JOURNAL - Page 8

Vesak 2001

ARTICLES INDEX - PAGE 8

- Some salient features of Buddhism - The foundations of Buddhism are the four Noble Truths...

- NIRVANA - Nirvana is a state of supreme happiness...

- What should be the Vesak determination? - The first Vesak of 21st Century dawns on May 7 in 2001...

- Revolt against false values - If you were to examine the values in which you have been nurtured...

- Let the Dhamma be your refuge - The birth of a child brings joy to his parents...

- The significance of Vesak - ...lies with the Buddha and his universal peace message to mankind...

- The Bodhi-Puja - The veneration of the Bodhi-tree...

- What did the Lord Buddha teach? - The only person who could answer the question...

- Meditation On Mindfulness - I will try to explain, from Buddhist point of view, mindfulness and its development...

- Why Vesak is significant for the global society? - Today, society is riddled with a multitude of religions...

- The Art of giving - One of the challenges that life offers is to find a purpose...

- Transient are all formations; strive zealously - The Vesak full moon shines proudly in the...

- Navigating the New Millennium - Although our calculation of time's passage in years and centuries...

- Reflections on the Five Aggregates (Khandhas) in Buddhism - The chief metaphysical concepts in Buddhism are...

- Translations of Buddhist texts by the Royal Asiatic Society - It has been a pure accident of circumstances...

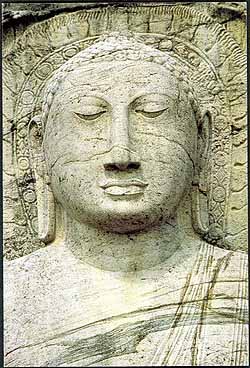

- The Buddha’s true face - In the Dhammadayada Sutta of the Majjhima Nikaya the Buddha says...

- The Buddha’s admonition to lay disciples - The Full Moon day of Medin (March). It commemorates mainly...

Some salient features of Buddhism

by Ven. Narada Thera

Courtesy: Buddhism in a nutshell

The foundations of Buddhism are the four Noble Truths - namely, Suffering (the raison d’etre of Buddhism), its cause, i.e. Craving, its end, i.e. Nibbana (the Summum Bonum of Buddhism), and the Middle Way.

What is the Noble Truth of Suffering ? "Birth is suffering, old age is suffering, disease is suffering, death is suffering, to be united with the unpleasant is suffering, to be separated from the pleasant is suffering, not to receive what one craves for is suffering, in brief the five Aggregates of Attachment are suffering.

What is the Noble Truth of the Cause of Suffering? "It is the craving which leads from rebirth to rebirth accompanied by lust of passion, which delights now here now there; it is the craving for sensual pleasures (Kamatanha), for existence (Bhavatanha) and for annihilation (Vibhava tanha)

What is the Noble Truth of the Annihilation of Suffering ? It is the remainderless, total annihilation of this very craving, the forsaking of it, the breaking loose, fleeing, deliverance from it.

What is the Noble Truth of the Path leading to the Annihilation of Suffering ? "It is the Noble Eightfold Path which consists of right understanding, right thoughts, right speech. right action, right livelihood, right endeavour, right mindfulness, and right concentration."

Whether the Buddhas arise or not these four Truths exist in the universe. The Buddhas only reveal these Truths which lay hidden in the dark abyss of time.

Scientifically interpreted, the Dhamma may be called the law of cause and effect. These two embrace the entire body of the Buddha’s Teachings.

The first three represent the philosophy of Buddhism; the fourth represents the ethics of Buddhism, based on that philosophy. All these four truths are dependent on this body itself. The Buddha states: - "In this very one-fathom long body along with perceptions and thoughts, do I proclaim the world, the origin of the world, the end of the world and the path leading to the end of the world" Here the term world is applied to suffering.

Buddhism rests on the pivot of sorrow. But it does not thereby follow that Buddhism is pessimistic. It is neither totally pessimistic no totally optimistic, but, on the contray, it teaches a truth that lies midway between them. One would be justified in calling the Buddha a pessimist if He had only enunciated the Truth of suffering without suggesting a means to put an end to it. The Buddha perceived the universality of sorrow and did prescribe a panacea for this universal sickness of humanity. The highest conceivable happiness, according to the Buddha, is Nibbana, which is the total extinction of suffering.

The author of the article on Pessimism in the Encyclopaedia Britannica writes: "Pessimism denotes an attitude of hopelessness towards life, a vague general opinion that pain and evil predominate in human affairs. The original doctrine of the Buddha is in fact as optimistic as any optimism of the West. To call it pessimism is merely to apply to it a characteristically Western principle to which happiness is impossible without personality. The true Buddhist looks forward with enthusiasm to absorption into eternal bliss."

Ordinarily the enjoyment of sensual pleasures is the highest and only happiness of the average man. There is no doubt a kind of momentary happiness in the anticipation, gratification and retrospection of such fleeting material pleasures, but they are illusive and temporary. According to the Buddha non-attachment is a greater bliss.

The Buddha does not expect His followers to be constantly pondering on suffering and lead a miserable unhappy life. He exhorts them to be always happy and cheerful for zest (Piti) is one of the factors of Enlightenment.

Real happiness is found within, and is not to be defined in terms of wealth, children, honours or fame. If such possessions are misdirected, forcibly or unjustly obtained, misappropriated or even viewed with attachment, they will be a source of pain and sorrow to the possessors.

Instead of trying to rationalise suffering,. Buddhism takes suffering for granted and seeks the cause to eradicate it. Suffering exists as long as there is craving. It can only be annihilated by treading the Noble Eightfold Path and attaining the supreme bliss of Nibbana.

These four Truths can be verified by experience. Hence the Buddha Dhamma is not based on the fear of the unknown, but is founded on the bedrock of facts which can be tested by ourselves and verified by experience. Buddhism is, therefore, rational and intensely practical.

Such a rational and practical system cannot contain mysteries or esoteric doctrines. Blind faith, therefore, is foreign to Buddhism. Where there is no blind faith there cannot be any coercion or persecution or fanaticism. To the unique credit of Buddhism it must be said that throughout its peaceful march of 2500 years no drop of blood was shed in the name of the Buddha, no mighty monarch wielded his powerful sword to propagate the Dhamma, and no conversion was made either by force or by repulsive methods. Yet, the Buddha was the first and the greatest missionary that lived on earth,

Aldous Huxley writes: - "Alone of all the great world religions Buddhism made its way without persecution censorship or inquisition."

Lord Russell remarks: - "Of the great religions of history, I prefer Buddhism, especially in its earliest forms; because it has had the smallest element of persecution."

In the name of Buddhism no altar was reddened with the blood of a Hypatia, no Bruno was burnt alive.

Buddhism appeals more to the intellect than to the emotion. It is concerned more with the character of the devotees than with their numerical strength.

On one occasion Upali, a follower of Nigantha Nataputta, approached the Buddha and was so pleased with the Buddha’s exposition of the Dhamma that he instantly expressed his desire to become a follower of the Buddha. But the Buddha cautioned him, saying:

"Of a verity, O householder, make a thorough investigation. It is well for a distinguished man like you to make (first) a thorough investigation."

Upali, who was overjoyed at this unexpected remark of the Buddha, said "Lord, had I been a follower of another religion, its adherents would have taken me round the streets in a procession proclaiming that such and such a millionaire had renounced his former faith and embraced theirs. But, Lord, Your Reverence advises me to investigate further. The more pleased am I with this remark of yours. For the second time, Lord, I seek refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and the Sangha."

Buddhism is saturated with this spirit of free enquiry and complete tolerance. It is the teaching of the open mind and the sympathetic heart, which, lighting and warming the whole universe with its twin rays of wisdom and compassion, sheds its genial glow on every being struggling in the ocean of birth and death.

The Buddha was so tolerant that He did not even exercise His power to give commandments to His lay followers. Instead of using the imperative, He said: - "It behoves you to do this - It behoves you not to do this." He commands not but does exhort.

This tolerance the Buddha extended to women and all living beings. It was the Buddha who first attempted to abolish slavery and vehemently protested against the degrading caste system which was firmly rooted in the soil of India. In the Word of The Buddha it is not by mere birth one becomes an outcast or a noble, but by one’s actions. Caste or colour does not preclude one from becoming a Buddhist or from entering the Order. Fishermen, scavengers, courtesans, together with warriors and Brahmins, were freely admitted to the Order and enjoyed equal privileges and were also given positions of rank. Upali, the barber for instance, was made in preference to all others the chief in matters pertaining to Vinaya discipline. The timid Sunita, the scavenger, who attained Arahatship was admitted by the Buddha Himself into the Order. Angulimala, the robber and criminal, was converted to a compassionate saint. The fierce Alavaka sought refuge in the Buddha and became a saint. The courtesan Ambapali entered the order and attained Arahatship. Such instances could easily be multiplied from the Tipitaka to show that the portals of Buddhism were wide open to all, irrespective of caste, colour or rank.

It was also the Buddha who raised the status of downtrodden women and not only brought them to a realization of their importance to society but also founded the first celibate religious order for women with rules and regulations.

The Buddha did not humiliate women, but only regarded them as feeble by nature. He saw the innate good of both men and women and assigned to them their due places in His teaching. Sex is no barrier to attaining Sainthood.

Sometimes the Pali term used to denote women is "Matugama" which means mother-folk or society of mothers. As a mother, woman holds an honourable place in Buddhism. Even the wife is regarded as "the best friend" (parama sakha) of the husband.

Hasty critics are only making ex-parte statements when they reproach Buddhism with being inimical to women. Although at first the Buddha refused to admit women into the Order on reasonable grounds, yet later He yielded to the entreaties of His foster-mother, Pajapati Gotami, and founded the Bhikkuni Order. Just as the Arahats Sariputta and Moggallana were made the two chief disciples in the Order of monks, even so He appointed Arahats Khema and Uppalavanna as the two chief female disciples. Many other female disciples too were named by the Buddha Himself as His distinguished and pious followers.

On one occasion the Buddha said to King Kosala who was displeased on hearing that a daughter was born to him:

"A woman child, O Lord of men; may prove Even a better offspring than a male."

Many women, who otherwise would have fallen into oblivion, distinguished themselves in various ways, and gained their emancipation by following the Dhamma and entering the Order. In this new Order, which later proved to be a great blessing to many women, queens, princesses, daughters of noble families, widows, bereaved mothers, destitute women, pitiable courtesans - all, despite their caste or rank, met on a common platform, enjoyed perfect consolation and peace, and breathed that free atmosphere which is denied to those cloistered in cottages and palatial mansions.

It was also the Buddha who banned the sacrifice of poor beasts and admonished His followers to extend their loving kindness (Metta) to all living beings - even to the tiniest creature that crawls at one’s feet. No man has the power or the right to destroy the life of another as life is precious to all.

A genuine Buddhist would exercise this loving-kindness towards every living being and identify himself with all, making no distinction whatsoever with regard to caste, colour or sex.

It is this Buddhist Metta that attempts to break all the barriers which separate one from another. There is no reason to keep aloof from others merely because they belong to another persuation or another nationality. In that noble Toleration Edict which is based on Culla-Vyuha and Maha-Vyuha Suttas, Asoka says: "Concourse alone is best, that is, all should hearken willingly to the doctrine professed by others."

Buddhism is not confined to any country or any particular nation. It is universal. It is not nationalism which, in other words, is another form of caste system founded on a wider basis. Buddhism, if it be permitted to say so, is super nationalism.

To a Buddhist there is no far or near, no enemy or foreigner, no renegade or untouchable, since universal love realised through understanding has established the brotherhood of all living beings. A real Buddhist is a citizen of the world. He regards the whole world as his motherland and all as his brothers and sisters.

Buddhism is, therefore, unique, mainly owing to its tolerance, non-aggressiveness, rationality, practicability, efficacy and universality. It is the noblest of all unifying influences and the only lever that can uplift the world.

These are some of the salient features of Buddhism, and amongst some of the fundamental doctrines may by said - Kamma or the Law of Moral Causation, the Doctrine of Rebirth, Anatta and Nibbana.

NIRVANA

By Dr. S. A. Ediriweera

Nirvana is a state of supreme happiness. It is life without suffering. It is the Third Noble Truth.

Nirvana is the ultimate aim of Buddhists. The summum bonum of Buddhism.

Nirvana is achieved in life and is not something gained after death. For example the Buddha attained Nirvana at the age of 35 years and lived till 80 years.

Nirvana is attained by completely eradicating craving and that could be done by following the Noble Eightfold Path (The Fourth Noble Truth).

Nirvana is absolute mental peace brought about by completely abolishing greed, hatred and delusion. Perfect mental peace is immense happiness, it is the happiness of calming down, tranquillity achieved by allaying passions.

Nirvana is not something to be perceived with the five senses. To a question by Udayi "What happiness can it be if there is no sensation"? Sariputta the chief disciple of the Buddha replied "That there is no sensation itself is happiness". Nirvana is a supramundane state to be realised by wisdom.

One who has achieved Nirvana is free from all forms of self identification. The concept of ‘self’ is no more. The Ego illusion is completely uprooted. Rebirth producing craving and ignorance has been stopped. The mind is not attached to anything, there is ceasing of becoming and one is delivered from all future rebirths and deaths.

Nirvana is not a place to enter into. Venerable Nagasena’s reply to King Milinda’s question "In what region is Nirvana located"? was "great king there is no place where Nirvana is located. Nevertheless this Nirvana exists. Just as there is no place where fire is located, the fact being that a man by rubbing two sticks together produces fire - so also there is such a thing as Nirvana, but no place where it is located. The fact being that a man by diligent mental effort realizes Nirvana."

Nirvana is complete inner transformation achieved by perfecting virtue and wisdom. Nirvana has to be experienced and cannot be expressed in words. One has to taste sugar to know its sweetness, words do not really convey the taste, similarly supreme bliss Nirvana has to be realized.

Just as there is Heat - there is Cold.

Just as there is Evil - there is Good.

Just as there is Darkness - there is Light.

Just as there is Dukkha - there is Nirvana.

With growing awareness, we strive,

To end the cycle of life and death,

Till a state we reach,

Where their is the end of sorrow.

Courtesy: Essentials of Buddhism

What should be the Vesak determination?

By Ven. Dr. P. Gnanarama Thera

Principal - Buddhist and Pali College of Singapore

The first Vesak of 21st Century dawns on May 7 in 2001. As the Buddhists all over the world know, Vesak is celebrated to commemorate the three major events of the Buddha's life: The Birth, the Enlightenment and the Parinibbana or the Final Passing Away of the Buddha.

Over forty-five years after his Enlightenment, he wandered from town to town, village to village in North India disseminating his message of compassion and wisdom. The high and the low, rich and the poor, fools and the wise, kings and commoners and the elite and the masses all alike, came under his net of compassion without any distinction whatsoever. It was a life dedicated to serve humanity. Sir Edwin Arnold in the Introduction to his classic "Light of Asia" observed three facets of the life of the Buddha blended into one. He stated. "He (the Buddha) combined the royal qualities of a prince with that of an intellect of a sage and the devotion of a martyr". It is with that stately personality, unique wisdom and unreserved compassionate dedication the Buddha stands before us, even twenty-five centuries after his earthly career.

Spread far and wide

While some of the belief systems struggled to survive and subsequently died down then and there, the message of the Buddha spread far and wide beyond the territorial boundaries of India across the world known at the time and recognised as a world religion. Its onward march is not smeared with blood or proselytizing zeal or persecution.

The missionaries armed only with compassion and good will carried the message of Dhamma across Asia and to the other parts of the Western Hemisphere known to them at the tune. Therefore the famous British philosopher Bertrand Russell remarked: "Of the great religions of history I prefer Buddhism, especially in its earliest forms, because it has had the smallest element of persecution." The self-same sentiment was expressed by Adams Beck, American traveller and author by saying that "it may well claim kindred with all the great faiths, persecuting and opposing none which differ with it, and this for reasons which are easily seen in the teachings themselves. In relation to this noble and scientific austerity no words are needed."

Pali Text Society

Within the last hundred and fifty years ancient Buddhist texts have been edited and translated into different languages. Pali Text Society established in London about a hundred years ago, is still continuing its avowed task of editing the texts together with English translations. Prof. Rhys Davids, the founder of the society was very much fascinated by studying Buddhism. For he remarked: "Buddhist or non-Buddhist, I have examined everyone of the great religious systems of the world, in none of them I have found anything to surpass, in beauty and comprehensiveness, the Noble Eight-fold Path and the Four Truths of the Buddha". Now, as these texts are freely available in many of the world languages, their rich content and depth of vision have attracted both Eastern and Western intellectuals of diverse disciplines. To name a few, there are eminent physicists, psychologists, psychoanalysts, philosophers, poets, physicalist, mathematicians, historians and social workers of our time among them.

What have been discussed by the Buddha are nothing but the problems perennially humankind is facing. Contemporary relevance of the Buddha's approach to them has been highly valued by many. Specially, eminent physicians and psychotherapists of our time have appreciated the technique of mind culture found in Buddhism. Dr. E. Graham Howe said: The more I studied Satipatthana, the more impressed I became with it as a system of mind training. It is in line with our Western scientific attitude of mind in that it is unprejudiced, objective and analytical. It relies on personal, direct experience, and not on anyone else's ideas or opinions. Dr. C. C Jung, the founder of the Jungian School of psychology explaining why he drew to the world of Buddhist thought said that the philosophy of the theory of evolution and the law of karma taught in Buddhism were far superior to any other creed. Continuing further he said: "My task was to treat psychic suffering and it was this that impelled me to become acquainted with the views and methods of that great teacher of humanity, whose principal theme was the chain of suffering, old age, sickness and death." So much so, William James, the American philosopher and psychologist declared: "I am ignorant of Buddhism, and speak under correction, and merely in order better to describe my general point of view; but as I apprehend the Buddhistic doctrine of karma, I agree in principle with that."

Alfred North Whitehead, the British mathematician and philosopher reviewing Buddhism through his philosophical standpoint proclaimed that "Buddhism is the colossal example in the history of applied metaphysics. " Another British philosopher, G D. Broad appreciating Buddhism as a way of life said: "The only one of the great religions which makes any appeal to me is Buddhism; and that, as I understand it, is rather a philosophy of the world, and a way of life founded upon it, than a religion in the ordinary sense of the word." Perhaps the German philosopher Frederich Nietzche is very forceful in expressing that "Buddhism is hundred times more realistic than other religions."

Out of conviction

Evidently, all of these appreciative remarks have been made out of conviction. As Buddhism had a past it will have a bright future too. They say history repeats itself. Colonizers and invaders tested the tolerance of Buddhists to the extent of their extinction. One African freedom fighter once remarked: "When whites came to our country they had the Bible, we had the lands, but now, we have the Bible, they have the lands." The trend is now changing. As Buddhism addresses to the problems of man rationally and scientifically, it has a wider appeal in the modern world. The eminent physicist of our time, Albert Einstein, therefore remarked: "If there is any religion that would cope up with scientific needs it would be Buddhism. " When the present century where conflict and confrontation, storm and strife have become the order of the day turning the world into a global village of battles, Buddhism has much to accomplish. Mahatma Gandhi, the apostle of non-violence therefore once remarked: "For Asia is not for Asia but for the whole world, it has to re-learn the message of the Buddba and deliver it to the whole world." At this juncture, we as Buddhists, we have a great responsibility before us. In this Vesak Day, therefore, let us determine to be equipped with a comprehensive knowledge of the Dhamma and practice it cultivating friendship and harmony, in order to fulfil the task before us.

Revolt against false values

By J.P. Pathirana

If you were to examine the values in which you have been nurtured from your childhood, you will realise most of them have been forced upon you by society; by the socio-economic and educational environment in which you had your early upbringing. On closer examination you will see that most of these values increase your life's tensions, anxieties and suffering rather than help resolve them.

This is because most of us ignore the basic truths and laws of life. Our social values today are sensate, false and changing. They do not touch reality.

The true Buddhist may revolt against these perishable, materialistic values that carry him farther from happiness and truth. He is expected to cultivate those imperishable and eternal values of the heart and mind which bring both harmony and individual peace.

Tragedy

Better cars, well equipped bathrooms, radios, televisions, films, hi-fi stereos etc., are expected to enhance human happiness. But the tragedy is that they have created new conditions of suffering. Better scientific discoveries mean more efficient methods of killing each other, more methodical and destructive wars, more deceptive methods of exploitation and so on. This situation dominates the technologically advanced West and has opened the eyes of many Westerners to the profound truths of life and the cosmos proclaimed by The Buddha.

Truths

The Buddhist has a two-fold duty; one toward himself, the other toward society. Where Buddhist truths conflict with the accepted values of society, he should be able to make a compromise instead of sacrificing his higher and nobler emotions for social expediency or shallow convention.

Society may place an absolute value on perishable things like money, power, wealth and property, name and fame. But the true Buddhist who understands the impermanence and therefore painful character of these changing, sensate material values, should break away from every false pattern of life.

Morals

Technology in itself is not an evil. But it is not the solution to our human problems, which are basically ethical and psychological, as the Buddha points out. It is because of the wrong emphasis laid on technology that external temporal values have taken precedence over ethical and moral values.

To the rulers of his day, the Buddha enunciated an excellent politico economic and social moral values. For example, the Five precepts (Panchasila) concept, is the most elementary expression of that value structure. If you examine human history, you will see that the most flourishing periods of human peace and happiness were those during which rulers were inspired by ethical codes and moral convictions. Think of the long reign of Asoka the Great or even Charlemagne. Think of the long line of Sinhalese Kings (from Devanampiyatissa to Mahasena) who embraced Buddhism and disseminated Buddhist ideals in ancient Sinhalese society.

Conversely, the dark periods in human history were those in which rulers sacrificed the nobler emotions of the heart and mind and tried to assert their brutal instincts of hatred and jealousy, revenge and self aggression like Napoleon, Hitler and Mussolini. Think of the colossal destruction of life and property they have been responsible for.The tendency to defy truth and justice has its roots in ignorance of the Buddha Dhamma. Many nations today are unaware of the obvious truth that mere socio-economic development does not solve a country's problems.

Put the Dhamma into practice and vividly see the beneficial results and the solace and peace that will follow in its trail.

Path to mindfulness

Yet another issue of 'Vesak Lipi', the colourful bilingual Buddhist Digest has come out well in time for this year's Vesak. It is one of the few Vesak annuals which has maintained an unbroken record of continuous publication. This year's is the 17th issue and editor/compiler Upali Salgado has once again given us plenty of reading matter with a fine collection of Sinhala and English articles.

The search for meaningful articles had made the editor browse through earlier published material by well known writers. Bhikkhu Kassapa, for instance, discusses 'What are we - and whither bound?', questions which have troubled thinkers of all ages. "Just as a chemist confronted with a crystal of sodium-chloride will say 'this is sodium-chloride," and will assume nothing more about that crystal beyond what he can test and demonstrate, the Buddha says -'this man, this animal, is matter ('rupa') and mind ('nama'). There is nothing more, nothing less to him than just that, mind and matter ('nama-rupa'). Mind is put first because it is all important," he explains.

Incidentally, many may not remember that it was Bhikkhu Kassapa (formerly Dr. Cassius A. Pereira) who founded 'The Servants of the Buddha' on April 16,1921.

Presenting the 'Importance of Mindfulness', Ven. Piyadassi explains how right mindfulness helps us sharpen powers of observation and assists right thinking and understanding. Orderly thinking and reflection is conditioned by man's right mindfulness or awareness. It is instrumental not only in bringing concentrative calm but in promoting right living. It is an essential factor in all our actions both worldly and spiritual.

Ven. Narada's 'What is it that is reborn?' is among several articles on 'Death and to the other side'. This series includes 'Reflection on death' by Ven. Weragoda Saradha, 'The only way to have a good death' by E. M. G. Edirisinghe, 'Those terrifying ghosts' by Egerton Baptist, 'Facing death with a smile' by Raja Kuruppu and short story titled 'The gallows' by Dr. R. L. Soni. A good editing job has been done to present what originally would have been long articles to concise ones.

Ven. Dr. K. Sri Dhammananda in an article titled 'The Noble Path to Follow', while explaining the four Noble Truths highlights the dangers of craving. The writer describes craving as "a fire which burns in all beings" and says that every activity is motivated by desire.

"They range from the simple physical desire of animals to the complex and often artificially stimulated desires of the civilized man. To satisfy desire, animals may prey upon one another, and human beings fight, kill, cheat, lie and perform various forms of unwholesome deeds.

Craving is a powerful mental force present in all forms of life and is the chief cause of the ills in life. It is craving that leads to repeated births in the cycle of existence".

With increasing interest in meditation, 'Vesak Lipi' carries a list of some better known meditation centres in Sri Lanka. A pictorial feature in colour introduces the reader to one such place - Kanduboda, 'where monks paddle their own canoe to freedom'. This is a feature that should be continued in each issue.

Working through the year, editor Salgado plans the publication well ahead of Vesak and keeps on improving both its contents and presentation every year. More colour pages, beautifully printed by Softwave Printing & Packaging adorn the current issue. The cover features the Buddha as seen at the Mulagandhikuta Vihare, Saranath, where the Buddha preached His first sermon.

As the book is opened, the reader is treated to a very artistic old Burmese painting, also in colour, depicting the birth of Prince Siddhartha in the Sal grove at Lumbini.

It is encouraging to see that donors continue to support 'Vesak Lipi' which has a readership in over 20 countries in the world. It is distributed free and is sent to nearly 400 school and public libraries throughout the country.

"Let the Dhamma be your refuge"

By Upali Salgado

The birth of a child brings joy to his parents. But one who is appreciative of Theravada Buddhist philosophy looks at such an event, as being inevitable; yet another happening in one's samsaric journey. When the baby saw the light of this world, little did he realize there was suffering everywhere.

The mission of Sakyamuni Gothama Buddha was to be "awakened", to the truth relating to Dukkha (pain, anguish, disappointment, and suffering). His mission, as a teacher, was to "show the way" to end all forms of suffering.

Prince Siddhartha was born in 623 BC at the Sal grove in Lumbini, Nepal. Though of royal birth, certain marks on his body seen at birth, and his behaviour destined him to be a sage and a Buddha. The Buddha did not believe in or tell us of a creator God, nor was he a divine Messiah. He was not a Vaidika or follower of Vedic Brahminism. He was an extraordinary man born "to give light" to suffering humanity, at a time when there were 63 other religious leaders in India all professing shades of orthodox Hinduism or Jainism.

The Buddha's Theravada Dhamma (philosophy) was not only a reaction to ritualism but also against adherence to the caste system. In fact, two of his foremost disciples Upali of the barber caste and Sumedha who was a scavenger were of lower social status. Women who were in shackles were liberated in status and permitted to be nuns.

He emphasised the need to follow Ahimsa and advocated religious tolerance of other faiths. The cardinal axis of his Dhamma wheel, was the identification of the noble truth relating to the cause of Dukkha and how to end Dukkha (suffering); Annichya (impermanence of everything known to man) and Anathma (absence of one's soul). Gotama Buddha did not speak of repentance or condemn man as a sinner. The concept of sin had no place in his teachings.

As a Bodhisatva, Prince Siddhartha mastered ten perfections of keeping the precepts, wisdom, courage, patience, freedom from attachment, goodwill, indifference, endurance, alms giving or sacrifice in its extreme forms (as seen in the Vessanthara, Sivi and Sasa Jathaka stories),and to have the strength to know the Truth (as an Awakened One) - the Buddha. He was the embodiment of Maha Karuna (or great compassion for all living creatures and humans) and spoke in the language of the people he lived with. He did not rely on miracles to propogate his Dhamma, although he did perform a single miracle before the Jain leader Mahaveera, to show that he was the "All Knowing One" - a Buddha.

What Nehru said....

Jawaharlal Nehru, in his celebrated book "Discovery of India" wrote, "The Buddha.... seated on a lotus flower, calm and impassive, above passion and desire, beyond the storm and strife of this world, so far, far away. He seems out of reach, unattainable. Yet, again as we look behind those still, unmoving features, there is a passion and an emotion strange and more powerful than the passions and emotions we have known. His eyes are closed, but some power of spirit looks out of them, and a vital energy fills the frame."

Before the Buddha Jayanthi celebrations, when the Government of India moved in the Lok Sabha, a massive vote of several million rupees, to renovate and preserve several Buddhist Vihares and monuments at Buddha Gaya, at Saranath, Jetawane Monastery and Sanchi Vihares and at Kushinara (where he passed away), a member of the Lok Sabha asked why India should be concerned to spend money for the "glorification of a religion that has adherents less than 5% of her population." Prime Minister Nehru, replied in just three sentences: "We, and the world today consider India's greatest son was Sakyamuni Gothama Buddha. He gave "light" not only to India with his deep thoughts of compassion, but also to the whole world. We are truly proud of this great teacher and sage."

Dr. Rajendra Prasad, President, also said, "It is characteristic of Gotama Buddha's message to mankind that, with the passage of time, far from becoming obsolete, it shines today like a beacon light.

His Dhamma

Prince Siddhartha, the Buddha to be, was born on a full moon day (Poya) in May, in an open Sal grove. In 1885, Dr. Fuhrer, a German archaeologist discovered a massive pillar erected by Emperor Dhamma-Asoka, who visited Lumbini in 250 BC, to pay homage to the birthplace of Prince Siddhartha. The pillar bears the following inscription: "Deva Piyana Piyadassina Buddha Jate Sakyamuni Bhagavan, Lumbini Game Ubalike Kate". The English translation: "King Piyadassi beloved of the Gods having been anointed (king) 20 years came himself and worshipped saying, here Buddha Sayamuni was born." .... The inscription also says: "Because the worshipful one was born here, this village Lumbini will be free of taxes and will receive wealth".

Prince Siddhartha gained Enlightenment at Buddha Gaya again when seated in the open under a bo-tree, on a Poya full moon day in May. He sat there meditating and when in a deep Jhana realized the noble truth of suffering, and the way to end suffering. To quote Aggha Maha Panditha Venerable Walpola Rahula (author of What the Buddha Taught), according to the Buddha Dhamma, the idea of self is imaginary, false belief which has no corresponding reality, and it produces harmful thoughts of "Me" and "Mine", selfish desire, craving, attachment, hatred, ill-will, conceit, pride, egoism and other defilements and problems. The Buddha Dhamma teaches that it is the source of all trouble or suffering or pain in the world, from personal conflicts to wars between nations.

Ven. Walpola continues, "Two ideas are psychologically deep rooted in man, self protection and self preservation. For self protection (fear) man has created God in which he depends for his own protection, safety and security. For self preservation, man has conceived the idea of an immortal Soul or "Athma" which live eternally. In his ignorance, weakness and fear and desire, man needs two things to console himself. Hence he clings to them fanatically. The Buddha Dhamma does not support ignorance, weakness, fear, desire".

To make that statement clear Buddhists believe that ignorance which is the root of suffering depends on intentional activity. On intentional activity depends name and form. On name and form depends the six organs of sense. On the six organs of sense (smell, taste, etc) depend sensations. On sensations depend clinging or desire or craving. On craving depends attachment. On attachment depends existence or karma (one's actions or volition; good or bad). On existence depends, birth, old age and death (Jathi, Jara, Marana).

Therefore, to end the "Me" or "Self" one must make a personal effort. The Vissudhi Magga (XIX) says: "No Deva, no Brahma can be called the maker of this "Wheel of Life". Empty phenomena roll on, dependent on conditions all". Dhana, Seela and Bhavana is the prescription to achieve this by oneself. No God or force above can help you.

The Buddha said: "Be ye islands unto yourselves, be ye a refuge to yourselves. Take no other refuge. Let the Dhamma be your island, the Dhamma be your refuge".

An Udana saying:

"Self alone is Lord self,

What higher Master can there be?

By self alone, is evil done,

By self alone, is one defiled...."

Sunday Times - 6 May 2001

The significance of Vesak

By Venerable Mahinda

The significance of Vesak lies with the Buddha and his universal peace message to mankind.

As we recall the Buddha and his Enlightenment, we are immediately reminded of the unique and most profound knowledge and insight which arose in him on the night of his Enlightenment. This coincided with three important events which took place, corresponding to the three watches or periods of the night.

During the first watch of the night, when his mind was calm, clear and purified, light arose in him, knowledge and insight arose. He saw his previous lives, at first one, then two, three up to five, then multiples of them... ten, twenty, thirty to fifty. Then 100, 1000 and so on.... As he went on with his practice, during the second watch of the night, he saw how beings die and are reborn, depending on their Karma, how they disappear and reappear from one form to another, from one plane of existence to another. Then during the final watch of the night, he saw the arising and cessation of all phenomena, mental and physical. He saw how things arose dependent on causes and conditions. This led him to perceive the arising and cessation of suffering and all forms of unsatisfactoriness paving the way for the eradication of all taints of cravings. With the complete cessation of craving, his mind was completely liberated. He attained to Full Enlightenment. The realisation dawned in him together with all psychic powers.

This wisdom and light that flashed and radiated under the historic Bodhi Tree at Buddha Gaya in the district of Bihar in Northern India, more than 2500 years ago, is of great significance to human destiny. It illuminated the way by which mankind could cross, from a world of superstition, or hatred and fear, to a new world of light, of true love and happiness.

The heart of the Teachings of the Buddha is contained in the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, namely,

The Noble Truth of Dukkha or suffering

The Origin or Cause of suffering

The End or Cessation of suffering

the Path which leads to the cessation of all sufferings

The First Noble Truth is the Truth of Dukkha which has been generally translated as ‘suffering’.

But the term Dukkha, which represents the Buddha’s view of life and the world, has a deeper philosophical meaning. Birth, old age, sickness and death are universal. All beings are subject to this unsatisfactoriness. Separation from beloved ones and pleasant conditions, association with unpleasant persons and conditions, and not getting what one desires - these are also sources of suffering and unsatisfactoriness. The Buddha summarises Dukkha in what is known as the Five Grasping Aggregates.

Herein, lies the deeper philosophical meaning of Dukkha for it encompasses the whole state of being or existence.

Our life or the whole process of living is seen as a flux of energy comprising of the Five aggregates, namely the Aggregate of Form or the Physical process, Feeling, Perception, Mental Formation, and Consciousness. These are usually classified as mental and physical processes, which are constantly in a state of flux or change.

When we train our minds to observe the functioning of mental and physical processes we will realise the true nature of our lives. We will see how it is subject to change and unsatisfactoriness.

And as such, there is no real substance or entity or Self which we can cling to as ‘I’, ‘my’ or ‘mine’.

When we become aware of the unsatisfactory nature of life, we would naturally want to get out from such a state. It is at this point that we begin to seriously question ourselves about the meaning and purpose of life. This will lead us to seek the Truth with regards to the true nature of existence and the knowledge to overcome unsatisfactoriness.

From the Buddhist point of view, therefore, the purpose of life is to put an end to suffering and all other forms of unsatisfactoriness - to realise peace and real happiness. Such is the significance of the understanding and the realisation of the First Noble Truth.

The Second Noble Truth explains the Origin or Cause of suffering. Tanha or craving is the universal cause of suffering. It includes not only desire for sensual pleasures, wealth and power, but also attachment to ideas, views, opinions, concepts, and beliefs. It is the lust for flesh, the lust for continued existence (or eternalism) in the sensual realms of existence, as well as the realms of form and the formless realms. And there is also the lust and craving for non-existence (or nihilism). These are all different Forms of selfishness, desiring things for oneself, even at the expense of others.

Not realizing the true nature of one’s Self, one clings to things which are impermanent, changeable and perishable. The failure to satisfy one’s desires through these things; causes disappointment and suffering.

Craving is a powerful mental force present in all of us. It is the root cause of our sufferings. It is this craving which binds us in Samsara - the repeated cycle of birth and death.

The Third Noble Truth points to the cessation of suffering. Where there is no craving, there is no becoming, no rebirth. Where there is no rebirth, there is no decay. No, old age, no death, hence no suffering. That is how suffering is ended, once and for all.

The Fourth Noble Truth explains the Path or the Way which leads to the cessation of suffering. It is called the Noble Eightfold Path.

The Noble Eightfold path avoids the extremes of self-indulgence on one hand and self-torture on the other. It consists of Right Understanding, Right Thought, Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness and Right Concentration.

These path factors may be summarised into 3 stages of training, involving morality, mental culture and wisdom.

Morality or good conduct is the avoidance of evil or unwholesome actions &emdash; actions which are tainted by greed, hatred and delusion; and the performance of the good or wholesome actions, - actions which are free from greed, hatred and delusion, but motivated by liberality, loving-kindness and wisdom.

The function of good conduct or moral restraint is to free one’s mind from remorse (or guilty conscience). The mind that is free from remorse (or guilt) is naturally calm and tranquil, and ready for concentration with awareness.

The concentrated and cultured mind is a contemplative and analytical mind. It is capable of seeing cause and effect, and the true nature of existence, thus paving the way for wisdom and insight.

Wisdom in the Buddhist context, is the realisation of the fundamental truths of life, basically the Four Noble Truths. The understanding of the Four Noble Truths provide us with a proper sense of purpose and direction in life. They form the basis of problem-solving.

The message of the Buddha stands today as unaffected by time and the expansion of knowledge as when they were first enunciated.

No matter to what lengths increased scientific knowledge can extend man’s mental horizon, there is room for the acceptance and assimilation for further discovery within the framework of the teachings of the Buddha.

The teaching of the Buddha is open to all to see and judge for themselves. The universality of the teachings of the Buddha has led one of the world’s greatest scientists, Albert Einstein to declare that ‘if there is any religion that could cope with modern scientific needs, it would be Buddhism’.

The teaching of the Buddha became a great civilising force wherever it went. It appeals to reason and freedom of thought, recognising the dignity and potentiality of the human mind. It calls for equality, fraternity and understanding, exhorting its followers to avoid evil, to do good and to purify their minds.

Realising the transient nature of life and all worldly phenomena, the Buddha has advised us to work out our deliverance with heedfulness, as ‘heedfulness is the path to the deathless’.

His clear and profound teachings on the cultivation of heedfulness otherwise known as Satipatthana or the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, is the path for the purification of beings - for the overcoming of sorrows and lamentation, for the destruction of all mental and physical sufferings, for the attainment of insight and knowledge and for the realisation of Nibbana. This has been verified by his disciples. It is therefore a path, a technique which may be verified by all irrespective of caste, colour or creed.

The Bodhi-Puja

The veneration of the Bodhi-tree (pipal tree: ficus religiosa) has been a popular and a widespread ritual in Sri Lanka from the time a sapling of the original Bodhi-tree at Buddhagaya (under which the Buddha attained Enlightenment) was brought from India by the Theri Sanghamitta and planted at Anuradhapura during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa in the third century B.C. Since then a Bodhi-tree has become a necessary feature of every Buddhist temple in the island.

The ritualistic worship of trees as abodes of tree deities (rukkhadevata) was widely prevalent in ancient India even before the advent of Buddhism. This is exemplified by the well-known case of Sujata’s offering of milk-rice to the Bodhisatta, who was seated under a banyan tree on the eve of his Enlightenment, in the belief that he was the deity living in that tree. By making offerings to these deities inhabiting trees the devotees expect various forms of help from them. The practice was prevalent in pre-Buddhist Sri Lanka as well. According to the Mahavamsa, King Pandukabhaya (4th century B.C.) fixed a banyan tree near the western gate of Anuradhapura as the abode of Vessavana, the god of wealth and the regent of the North as well as the king of the yakkhas. The same king set apart a palmyra palm as the abode of vyadha-deva, the god of the hunt (Mhv. x,89, 90).

After the introduction of the Bodhi-tree, this cult took a new turn. While the old practice was not totally abandoned, pride of place was accorded to the worship of the pipal tree, which had become sacred to the Buddhists as the tree under which Gotama Buddha attained Enlightenment. Thus there is a difference between the worship of the Bodhi-tree and that of other trees. To the Buddhists, the Bodhi-tree became a sacred object belonging to the paribhogika group of the threefold division of sacred monuments, while the ordinary veneration of trees, which also exists side-by-side with the former in Sri Lanka, is based on the belief already mentioned, i.e. that there are spirits inhabiting these trees and that they can help people in exchange for offerings. The Buddhists also have come to believe that powerful Buddhist deities inhabit even the Bodhi-trees that receive worship in the purely Buddhist sense. Hence it becomes clear that the reverence shown to a tree is not addressed to the tree itself. However, it also has to be noted that the Bodhi-tree received veneration in India even before it assumed this Buddhist significance; this practice must have been based on the general principle of tree worship mentioned above.

Once the tree assumed Buddhist significance its sanctity became particularized, while the deities inhabiting it also became associated with Buddhism in some form. At the same time, the tree became a symbol representing the Buddha as well. This symbolism was confirmed by the Buddha himself when he recommended the planting of the Ananda Bodhi-tree at Jetavana for worship and offerings during his absence (see J.iv,228f.). Further, the place where the Buddha attained Enlightenment is mentioned by the Buddha as one of the four places of pilgrimage that should cause serene joy in the minds of the faithful (D.ii,140). As Ananda Coomaraswamy points out, every Buddhist temple and monastery in India once had its Bodhi-tree and flower altar as is now the case in Sri Lanka.

King Devanampiya Tissa, the first Buddhist King of Sri Lanka, is said to have bestowed the whole country upon the Bodhi-tree and held a magnificent festival after planting it with great ceremony. The entire country was decorated for the occasion. The Mahavamsa refers to similar ceremonies held by his successors as well. It is said that the rulers of Sri Lanka performed ceremonies in the tree’s honour in every twelfth year of their reign (Mhv. xxxviii,57).

King Dutugemunu (2nd century B.C.) performed such a ceremony at a cost of 100,000 pieces of money (Mhv. xxviii,]). King Bhatika Abhaya (1st century A.C.) held a ceremony of watering the sacred tree, which seems to have been one of many such special pujas. Other kings too, according to the Mahavamsa, expressed their devotion to the Bodhi-tree in various ways (see e.g. Mhv. xxxv, 30; xxxvi, 25, 52, 126).

It is recorded that forty Bodhi-saplings that grew from the seeds of the original Bodhi-tree at Anuradhapura were planted at various places in the island during the time of Devanampiya Tissa himself. The local Buddhists saw to it that every monastery in the island had its own Bodhi-tree, and today the tree has become a familiar sight, all derived, most probably, from the original tree at Anuradhapura through seeds. However, it may be added here that the notion that all the Bodhi-trees in the island are derived from the original tree is only an assumption. The existence of the tree prior to its introduction by the Theri Sanghamitta cannot be proved or disproved.

The ceremony of worshipping this sacred tree, first begun by King Devanampiya Tissa and followed by his successors with unflagging interest, has continued up to the present day. The ceremony is still as popular and meaningful as at the beginning. It is natural that this should be so, for the veneration of the tree fulfils the emotional and devotional needs of the pious heart in the same way as does the veneration of the Buddha-image and, to a lesser extent, of the dagaba. Moreover, its association with deities dedicated to the cause of Buddhism, who can also aid pious worshippers in their mundane affairs, contributes to the popularity and vitality of Bodhi-worship.

The main centre of devotion in Sri Lanka today is, of course, the ancient tree at Anuradhapura, which, in addition to its religious significance, has an historical importance as well. As the oldest historical tree in the world, it has survived for over 2,200 years, even when the city of Anuradhapura was devastated by foreign enemies. Today it is one of the most sacred and popular places of pilgrimage in the island. The tree itself is very well guarded, the most recent protection being a gold-plated railing around the base (ranvata). Ordinarily, pilgrims are not allowed to go near the foot of the tree in the upper terrace. They have to worship and make their offerings on altars provided on the lower terrace so that no damage is done to the tree by the multitude that throng there. The place is closely guarded by those entrusted with its upkeep and protection, while the daily rituals of cleaning the place, watering the tree, making offerings, etc., are performed by bhikkbus and laymen entrusted with the work. The performance of these rituals is regarded as of great merit and they are performed on a lesser scale at other important Bodhi-trees in the island as well.

Thus this tree today receives worship and respect as a symbol of the Buddha himself, a tradition which, as stated earlier, could be traced back to the Ananda Bodhi-tree at Jetavana of the Buddha’s own time. The Vibhanga Commentary (p.349) says that the bikkhu who enters the courtyard of the Bodhi-tree should venerate the tree behaving with all humility as if he were in the presence of the Buddha. Thus one of the main items of the daily ritual at the Anuradhapura Bodhi-tree (and at many other places) is the offering of alms as if unto the Buddha himself. A special ritual held annually at the shrine of the Anuradhapura tree is the hanging of gold ornaments on the tree. Pious devotees offer valuables, money and various other articles during the performance of this ritual.

Another popular ritual connected with the Bodhi-tree is the lighting of coconut-oil lamps as an offering (pahan- puja), especially to avert the evil influence of inauspicious planetary conjunctions. When a person passes through a troublesome period in life he may get his horoscope read by an astrologer in order to discover whether he is under bad planetary influences. If so, one of the recommendations would invariably be a bodhi-puja, one important item of which would be the lighting of a specific number of coconut-oil lamps around a Bodhi-tree in a temple. The other aspects of this ritual consist of the offering of flowers, milk-rice, fruits, betel, medicinal oils, camphor, and coins. These coins (designated panduru) are washed in saffron water and separated for offering in this manner. The offering of coins as an act of merit-acquisition has assumed ritualistic significance with the Buddhists of the island. Every temple has a charity box (pin-pettiya) into which the devotees drop a few coins as a contribution for the maintenance of the monks and the monastery. Offerings at devalayas should inevitably be accompanied by such a gift. At many wayside shrines there is provision for the offering of panduru and travellers en route, in the hope of a safe and successful journey, rarely fail to make their contribution. While the coins are put into the charity box, all the other offerings would be arranged methodically on an altar near the tree and the appropriate stanzas that make the offering valid are recited. Another part of the ritual is the hanging of flags on the branches of the tree in the expectation of getting one’s wishes fulfilled.

Bathing the tree with scented water is also a necessary part of the ritual. So is the burning of incense, camphor, etc. Once all these offerings have been completed, the performers would circumambulate the tree once or thrice reciting an appropriate stanza. The commonest of such stanzas is as follows:

Yassa mule nisinno va

sabbari vijayam aka

patto sabbannutam Sattha

Vande tam bodhipadapam.

Ime ete mahabodhi

lokanathena pujita

ahampi te namassami

bodhi raja namatthu te.

"I worship this Bodhi-tree seated under which the Teacher attained omniscience by overcoming all enemical forces (both subjective and objective). I too worship this great Bodhi-tree which was honoured by the Leader of the World. My homage to thee, O King Bodhi."

The ritual is concluded by the usual transference of merit to the deities that protect the Buddha’s Dispensation.

Source: Buddhist Ceremonies and Rituals of Sri Lanka by A. G. S. Kariyawasam

What did the Lord Buddha teach?

"Just as darkness is removed by light, ignorance is removed or destroyed by wisdom, insight or the realization of what we really are. For this purpose we have each to make a deep search for ourselves"

A talk given at London Vihara on 26th May 1986

by Ven. Blalangoda Anandamaitreya

The only person who could answer the question "What did the Lord Buddha teach?" was nobody else but the Buddha himself. Let us see what his answer would be.

One day when the Lord Buddha was staying in the Simsapa forest near Madhura, he picked up a few leaves, and holding them up in his hand, he asked his disciples, "What, bretheren, are more numerous, either the leaves in my hand or those in this vast forest?" They said. "Lord, what you hold in your hand are but few leaves. But the leaves in this vast forest are uncountably more numerous".

Then the Lord Buddha rejoined, "In exactly the same way, bretheren, what I teach you ever, now as before, are but very few things out of what I know, and what I teach you are the Dukkha and the cessation of Dukkha.

Why did he want to spealc only of these two? It is because only the knowledge of these two things deals with the removal and cessation of all suffering or miseries of one’s life. Here Dukkha or suffering and unsatisfactoriness refer to the unhappy side of life and the cause of its arising and continuity. The cessation of dukkha refers to the attainment of real peace and the way thereto. These four facts are called the Four Great Truths, the description of which is called Buddhism in modern terminology.

The whole purpose of the Lord Buddha was to make his hearers realize these four great facts, He explained these truths in various ways suiting different levels of intelligence of his hearers.

The first of the four facts is suffering and the unsatisfactory nature of the existence which we call world. Wherever we look we see change at every moment with its varied aspects such as birth, decay, pain, sorrow, suffering, diseases, union with the disagreeable, disunion from the agreeable, depression, despair and death. Every living being, from the moment of his birth, goes on uninterruptedly towards death. This life in the world implies a journey towards death. His living or life means his continued or incessant journey towards death. Thus life in the world implies a journey to death, the most disagreeable event, and birth implies the start, the setting out of this pre destined journey. Thus, birth in any place where there is death or falling away from the present state is unsatisfactory, in its entirety, let alone its other aspects, decay, disease and the like. The increase in the number of rebirths means the increase of the number of deaths and all other unsatisfactory states.

Why and how does this unsatisfactoriness continue? Beings do not see where they are and what they are. Because of this not seeing, because of this spiritual blindness or ignorance, they are attached to, crave for this unsatisfactory existence, mistaking its deceiving guises for happiness. This craving or attachment is the most powerful force that drags back the beings to be reborn over and over again even when their physical frame falls lifeless. This attachment is the real Satan that is busily working in every worldling.

The truth concerning this attachment is the second one of the four great facts.

If there is disease there is its opposite in health. Heat has its opposite in coolness. Darkness has its opposite in light. In the same way if there is unsatisfactoriness inthe forms of decay, desease and so on, there must be its direct opposite state in the form of eternal bliss or everlasting peace, which is the cessation of unsatisfactory existence. The truth concerning this fact is the third one among the four great truths.

The attachment to this unsatisfactory existence is due to ignorance, the absence of realization of the exact nature of this existence. If the same ignorance is rooted out, then attachment the upshot of ignorance finds no ground to arise in.

Just as darkness is removed by light, ignorance is removed or destroyed by wisdom, insight or the realization of what we really are. For this purpose we have each to make a deep search for ourselves.

Nothing can be successfully done by one who has no self control. One must have control over one’s speech and deed. Then one should control one’s mind by keeping it from straying. Next to this, one must start one’s search of oneself. This process of practice begins at verbal and bodily control which is named as Sila or virtue or right conduct in Buddhist terminology. Depending on Sila (verbal and bodily discipline) one has to develop mind control, which is termed Samadhi or one pointedness of mind. Depending on this, one must start the search of oneself, the self-investigation, which is called the Vipassana in Buddhist terminology.

This is the three-factored discipline, which is otherwise called the eight-factored path in another way of classification.

The factors of the path are: - Right understanding, Right thought, Right speech, Right action, Right livelihood, Right endeavour, Right mindfulness and Right concentration. Out of these eight factors Right speech, Right action and Right livelihood form the factor of Sila or good conduct, in other words, moral discipline.

Right effort, Right mindfulness and Right concentration-these three together form the factor Samadhi or Concentration. Right understanding and Right thought&emdash;these two together form the factor of Panna or Insight. This threefactored discipline or eight-factored path is the way that leads to eternal peace by destroying the cause of the unsatisfactory existence. This is the last one of the four great truths.

Thus the exposition of these four great Truths is what we call Buddhism, the teaching of the Lord Buddha.

One may ask why the Buddha was not interested in dealing with the questions about the origin of the universe and the like.

Suppose there is a doctor or a physician in charge of a sick ward. He has to attend every patient in the sick ward. Some patients are so ignorant that they eat and drink things which make their diseases serious or incurable. So the physician has to make them understand their situation, Accordingly, he explains to diseases. He explains to rise and continuity of to them that they can hopeful and encourages he gives the treatment. Thus, to explain the nature of their diseases, their cause, that they can be cured and the treatment &emdash; these four facts are the only things the patients have to deal with. So the physician deals only with these four things and doesn’t listen to their questions about the things astronomical, geographrcal, geological and the like which have nothing to do with their diseases or their cure.

The Lord Buddha was the physician or healer of our inner diseases such as greediness, hatred, jealousy and the like which make us suffer from all sorts of afflictions. The cause of all these mental diseases is our own ignorance as to our present nature. So he, as our healer, regarded it his duty and service to teach us and make us realize only the Four Great Truths, and did not interfere with other problems which have nothing to do with the freedom from our imperfect and unsatisfactory state.

Meditation On Mindfulness

A Talk at Vedanta Centre Santa Barbara California on July 19, 1986

First of all I must thank Swamiji and the Vedanta nuns for inviting me to give a talk on this important occasion. The talk will be on ‘`Meditation (on Mindfulness)" in practice. I will try to explain, from Buddhist point of view, mindfulness and its development.

When we think of mindfulness, first of all we must understand what unmindfulness is. There are so many things which are on the opposite side of mindfulness: lack of attention, carelessness absent- mindedness, forgetfulness, negligence and neglect. So, in this way we have to understand the harm that unmindfulness might bring to us, to our spiritual life as well, as to our daily life. From this way we can understand, little by little, the value of mindfulness.

For example, suppose there is some dirt in a dark corner of a house. The householder doesn’t care because, at first, there is very little dirt in that dark nook. Every day, gradually some more debris collects there. Even though sometimes he goes to that side of the house and sees the dirt, he-thinks, ‘’Oh, this is very little. Some other day I will clear it up". But he doesn’t do anything about it. He attends to other works instead. Day by day this dirt collects. After some months, when he sees that it is a heap of dirt, he then begins to think that it would be very difficult to remove it all at once. "I will get somebody to remove it some day.’

A year passes. What happens? Suddenly the members of the house feel a little sick. Some strong odor comes from somewhere, but they are not so attentive to know from where it comes. So after awhile they get sick and have to see a doctor and receive treatment. For the time being, they get better. But again they get sick. They don’t know why, because they simply can’t find out the reason for the sickness. However, the thorough doctor discovers the cause of all the trouble: the heap of dirt has become a cradle of mosquitoes, cockroaches, and other harmful insects. Thus, at last they have to remove the whole amount of refuse. However, it is very difficult because there are many layers, due to the age of the debris. After it is removed and that part of the house is cleaned, all ill&emdash;health disappears.

That is the nature of carelessness: it becomes a cause of so much harm and danger, even to the body. Similarly, it is the case with our lives. Just as unmindfulness, with regard to our external environment, can bring us trouble, so ‘It’ is unmindfulness that can create serious problems in business affairs and trade, as well as in the affairs of state. However, unmindfulness plays still greater havoc with our inner life, if we are not cautious. ``The failure to achieve full knowledge of one’s own nature is the worst and greatest loss," said the Lord Buddha. In this connection, I will explain how the neglect of even a slight defect can bring great harm to oneself.

Sometimes a person may carelessly seek a fight. For fun he pretends to be rough. At the start it is fun and playfulness but later it becomes a habit. In short, he turns into a quarrelsome person. He doesn’t care. ‘’These are simple things," he may think. But, due to negligence, his behaviour becomes a habit. As habits leave some impressions in the dark nook of the mind, these impressions, lying dormant, cannot be rooted out, because he is not attentive. Instead, they grow slowly and develop into hindrances to spiritual development. They may also develop to such an extent that they become the source of crimes and acts of aggression.

Again, sometimes one may see a beautiful person of the Opposite sex, and feel some kindness. He understands that he has a kind or loving feeling towards that person. Of course, love, kindness, and unselfishness are virtues. And this kindness brings both people together as friends to help each other in need. Kindness is a very good thing. But, little by little, due to carelessness this kindness, or love, may turn into lust. At the start it appears to be a virture very good quality of his heart. But due to unmindfulness, it turns to lust one day and impels them to live an immoral life together.

Sometimes a person may dislike a wayward person. He is not angry with him, but he doesn’t like the other person’s evil ways. This dislike for wayward people or their bad deeds is good, but if he is not mindful enough, gradually he will begin to get angry. At last there may arise within his heart some sort of hatred. Thus he may develop into a hot-tempered person. Dislike for bad people is good, but hatred or anger is not. One should not be angry with anybody &emdash; even for a wrong deed. Thus, if you are not careful, you might be affected by anger.

Lust, hatred, jealousy pride, and such other unwholesome states, arising in the heart, spoil ones whole being. The original cause of all these defilements of the heart is unmindfulness which is based on ignorance. On the other hand, if a person tries to be attentive at every step of his life, let alone mindfulness in higher religious practices, such attentiveness would undoubtedly lead to great success. If a child studies his lesson, with every word he must be mindful. otherwise some very important instructions may escape his notice. It is then that he can understand and incorporate everything perfectly. On one occasion the Buddha said, "Sati sabbatthika." This means, "Mindfulness is advantageous in every activity." On another occasion he said, "All successful practice could be expressed in one word; that is appamada, which means, ‘"vigilance," or "mindfulness."

Generally the Buddha advised his disciples both monks and laymen, not to step beyond the boundary, and the boundary is mindfulness, which is to be developed in four ways, termed as four satipatthanas.

The four requisites necessary for to maintain himself or herself are: body, food and drink, a place to treatment. The Buddha advised his requisites mindfully. That is why nuns maintain silence when they use every living being a covering for the rest, and medical disciples to use these Buddhist monks and such requisites. When they don their robes, they should meditate: "I don this robe not to decorate the body or enhance my beauty, but just to cover my nakedness and keep it free from the effects of heat and cold and insects." Similarly, when they eat, it is with the thought, "I take this just to remove my hunger and thirst and to keep my health in order to live a pure, religious life&emdash;never for the sake of enjoyment or to gratify my greediness, When they sit or lie down, they must muse on the purpose of sitting or lying down, thus: "I use this seat or bed to give me rest, to protect me from the effects of wind and heat and insects. The purpose of giving refreshment to the body is to continue my religious life successfully, and never for the sake of enjoyment." And then, when they take some medicine, they have to be mindful of the purpose of taking medicine&emdash;that is, to remove ill health and to keep well. So, every moment, they have to be mindful.

In every activity we have to be mindful. Mindfulness applied to higher and higher practices will certainly give higher and higher results. When one keeps precepts, one should always be attentive that one does not break any rule. Thus, in observing precepts and in keeping vows, one must be ever mindful not to allow one’s thoughts to wander toward the objects of temptation. It is only when one is unmindful, that a rule or vow is broken.

Keeping precepts, or building good character, is the foundation for the development of higher virtues. And for the sake of his inner development, a person of good character must practice meditation.

There are two types of meditation practices, as taught by the Buddha. One practice leads to ecstatic trances, reducing the grossness of the mind step-by-step, inviting more and more calmness, peace, serenity, and purity to the heart and mind. The other kind of meditation, not only brings peace of mind, but also opens the mind’s eye to see perfectly the exact nature of oneself and others. In brief, it leads the aspirant to clear comprehension both the nature of the world and the nature of that which is beyond the world.

The first kind of meditation begins by fixing the mind on one point, which eventually leads it away from all tempting objects. There are forty objects of meditation, approved in the Buddhist system of meditation, one of which the expert meditation teacher chooses as suitable for the practitioner. For a beginner, the practice of fixing the attention on the spot where the breath touches the nostrils is recommended as being very fruitful. Starting with mindful attention on his breath, the aspirant has to rise in his practice, step-by-step, passing through the eight different grades of ecstatic trances. When he rises, at last, to the trance of extreme fineness of mind, wherein he feels his mind is neither conscious nor unconscious, he has come to the consummation of his concentration development. Throughout this practice, he must be mindful and attentive to the object on which his mind is fixed.

A person who has developed his mindfulness to such a level-still has not yet attained to full freedom from suffering. He has only suppressed all mental defilements and their consequences. As a result of this kind of inner development, he is said to be reborn after death into a higher and finer state of life. He may live in this blissful state for aeons of years, but would return to this gross plane of the world after the force of ecstasy (he has accumulated by means of his practice) is exhausted.

Now he has to practice the other line of meditation: the practice of vipassana. It is very easy for a person who has developed concentration and mindfulness to turn his channel to the practice of vipassana. Vipassana is the method of investigating the conditioned things of the world from various angles. It is the development of introspection.

The practitioner of this system must start with something conditioned. The most important and useful object of one’s search is oneself. The aspirant must first examine and mentally analyze his body. Any part of the body, he can examine and analyze how it has been formed and of what sort of things it consists. Applying his mindfulness at every step of this self-examination, the aspirant must analyze his entire body. Eventually he will realise that every part of his body is impermanent, subject to change, aging and disease and lacking any abiding substance. He will find that the entire body is just an aspect of nature, it is impersonal and does not belong to him. The body exists because of certain conditions and when these conditions ceases the body dies. This is the law of nature.

After analyzing the nature of his body, the aspirant should examine his mind&emdash;how thoughts, images and emotions arise and pass away, If he keenly examines his mind, he will find that all mental states are yet faster in their momentary change than gross material states. The mind is impermanent, is the cause of suffering and dissatisfaction, and it is impersonal, lacking any abiding substance. He will see that "me" and "mine" are only concepts created by his thinking process.

When the aspirant comes to the culmination of this practice, he will see the exact nature of the conditioned world. At this stage, he will also see its opposite side which is the Unconditioned, Unmade, the Real, and the Eternal. This is the end of his religious practice. At all these steps, mindfulness plays the prominent role. Without mindfulness, no success is to be expected.

Why Vesak is significant for the global society?

by Bhikkhu Horowpothane Sathindriya

Today, society is riddled with a multitude of religions, faiths, beliefs and cults, which the individuals have inherited as a birthright, or chosen according to their personal preferences, compatibility with their thinking or for offering succour to their needs.

History chronicles, that the dictates of these beliefs have driven man through the ages, either by deep religious fervour or blind faith. There is evidence of even self-sacrifice, being made, seeking a reward in this or the nether world - (heaven); in return.

Prince Siddhartha Gotama was born in India 2,625 years ago. With intuition gained in repeated cycles of birth in his journey through Samsara, he realised early in his youth, that, far beyond all the transient splendour and worldly pleasures in his princely life, there lay a state of release from suffering.

He had to find the answer to this vexing question, as to how he could stop this ongoing cycle of birth suffering and death.In his quest to unravel the truth he searched far and wide, seeking counsel from famous teachers, acclaimed for heir spirituality. Each attempt ended in an impasse. Realising the futility of such ventures, he set out on his own for six years in search of the truth, firstly through self-indulgence, failing which he resorted to self-mortification.

Finally, it dawned on him that these two extremes were hindrances to his progress and the only way open, was the Middle Path. The aspirant of the Buddha (Bodhisatta) preserved with gain determination to unmask the treasure latent in him viz. wisdom, concentration and morality and through these the four Noble Truths.The truth of the Dhamma, proclaimed by the Buddha, 2,600 years ago finds acquiescence with the advances in science. By virtue of this realism and rationality, Buddhism has found favour among the erudite and intelligentsia in the East and West.

Albert Einstein, the father of the modern science, once said, “In an age when science has advanced, the only doctrine, that science cannot contradict, is the teaching of the Gotama Buddha”. He also said that “A religion without science is lame and science without religion is blind.”It is impossible to condense of the Dhamma and its embellishments, which do not conflict with any philosophy or emotion into a short essay.