow, a constant presence of suffering and death is more acceptable to us than something that happens only once.

But you might say, "What's the point of putting these stories on the news? They just make me depressed, and do nothing to stop the disasters!" It's true that news stories don't do anything directly. However, they promote awareness, and awareness breeds action. We first-world people live in democracies, do we not? We may not have the best electoral system, but if all of us stood up and demanded something be done about world hunger, even at the cost of higher taxes, then something would most certainly be done.

It doesn't happen because it is not a priority for us.

According to an article in The Globalist, industrialized nations spend an average of $7 on the military for every $1 they spend on foreign aid, as of 1999. Thus, to double foreign aid would only cost as much as a 14% increase in military spending. But the U.S., in particular, deserves to be singled out. I've read that the U.S. spends 0.1% of its GDP on foreign aid, or $33 per American, but it spends 30 times more on its military--again, as of 1999, and you can be sure military spending has gone up since 9/11. If the U.S. met the bombs-to-bread ratio of other industrialized nations, it would spend $48 billion in foreign aid each year, and it would singlehandedly double the world total spent on foreign aid. America had a chance to rebuild Afghanistan after warring with it, but of course, it did not, instead choosing to start a war with Iraq. More.

And if I may digress for a speculation, I suspect there's something terribly wrong with how foreign aid money is spent, as though the money were a political gesture and no one's actually trying to find the best use for the money. I particularly worry that insufficient care is taken to ensure that the people, rather than their corrupt governments, get the fruits of foreign aid money. I wish I knew enough to say more on the issue. More.

Anyway, what the heck does all this have to do with IALs? Well, for the most part I'm just ranting in frustration, but the Language Barrier does play a role in all this. It is just another example of how humanity has failed to deal with a big problem that is entirely solvable. It is an example of how people ignore important issues because they don't want to go to the trouble of solving them.

In the case of the language barrier, it may simply be that

people are not aware that it is a problem or it can be solved.

After all, I was not aware of the problem until recently. Yet,

why are they not aware? The reason, it seems to me, is that when

Joe Sixpack--the average citizen--learns of the problem, he

generally does not pass his newfound knowledge to others. If

Average Joe cared enough, he would tell his friends and the idea

would begin, and continue, to spread. The fact that the idea does

not spread makes me suspect that most people just don't give a

rat's ass about the problem.

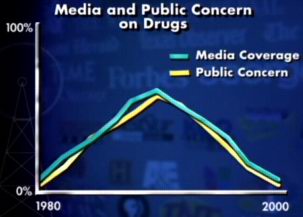

On the other hand, maybe it's just that people don't like to be grass roots: they aren't willing to support issues and spread ideas themselves, instead relying on the mainstream media to decide what's important. I saw an interesting graph recently which showed an almost perfect correlation between media coverage of the drug problem, and the degree to which polls indicated public concern. In other words, people are too passive to look for information outside the mainstream media, and base their opinions solely on what they see there. The media thus has tremendous power, yet it lacks the discipline and the will to use that power responsibly.

The language barrier inhibits communication, and in the age of the internet where anyone with a computer can tell their story online, billions of people cannot usefully do so, because they cannot write effectively in the languages of the most powerful nations. How can a global villiage exist when you cannot talk to your own neighbor? In a true global villiage, anyone anywhere could be your neighbor, in a sense; but in the real world, there are places where you can't talk to your physical next-door neighbor because you don't speak the same language.

There is something depressing in watching two Africans trying to communicate by gestures, when one, a Rwandan – with Kinyargwanda as his mother tongue – has made the effort of assimilating Swahili and French, and the other, a Nigerian, is capable of using, besides the Agatu of his native village, three languages as important as Hausa, Arabic and English. The total of languages spoken by the two of them amounts to seven, and they have devoted many hours for many years to drilling themselves in the correct handling of difficult rules of grammar and inconsistent vocabularies. Yet they stand together as though separated by an insuperable barrier. (C. Piron)

There's also the cost of learning second languages. Can you imagine how much it costs for the people of the world to learn second languages? I don't have numbers, but hey, it must be pricey.

...10,000 hours of study and practice are needed to possess any national language. If readers doubt the validity of that figure, they may get a confirmation by observing the language of a six or seven year old child speaking its mother tongue. Even after some 10,000 hours of full immersion in the language, it will utter such forms as I comed, he falled, mouses, foots, when I'll go, it's mines, etc.... The brain tends to generalize spontaneously all linguistic signs it has perceived. So a child or a foreigner who has (unconsciously) registered the regular appearance of a final -s in the series yours, hers, ours, theirs will have the natural reflex to apply the same pattern to the first person singular: he or she will say mines. For the correct form to be introduced, a new, conditioned reflex, has to override the natural one. (C. Piron)

Esperanto is a second language, but it is so simple compared to others that the cost of learning it as a second language can be absorbed into the cost of learning a third, as I described above. Better yet, the third language could be dropped altogether and a ton of time and money could be saved by billions of people. Even if we in the first world do not learn it, if it were to be taught in the third world, where a great many languages are used now, it would allow them to communicate among themselves. It is hard to estimate what the benefits of this could be, but I believe they may be profound.

Our society, wistfully, or perhaps arrogantly, supposes we could get this language problem out of the way if only everyone were to learn English (though only 8 percent of the world speaks it natively). But English is much more complicated than many of us realize, especially if we've never tried to learn a comparably complicated language like French. As well as having a very large vocabulary, there are also a large number of idioms, and a great many words are loaded with several meanings and are used ambiguously in everyday speech. It also has a number of irregular plurals, a highly inconsistent system of affixes (prefixes and suffixes), and a spelling system so irregular and complicated that many native speakers frequently misspell after using English their entire lives! And I, though a good spellar, need to look up English words in a dictionary on a regular basis. I have Chinese roommates that ask me every day about the meaning of some word or the grammar of some sentence, and frequently I am at a loss to explain it to them because of the subtlety involved. Just last night, my roommate Micheal was reading an article aloud. He said "to some extent", with "ext" stressed, and I corrected him: "to some extent". He got it after a little practice, and then along came another sentence with the word "some" in it, and I corrected him again... "no, the word some is not stressed here, see, just in that one phrase 'to some extent'". His learning process, and trying to explain the subtleties of our words and phrases, has given me some idea how complicated English really is.

It is important to be aware of the grave inequality between those who speak a language natively and those who do not. If you don't know of this, I suggest reading this article from Claude Piron, especially the bottom half. Esperanto has a way of at once equalizing and empowering people: equalizing, because virtually all who speak it speak it as a second language, thereby putting no one at an unfair disadvantage; and empowering, because it can be used to communicate the full spectrum of human thought effectively.

Esperanto isn't the only solution to the language barrier: the bottom line is that any very easy language would do the trick, and there exist other designs that are easier, especially for people who do not know English or a Romance language. Plus, Esperanto has an alphabet with characters that cannot be typed directly on any keyboard: ĉ ĝ ĥ ĵ ŝ (and ŭ can be problematic). Finally, I find Esperanto to be very long winded, because most words, even extremely common words like is, less, this, that, who, can, etc. are at least two syllables.

But Esperanto is a decent solution because it is well developed. It has been used for over a hundred years with good results anywhere it was used. And whether you decide to learn it or not, I urge you to keep an open mind about it. And to tell your friends. It is perhaps more important to spread the idea of an IAL than to actually learn one. Most people don't want to learn a constructed language like Esperanto until there is already a large number of people who speak it; it's a classic chicken-and-egg problem. The solution, I think, is to spread the idea as vigorously as possible, because arguing for the the idea takes almost no time commitment, unlike actually learning an IAL. If the idea becomes popular among enough people, the mainstream media will begin to cover it, causing awareness of the idea among still more people, until finally, hopefully, the leaders of democratic nations can at last be convinced to standardize on a common language. Once the world decides what the common language shall be, people will then be willing to learn it en-masse, no longer having to fear that no one will understand the language they're learning.

So: spread the word.

If you want to learn Esperanto, try these sites:

--- In Esperanto --- { stuff in braces is stuff I that was not defined in my crappy vortaro }

Antaux kelkaj monatoj, mi neniam konas Esperanton. La tago kiam mi lernis la vorton "Esperanto", estis la tago ke mi decidis lerni gxin.

Esperanto estas la plej facila vivanta lingvo en la mondo; post ke mi studis gxin kvin da monotoj, en mia libera tempo, jam povas mi skribi cxi tiel bone. Kvankam mi ne skribas rapide, kaj ne scias mi grandan vortaron, tamen mi povas diri multan, kaj povas komuniki suficxe bone ke, se the mondo estus perfekta, kaj cxiu scius Esperanton, mi povus vojagxi cxirkaux la mondon, kaj komuniki kun ajn iu.

Esperanto estas mia dua lingvo post Angla. Mi cxiam volis scii la sinsenton de scii alian lingvon, kaj baldaux mi esperas eltrovi. Antaux Esperanto, mi ne povis decidi kiun lingvon kiu mi devis (should) lerni: ajn iu lingvo ne estas utila ekster la lokoj kie homoj gxin parolas. Se mi lernus la Franca, ne estus utile ekster Quebec, Francio, kaj aliaj francaj landoj; se la germana, ne estus utile ekster Germanio; se la hispana, mi estus limigata al Hispanio, Meksiko kaj eble kelkaj sudamerikaj nacioj. Nu, Esperanto havas malmultaj parolantoj, sed ili estas disa tra la tuta mondo, kaj oni povas renkonti ilin en la interreto. Tial mi opinias, ke per tiu cxi lingvo, mi povas preni gusto de ajn iu kulturo kiun mi volas, aux per babili kun esperantisto enrete, aux per vojagxi al lando kaj ricevi 'turneon' de unu.

Mi legis ke oni povas lerni trian lingvon pli rapide ol duan, kaj Esperanto estas la plej rapida vojo al dua lingvo. Mi legis pri eksperimento en kiu lernantopo estis instruita Esperanton dum unu jaro, kaj poste la Franca dum tri jaroj. Kaj, alia lernantopo estis instruita nur la Franca dum kvar jaroj. Tamen, poste, ekzamenoj manifestis ke la unua opo estis pli bona je la Franca. Kvankam supozeble ajn iu dua lingvo donus gajno por lerni trian, nur Esperanton povas lerni tiel rapide ke gxin povas aldoni al instruprogramo sen aldoni klascxambrajn horojn.

Laux mi, estas alia gajno de Esperanto: se instruata dece, gxi povas esti uzata rompi kelkajn da via kuriozaj Anglaj kutimoj. Kiam vi lernas Esperanton, vi lernas multe pli logikan lingvon ol la Angla. Kaj dankon al la gramatikaj finajxoj, vi ricevos lecionon de gramatiko cxiu okazo ke vi parolas gxin. Se vi eklernas la Franca por dua lingvo, ekzemple, vi trovigxas provante traduki de Angla al la Franca kaj reen--de unu malsimpla lingvo al alia malsimpla, sed tute malsama, lingvo. Mi supozas, ke se vi lernas paroli Esperanton bone, tiam la Franca, tiam via cerbo nur bezonas trakti (alpasxi) la malsimplecon de la Franca, ne Angla ankaux.

Esperanto estas pli plezura lerni ol ajn iu alia lingvo. Estas cxar vi povas komenci diri ajxojn per gxi preskaux tuj. Vi ne devas studi {conjugations}n, (kio ajn tiuj estas) aux parkeri preskriboj komplikaj/malsimplaj kaj hazardaj; vi lernas kelkaj vortoj, kaj kelkaj simplaj preskriboj, and post kelka praktikado, vi ne nur povas skribi korektajn frazojn, sed ankaux vi povas esti certa ke korekta ili estas, sen havi fakulon kontroli vian laborajxon.

Laste, sed ne malplejgrave, se Esperanto estus vaste alprenita, gxi povus malkrei la lingvan barieron. Mi ne bone komprenis kiel signifa la lingva bariero estas gxis ke mi legis kelkajn artikolojn de Claude Piron, eks-UN (Unuigitaj Nacioj) tradukisto. Li havas multajn interesajn ajxojn diri je la temo; estas multaj artikoloj sed cxi tiu plenfrustra artikolo estas bona ejo kie komenci vian erudadon.

"En socio kiel gxi estas ordata nun cxe la monda nivelo, se vi volas eviti cxiujn psikologialajn perturbojn aux handikapojn rilate al lingvo, ekzistas ankoraux nur unu rimedo: havu la Anglan kiel vian unuan lingvon."

Estas kompreneble ke mi ne donis multan penson al lingvalaj barieroj estintece, cxar mi estas {native} parolanto angla en lando kie la Angla estas preskaux universala cxirkaux apenaux mil kilometroj, kaj kiam mi laboras en profesio (komputila programado) kie la Angla estas preskaux universala, ecx tutmonde. Fakte, la nura ejo kie mi memoras renkonti (renkontinte??) la lingvan barieron je grava maniero estis cxe la universitato de Calgary, kie eble la plej de la instruistoj parolis kun tiel peza {accent}oj, ke mi preskaux ne povis kompreni ilin; malmultaj da instruistoj (profesoroj) kaj ja tro multaj TAoj (instruistaj helpantoj) ecx parolis kun granda malfacileco, kaj sxajne ofte ne povis kompreni studentojn. Sur la instruist-jugxa papero, mi kritikis la profesorojn pri ilia malbona Angla, sed vere mi nur volis kritiki la universitaton por ki ili luis dualingvajn instruistojn sur kontinento de milionoj da {native}aj Anglaj parolantoj. "Certe," vi skribis, "estas suficxe da {native}aj Anglaparolantoj en Nordameriko por plenumi la bezonojn de la universitato?" La lernada medio cxe la universitato estas jam malbona kun {native}angla instruisto regi la klason; kiam nefunkciantan komunikadon oni aldonas, mi komencas esti tre kolera.

Nu versxajne, la universaleco de la angla estas nur pseuxdajxo. Laux mia vidpunkto la lingva bariero aperas nur tiam, kiam homoj malfermas iliajn busxojn. La {janitor} (eja-purigisto?) preter kiu mi promenas en la koridoro (halo?), la kuiristo cxe McDonald's, la enmigrintoj kiuj malofte lasas iliajn hejmojn--se ili ne parolas al mi, tiam mi estas cxiam nekonanta.

Mi estas iome scivola, kiom multaj ne{native}aj anglaj parolantoj logxas cxirkaux cxi tie. Estas kompreneble, ke ili ne volas paroli, estante ke ili korekte timas, ke ili ne povas sinespremi, aux kompreni tion kion oni diras al ili. Kiam ne{native}a parolanto penas komuniki, gi (ri) eble sentas sin malsupera, eble sxajnas malpli inteligenta ol gi vere estas, kaj cxagreni la homon, kun kiu gi parolas--cxio cxi cxe samtempe--ecx se gi aldonis milojn da horoj al studi la Anglan!

Cxu cxi tio estas justa? Ne. Cxu aferoj devas (must, not should) esti cxi tiel? Ne.

Kiam ajn mi provas montri ke io ne estas justa, iu cxiam respondas {dismissively} (~ignore): "Tio ne gravas. La vivo estas nejusta." -- kaj uzante la kutiman anglan idiomon -- "Traktu gxin."

Sed la plej homoj, kiuj diras tion, ignoras la fakton, ke se ni, kune kiel popolo, estus volanta, ni povus neniigi cxiujn de tiuj aferoj, kiuj igas la vivon nejusta. La plejparton de disvasta nejusteco igas malmultaj homoj, kaj se suficxe granda aro da homoj ekstarus kaj petus plibonecon, ili ekhavus gxin. Sed malfelicxe, kiam oni diras "Traktu gxin", oni ne volas diri "Traktu la problemon", por elimini gxin; anstataux oni volas diri, "akceptu aux premisu gxin".

Krome, malgraux la paroladon ni faras, cxi tie en la ricx-mondo, pri egaleco kaj justeco por cxiuj, ni vere nur parolas pri ni mem. Se "genocido" (popolmurdado) okazus en Afriko--nome {Rwanda}--kaj 800 000 homoj mortus, tiam tio estas novajxo kiu ne gajnas pli atenton ol la plej fresxa novajxo pri iu famula klacxacxo. La Mond-Sana Organizo (WHO) raportis ke dekunu junaj homoj mortas cxiu-jare, plejparte de preventeblaj kauxzoj. Mi neniam auxdis tion je la televida novajxo; la "ellasajxo-por-gazetaro" nur trovigas en retsercxo mia. Oni povus kulpigi la novajxfaristoj, sed sxajnas al mi ke ili, speciale la plej grandaj el ili, simple volas profiti per ajn elba vojo. Se ili elektas rakontojn laux tio, kio, ili opinias, generos la plej grandan vidantaron aux legantaron, tiam sxajnas al mi, ke la ignoreco de preventeblaj mondkatastrofoj estas la kreitajxo de la tuta socio. La kulpo apartenas al ni, cxar ni, gxenerale, preferas ignori cxi tiujn katastrofojn anstataux provi preventi ilin. Speciale ignoritaj estas la cxiam-okazantaj katastrofoj, la gravaj problemoj kiuj okazas jare-post-jare, problemoj kiel mondmalsateco, grandegaj rifugxintaj kampoj, kaj la infana laboro. Iel, konstanta estanteco de suferado kaj mortado estas pli akceptebla al ni ol io, kio okazas nur unufoje.

Sed vi eble pensas, "Kion atingas, meti cxi tiujn rakontojn en la novajxojn? Ili nur igas min malfelicxa, kaj ne ecx iomete haltigas la katastofojn!" Estas vere, ke novajxaj rakontoj ne faras ajn ion rekte. Sed ili igas konantecon--konsciecon--kaj konscieco kauxzas agon. Ni ricxmonduloj logxas en demokratilandoj, cxu ne? Ni eble ne havas la plej bona balotan sistemon, sed se ni cxiuj starus kaj petegus ke oni faru ion pri la mond-malsato, ecx kun la kosto de pli altaj impostoj, tiam certe ion oni farus.

Tio ne okazas, cxar gxi ne estas suficxe grava por ni.

Laux artikolo en "La Mondalisto", industrialaj nacioj elspezi (averagxe) sep dolaroj (usonaj) por la militistaro je (angle per) cxiu unu dolaro, kiun ili elspezas por fremdahelpo (helpo por malricxaj landoj), laux 1999 nombroj. Tial, duobligi fremdahelpon bezonus nur tiom multan monon, kiom estus bezonata por plialtigi militan elspezon je (by) 14%. Sed la Usono, speciale, meritas esti kritikata. Tiu lando elspezas 0.1% de gxian GDP (?tutlanda produkto financa?), aux $33 de cxiu usonano, al fremdahelpo, sed gxi elspezas 30-obla al la militistaro--denove, laux 1999 nombroj, kaj oni povas veti, ke la militistaro gajnis multe pli da mono post Septembro 11. Se Usono atingus la bomboj-je (vis-a-vis, versus, to)-pano {ratio} de Euxropaj nacioj, ili elspezus $48 bilionoj da dolaroj por fremdahelpo cxiujare, kaj gxi per si mem duobligus la tutmonda elspezado fremdahelpa.

Krome, Usono havis la {oportunity}n rekonstrui Afganion post gxia milito kontraux gxi, sed gxi elektis, nature, ne fari tion, sed anstataux komenci militon kontraux Irakio.

Cxiukaze, kiel cxi cxio rilatas al Esperanto? Nu, plejparte, mi simple kolere krias de fustreco, sed la lingva bariero havas rolon en tiu cxi afero. Gxi estas simple alia ekzemplo, montrante ke homoj ignoras gravajn aferojn cxar ili ne volas gxeni sin batali la problemojn.

Whew. All this translation is making me tired. I'll stop now.

Things I would like to see in Esperanto (but this is just my newbie komencantala opinion, I don't expect anyone to pay attention. And I must stress, the particular morphemes to express these ideas are not important to me. I only care that short morphemes exist; I don't care what they actually are.)

As language is used, it tends to get shorter because people hate to use many syllables to express simple thoughts. Esperanto presents a problem because most words are at least two syllables. As a result, speakers have made extensive use of adverbs to replace prepositional phrases, and compound words to eliminate grammatical endings. This works well enough for longer sentences, but these techniques rarely work for short sentences. I believe short, simple phrases are still too long and, to reduce them further, shorter versions of existing words should be introduced. I am concerned that if Esperanto is ever widely adopted, speakers will (collectively) create their own local dialects to shorten the language and may even break the rules of Esperanto, such as by omitting grammatical endings, to save syllables. I believe this is very undesirable.

I think someone should analyze the most common words, especially in conversations, and I think those words should be shortened. Also, any research done should pay particular attention to cases where words are slurred. People naturally slur their speech somewhat, occasionally changing i to j, or changing a vowel such as e to a. Provided that such slurring does not make speech more difficult to understand, the most common slurs across the world should be made official. If everyone says kju rather than kiu, for instance, why not make it official?

It is also worth mentioning that shorter words are more useful in compound words; thus, any root that may be useful in compound words should be limited to one syllable, or two at worst. The root for need, bezon-, is two syllables and I believe this is why it rarely forms part of a compound word. Whenever a compound word is impractically long, an entirely new root is required instead; and every time a new word root comes into the Esperanto, it becomes slightly harder to learn. Esperanto should be an easy language. Esperantists should do everything they can to prevent it from getting ever harder. The fact that new roots come from European languages is no solution; for Esperanto is not supposed to be a European language, but an international one.

Here are some suggestions that might be good (though I have not undertaken any formal analysis myself):

(I also suspect the practice of changing verb forms into adjectives to avoid estas is negative for two reasons:

Ajxoj mi volas esti en Esperanto:

...todo...